Scroll, scroll, and scroll some more! God forbid if you stop scrolling as your eyes latch onto a dreamy deal. A shiny new trinket you’ve been eyeing for quite some time is on offer for just ₹1. Tap on the ad and it will take you down a rabbit hole all of us have become so familiar with.

The Dark Economics Behind ₹1 Flash Sales on E-Commerce, Food Delivery Platforms

Deep discounting tactics like ₹1 product offers are being widely used by e-commerce and quick commerce players to drive user acquisition and engagement. Platforms such as Meesho, Swiggy, Blinkit, and FirstCry use these psychological pricing strategies not just to boost click-through rates and cart sizes, but also to encourage first-time purchases and cross-selling

In just a few moments, you will have transitioned from mindlessly scrolling on your favourite social media platform to an e-commerce platform’s listing page, adding products to your cart because they’re on offer at lucrative prices.

Sample the case of Deergha Chadha, who was flicking through her Instagram feed on a lazy afternoon when she stumbled upon a mind-blowing deal: lipsticks, lip balms, and face powders from a premium brand, all available for only ₹1 each. But as soon as she added a lipstick that costs just ₹1 to her cart and proceeded to check out, the platform charged ₹199 for delivery charges. Finally, she ended up paying ₹200 for a low-cost lipstick.

"My experience in terms of product quality wasn't good. My cart size was one product per order because if we put more than that, the offer doesn't apply. Also, rupee 1 is just a clickbait, you've to pay the delivery charges much more than usual," she said.

What started with a one-rupee thrill quickly turned into a mini haul. Another online shopper, Tanni Mandal, faced the same issue. "Last year, I stumbled upon an offer it was one of those spin-the-wheel e-commerce deals...it sounded like a steal. It was a horrible experience. I never bought from that brand again, and I never will."

Big players, including the likes of Meesho, FirstCry, Swiggy, and Blinkit, among others are increasingly using single-digit price tactics to drive first-time purchases.

"During a recent ₹1 campaign on one of the e-commerce platforms, I ordered groceries and essentials worth ₹3,000. I first got 1 kg sugar for ₹1 after meeting a ₹500 cart value. Then, on reaching ₹2,500, I unlocked 1 litre of ghee for ₹1. I just kept on increasing my card size, to get the offer," Shweta Singh shares.

These are just a few examples—there are countless more out there. These dark pattern sales and marketing tactics—masked as deep discounts that offer premium products at throwaway prices—are commonly used by ecommerce, quick commerce and food delivery platforms to attract customers.

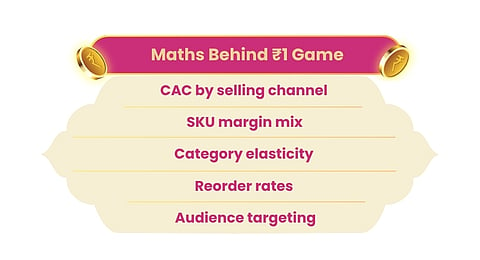

These tactics are not just marketing fluff anymore. They are usually a part of well-calculated moves leveraged by companies to drive user acquisition. It's called the economics of acquiring and retaining customers as the companies burn cash in marketing. As per industry experts, an ecommerce platform currently spends ₹350-500 as Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC) to generate a new order.

Not Just Bargain, But a Business Model

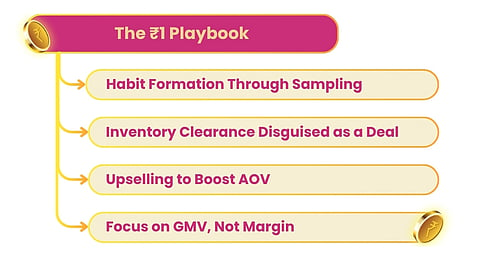

“When you are new to the business, you want users to try your product and get used to it. That’s where the ₹1 pricing comes in. For customers, ₹1 product is a low-risk way to experience the service. Even though it doesn’t make economic sense, it’s effective in forming habits,” says Preetam Jena, CMO and head of ecommerce of Fixderma, a homegrown skincare brand.

