We begin with the fact that the judges of the Supreme Court face a crushing case load. As we described in Chapter 1, the Court’s pursuit of being a ‘people’s court’ has led it to invite a massive flow of SLPs that it must sift through. The Court receives over 60,000 petitions per year. It devotes two days per week—Monday and Friday—to hearings on whether to admit or dismiss these petitions. And because it holds at least one hearing per petition, and sometimes more, before admitting or dismissing the petition, this means that on any given Monday or Friday, the Court holds around 1000 hearings.

The judges of the Supreme Court must somehow sort through this mountain of cases. To do this, it divides itself into benches of two judges to hear each petition, allowing it to hold many hearings in tandem throughout the day. And it holds incredibly compressed hearings. As we’ve noted, most hearings on SLPs last one minute and thirty-three seconds or less. In other words, in a typical case, the judges hear the law, facts and arguments relevant to the case for less than 100 seconds before they make their decision.

Yet, as our data shows, the initial hearing for an SLP is the most crucial hearing for a case seeking relief in the Supreme Court. A petition that makes it past this first step is nearly guaranteed a full hearing by the Court and a chance at winning the case in a final judgment. How can judges make such a momentous decision after a hearing that lasts less than two minutes?

The answer, of course, is that two minutes is simply not enough time to have an adequate hearing of the relevant facts, legal issues, case history and arguments by the petitioner. Yet every Monday and Friday, the Supreme Court makes admissions decisions on hundreds of cases on the basis of less than two minutes of hearing time. With so little time per case, the Supreme Court must make snap decisions, and one piece of information that it always has when making that decision is the identity of the lawyer making the argument.

Given these facts, it should be no surprise that senior advocates are so valuable to the Supreme Court. They represent familiarity, trust, experience and knowledge in a setting where hard facts, legal details and time are in short supply. A senior advocate arguing before two Supreme Court judges at an admissions hearing is likely going to have more experience in the Supreme Court than both of the judges combined. From day one on the Supreme Court until retirement day, a Supreme Court judge will see the same senior advocates again and again. Even if the bias is unconscious, it would only be natural for a judge to defer to a familiar face who has much more experience than

the judge has.

This deference is natural, but it is also a problem. The senior advocate has credibility due to experience and expertise but isn’t likely giving an objective assessment of the worthiness of the petition. The senior advocate is an advocate, who is highly paid to obtain a specific result from the Court. Further, the initial admissions hearing is not a balanced hearing, where both sides are heard. Usually, only the counsel for the petitioner is present.

Further, the power of the senior advocate is not available to all. With rates exceeding Rs 15 lakh for the most prominent senior advocates, this power is available only to the very rich. To be sure, many senior advocates offer their services at reduced rates or even free as a pro bono service to clients who are less wealthy, but this charity is exercised at the discretion of the senior advocate. In other words, the decision of who gains access to the Supreme Court is once again in the hands of the senior advocate.

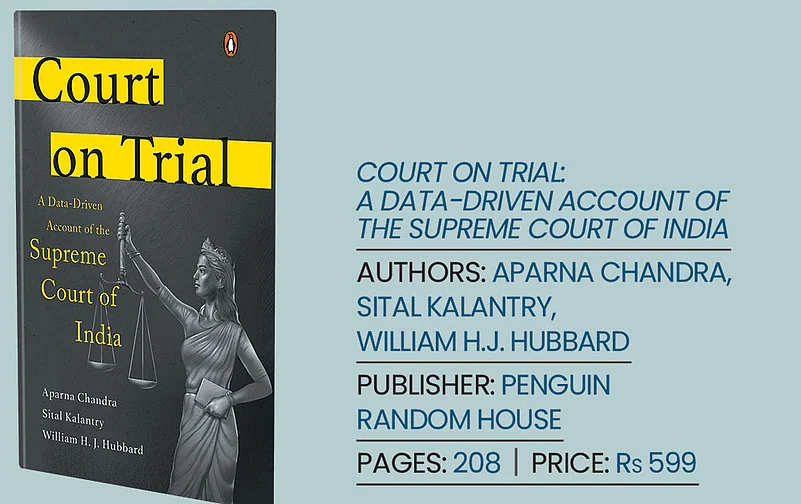

How Did the Supreme Court Get Here?

This is not a good state of affairs. As we have shown, there is little evidence that the power of senior advocates is about the valuable skills they could provide—giving the Court better legal rules and better cases. Instead, it seems that the Court’s preferential treatment of senior advocates is more about a bias towards familiar, respected individuals, regardless of the merits of the petitions. How did we get to this point? One explanation is the Court’s enormous docket of SLPs. The Court is desperate to sort through them, so the judges simply defer to senior advocates. Thus, we see the ‘face value’ of senior advocates—simply by showing up to the Supreme Court, they give their clients an advantage in getting admission to further hearings.

Importantly, the crushing load of petitions is partly due to the Court’s own policies and how lawyers have reacted to them. In this section, we show how three key groups have contributed to the extreme number of petitions:

***

Bookmarked

Take a look at what’s new in the business section of Amazon’s bookshelf

Back to Bharat

Nagaraja Prakasam (July 2023)

The book, through case studies, addresses the present dilemma of Indian entrepreneurs and consumers in terms of economic development and environmental threats as they look for sustainable alternatives in the areas of production and consumption.

World Upside Down

Sujan Chinoy (July 2023)

In his book, Chinoy attempts to provide a seamless narrative of emerging geopolitical challenges with his assessment of India’s outlook, responses and role in a rapidly evolving world order.

Play to Transform

Avinash Jhangiani (July 2023)

The author draws from real-life examples to show how play can be used as a catalyst for transformation and innovation. He argues that in the post-pandemic world, business leaders need to be more empathetic and agile than ever.

The Global Trade Paradigm

Arun Kumar (June 2023)

Global trade is key to peace and prosperity in the world. The author explores the ecosystem and the stresses it faces, basing his observations on his experience of over four decades.