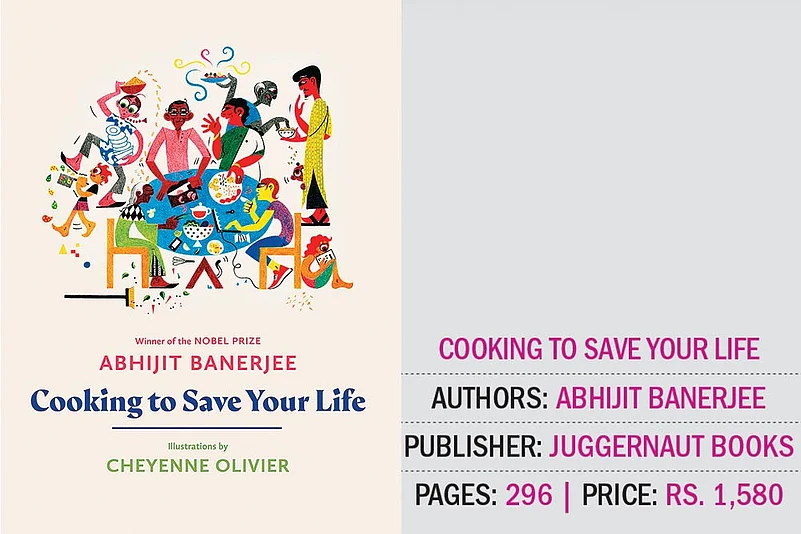

It is not everyday that a Nobel-winning economist writes a cookbook, so when Abhijit Banerjee does, you sit up and take notice.

Banerjee writes that he started cooking family dinners as a teenager and the hobby grew with age as his repertoire of recipes also widened across cuisines.

There’s something for every diner in this book: The vegetarian, the meat-eater, the vegan, the snack-eaters, the dessert lovers or those who restrict themselves to salads. But through it all Banerjee tries to demystify cooking, as he writes: “The goal here is to make delicious food with ease and confidence, to help liberate your inner gourmet cook from the weight of many cooking projects gone wrong”.

Here is an excerpt from the book:

I like my hors d’oeuvres to be exactly that, not the main meal by other means. Piquant or rich, and maybe a little surprising. A wake-up call for the eating mind as much as for the mouth. And less than ten minutes of work.

India is one country where this idea of hors d’oeuvres has never sunk in. The compulsion to be generous as a host is so strong that it is never okay to impose limits on what comes before the meal. It is always one more kind of kebab, or another dainty kachori stuffed with, say, fresh peas and bits of cauliflower, or some phuchhka.

All wonderful, but they keep coming, and I keep eating, distractedly, while trying to focus on the conversation. And then, sometime uncomfortably close to midnight, the host announces dinner. I am already full and half drunk. But the food is delicious, and I keep eating. The night does not pass lightly.

A meal is a story, sometimes a story that has lost its way. But always a story. The hors d’oeuvre is the preface. A good preface tantalizes, sets the tone, provides a slender window into the aspirations of the author. Anything more and it is too much.

A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy is one of the more important writings of Karl Marx, who is one of the most influential economists of all time. But almost no one reads it, because it has a lucidly written preface that presages almost everything that the book will say. People read the ‘Preface’ and feel that they are done, which is a pity since the ‘Contribution’ is probably a better way to get into Marx’s views than his famously turgid masterpiece, Das Kapital.

A central point in the ‘Preface’ is that economics rules. What Marx calls the relations of production, which is a fancy way to describe the way production is organized, more or less determines the shape our lives take. Everything else, culture, religion, institutions, is moulded to serve the basic economic relationship. Under capitalism, food is important, because it provides fuel to the workforce, but cooking is a distraction, at least from the point of view of a social scientist, except to the extent it is interesting to understand why the distractions are the way they are.

This spawned a long tradition of studying workers (especially workers in poor countries) as walking, talking machines that turn calories into work and work into commodities that get sold on the market. This focus on being productive means that poor people must always be on the lookout for more calories and better nutrition. The pleasure of eating, to say nothing of cooking, has no place in this description of the lives of the poor.

Fortunately, the poor refused to cooperate. As anybody who has ever spent time with actual poor people knows, eating something special is a source of great excitement for them (as it is for me). Every village, however poor, has its feast days and its special festal foods. Somewhere goats will be slaughtered, somewhere ceremonial coconuts cracked, perhaps fresh dates will be piled on special plates that come out once a year, maybe mothers will pop sweetened balls of rice into the mouths of their children.

And perhaps predictably, the non-poor adapt these celebrations to their own situations: my family in Kolkata, many, many generations away from farming, still celebrates the winter harvest. Rice, coconuts, date sugar, cane sugar, sweet potatoes, milk, sesame seeds and more, in various combinations, are turned into tables full of different delicious desserts, and those warned off eating too much sugar have to suffer the sight of them.

My selection of hors d’oeuvres is inspired in part by the marketplaces of the developing world where the less affluent will often go for their occasional excitement. Every other stall sells something sharp or sweet or spicy to eat. Dozens of families on their weekly or monthly day out crowd around, eating and laughing, jostling each other.

In Nairobi, it would be mutura, the fiery blood sausage that I (and all other foreigners) are forbidden to even try; in Lima, obviously Ceviche (pages 12–15), in Jakarta maybe Nasi Goreng, in Delhi, Fruit Chaat (page 10), in Kolkata, Street-Snack Potatoes (page 30), in Mumbai, perhaps Masala Peanuts (page 26).

It is probably no accident that these tend not to be especially nutritious. When life is hard enough as it is, these outings and that bite into something nice provide variety and relief and make it easier to go on. Cheap and nutritious is what they eat day in and day out; a little splurge on something else that excites the mouth while being inexpensive and fast is a natural choice.

With the right ingredients, piquant is easy to produce cheaply and quickly. High turnover is what keeps the food affordable—subtle tends to take time, attention or money.1 For me, piquant works well when the main meal is not eaten right away. The actual lunch or dinner can then start gentle, with soft flavours that build to something dense and complicated.

If time is short, maybe skip the hors d’ouevres or go for something either fat or umami rich (bluefish pâté, page 24, or marinated cheese, page 16) with a strong salad or a set of spicy vegetable dishes as the first course. But of course, that partly depends on the story you want to tell – I will tell you mine as we go.”

(This is an extract from Cooking To Save Your Life published by Juggernaut Books)

***

Bookmarked

Take a look at what’s new in the business section of Amazon’s book shelf

1. Price of the Modi Years

Aakar Patel (November 2021)

Columnist, author and political commentator Aakar Patel looks to break down India’s performance under Prime Minister Narendra Modi through facts and figures.

2. The Subtle Art of Intraday Trading

Indrazith Shantharaj (November 2021)

It is a deep dive into the world of intraday trading by offering techniques required to taste success in the exciting yet risky activity.

3. The Minimalist Entrepreneur: How Great Founders Do More with Less

Sahil Lavingia (November 2021)

Taking a cue from the author’s own journey, the book offers budding founders ways to figure how to build a thriving software-enabled business.

4. An Incomplete Life: The Autobiography

Vijaypat Singhania (October 2021)

The book offers a rare glimpse into the life of the erstwhile Chairman Emeritus of Raymond Group and how regret and heartbreak lace a life lived to the fullest.

5. The Almanack Of Naval Ravikant: A Guide to Wealth and Happiness

Eric Jorgenson (September 2021)

The book is a collection of entrepreneur, philosopher and investor Naval Ravikant’s 10 years worth of wisdom and experience, shared as a curation of his most insightful interviews and reflections.