For example, in the early 2000s, Air Deccan offered flight tickets for as low as ₹1 in a market dominated by Kingfisher Airlines and Air India. At the time, the low-cost carrier just wanted people to make a shift from train journeys to flights. Apart from the one-rupee offer, the airline’s average ticket price was nearly 30% less than those of full-service carriers. However, Air Deccan ceased operations in April 2020 due to the disruption caused by Covid-19 pandemic and the subsequent lockdown.

Coming back to deep discounts, such campaigns continue until a start-up or company acquires a set number of users who become regular customers. In short, the main purpose of selling a product for ₹1 means “sampling”, according to Nikita Aggarwal, brand strategist at founder’s office of NxtWave.

Apart from the initial user acquisition target, Jena explained that ecommerce players also focus on aggressive discounting to clear “dead” or “near-expiry” inventory. He added that the third case would be “cross-sell or upsell strategy”. Under this, a seller encourages a customer to purchase more or add complementary items that increase the overall purchase value.

To understand this better, let’s take an example of ordering a burger from Zomato. On the check out window, the app shows options like “upgrade to meal combo for ₹89 extra”, “add fries and coke”, “add extra chips”, and so on.

“It’s a technique to boost Average Order Value (AOV) and improve Customer Lifetime Value (CLV)—key metrics for any ecommerce, food delivery or quick commerce business,” Jena adds.

The fourth side of this trend lies in investor-driven start-ups that usually prioritise Gross Merchandise Value (GMV) as a “growth signal”. GMV is calculated at MRP before discounts.

“Such brands often present strong top-line figures to investors—even even if their actual contribution margins, calculated from net sales, tell a different story. They just focus on reducing the pressure to showcase scale. Contribution margins shrink, but optics look great for the next funding round,” he asserts.

Amid the push for deep discounting, the question arises: What’s behind this single-digit product selling strategy? Does it bring a huge number of loyal customers in long run? Are start-ups able to convert the leads into profitability? Industry players and some real examples reveal the true picture.

All Hype, Low Returns

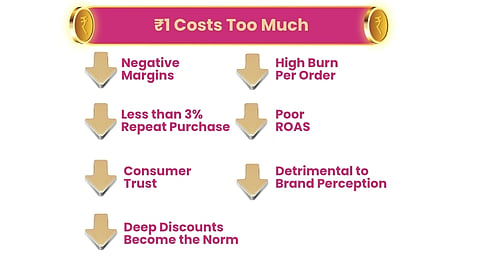

Some consumer brands have seen short-term gains from ₹1 marketing campaigns, like higher app installs or increased footfall till the time the offer is live. However, most such tactics do not result in long-term value, explains Ashutosh Kumar Jha, General Partner at Expert Dojo.

He further notes that some D2C personal care brands observed less than 3% repeat purchases after sample giveaways. On top of that, they also report negative margins due to logistic costs. Jha stated that these marketing campaigns run without “a follow up step towards revenue generation” result in poor ROI (return on investment).

Sirona founder Deep Bajaj also echoes similar sentiments, saying the conversion rates post-trial, however, tend to be less than10% unless reinforced by strong brand storytelling or retargeting campaigns.

According to him, these marketing tactics are “rarely” sustainable because they lead to high burn per order, poor ROAS (return on ad spend), and low margin recovery over the lifecycle unless customer retention is very high; for example, for players like Nykaa, and Amazon, among other big players. In short, these offers lead to “unsustainable” customer acquisition model.

On the buyers’ side, such campaigns also smell of “deception” because hidden charges like “inflated shipping fees” are bound to erode customer trust, says Amit Tilekar, chief marketing officer of Wonderchef. He believes that there should be regulatory guidelines around misleading pricing and platforms should clearly communicate the terms— including what’s covered and what’s not.

It also shifts consumer buying behaviour as people begin to expect freebies and heavily discounted offers as the norm, to make a purchase online. The most relatable example is of Nykaa’s Pink Friday sale. The beauty and fashion ecommerce firm recorded 75% growth in GMV and a 12-fold jump in revenue on day 1 of its Pink Friday sale in 2022 because Nykaa offers heavy discounts every Friday.

Hence, people wait for the day to shop on Nykaa. The strategy has worked in the past for Nykaa because its customer retention rate was more than 70% in FY22.

In addition, it can also negatively impact the brand’s perception. “Consumers just buy and use the product at Re 1 and its’ a steal deal than a sampler. Brand value is low unless some sort of experience or value is provided before giving the product. It is detrimental for the brand image,” says Aggarwal.

Despite all these downsides, there are some players who have cracked the code.

Some Got It Right, Some Paid the Price

Ankita Vashishtha, founder and managing partner at Arise Ventures shares a case study from one of their consumer portfolio companies that ran a ₹1 campaign for an FMCG product. Its distribution strategy was limited to selected urban pin codes, and the offer was available for a short duration only. And their precision paid off.

The brand saw a 27% conversion rate to paid repeat purchases within the first 30 days after the offer was closed. Even more than 40% of those converted customers transitioned to subscription or bundle customers within next three months, she added.

Another example that suits this trend well is FirstCry, which ran a campaign called “Free at 3”. Under this, it used to offer certain products for free, but only for 10 minutes at 3 pm. “It worked well for Brainbees Solution Limited to boost engagement and conversions,” said Jena.

“Dyson also does really well in Southeast Asia, specifically in Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand. They have big shopping events like 9.9, 10.10, and 11.11, which is similar to Big Billion Days in India. Dyson is a premium brand, but during those dates, sales spike,” he notes.

Aggarwal also shared an example from her time at [Descriptor] Happilo, where the company ran a targeted sampling for its dry fruit bar in collaboration with ecommerce and quick commerce platforms. A special ₹10 sampler pack was created to offer it as an add-on above a certain cart value. From this campaign, over 40% of users who tried the bar went on to make a repeat purchase. For the remaining 60%, the brand rolled out a second-level trial—a 12-piece pack with a 1+1 offer, which drove another 30% conversion.

VC firm Expert Dojo, too, highlighted the success story from one of its portfolio companies. One company used a Re 1 campaign to drive 100,000 trials of a premium feature. About 25% of the users completed onboarding, and 8% converted to a paid subscription at Rs 1,600 monthly.

“This worked because the campaign was linked to a well-structured product journey with targeted nudges and usage-based prompts. The campaign itself was not the growth engine; it simply opened the door. Success came from optimising each subsequent user touchpoint,” Jha explained.

But not everyone succeeds. For example, food delivery platform Foodpanda—which ran ₹1 and ₹9 deals for a long time—had to eventually shut shop in India. The content-to-commerce platform, Good Glamm Group, also tried the ₹1 strategy; today, their situation isn’t great either.

The ₹1 Dilemma

Ultra-low pricing campaigns like ₹1 offers can only delivery short-term spikes in installs and trials, but most experts agree that they “rarely” lead to sustainable growth unless supported by strong retention game. “Without better service and brand affinity, it only becomes a race to the bottom,” say experts.

It can drag CAC down from ₹500–₹800 down to nearly zero, but again, the real gain lies in long-term value. Jena states that the campaigns also increase the click-through rates. Typically, this rate is around 1%. But if the add says the product costs ₹1, the likelihood of someone clicking on it increases significantly—maybe even to 2%. Hence, it drives the attention.

They advise brands not to rely on deep discounting without a strong retention strategy. The model only works if they are confident of making money from second, third, or fourth purchases. Unless at least 5-10% of the users convert post-trial, such campaigns just dilute the long-term unit economics for the company.

In a nutshell, the strategy can either be a scalable hack or a signal of negative fundamentals for the start-up trying to make it big.