At the confluence of two seemingly isolated events, separated by several oceans, lies the story of a sea change, both in reality and perception.

Drones, Diplomacy and Dominance—India’s Economic Ascent Needs to Outgrow its Pacifist Past

India must flex its military muscle and defend hard-earned economic gains of over seven decades

In London, India signed a historic trade pact on its own terms with the United Kingdom (UK), its erstwhile imperial master, and in Pakistan, through Operation Sindoor, it destroyed nine hubs of Islamist terror, sponsored by the non-state actors of a rogue state.

India’s telling retaliation—24 surgical missile strikes in 25 minutes on May 7—coming close on the heels of the trade deal, drove home a reality: the country’s capability and resolve to hunt down terrorists wherever they might be, with precise, risk-calibrated retaliation. A capability it first demonstrated in 2016, in response to the Uri outrage.

The juxtaposition couldn’t be more striking: a country striking deals by day and targets by night. These events illustrate a powerful new alignment between diplomacy and defence in India's external strategy.

Strategists see this as a doctrinal shift. No longer merely restrained or passive in the face of provocation, India is articulating a security framework grounded in swift retaliation and economic independence. "As global power realigns, military strength is no longer just a deterrent; it's a diplomatic tool for demonstrating economic superiority," observes Major General (retd) Rajan Kochhar. "Through this very ability to neutralise threats while negotiating from a position of strength, we have now sent a message to the world, especially to our adversaries."

India’s economic growth story has gained international recognition. Now a $4trn economy with projections to reach $10trn by 2035, the country is seen as a key node in the global supply chain and a significant voice in multilateral forums. A testament to this growing stature is the recently concluded trade agreement with the UK, having overcome key hurdles related to mobility of professionals, rules of origin and market access.

For India, the gains are substantial: the complete elimination of British tariffs on 99% of Indian exports provides a decisive boost to industries ranging from textiles to pharmaceuticals to digital services.

This comes at a time when global trade alliances are under strain and the United States (US)—under President Donald Trump—has offered India little stability on the trade front, issuing contradictory and shifting policy statements that make long-term planning difficult. Against that backdrop, the UK deal signals not only access to a stable Western market but also reinforces India’s image as a confident negotiator and economic power that can extract favourable terms even amid a surge of global protectionism.

But there is a striking pattern to what India achieved in the month of May. While the world lauded its economic ambition—eager for access to its vast market—there was notable silence when India came under attack. During the tense hours of Operation Sindoor, as Pakistan escalated conflict by targeting India’s military infrastructure with drones and missiles, few international partners stepped forward in support. Instead, in a move that drew sharp criticism from India, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) approved the immediate disbursement of around $1bn to Pakistan. Additionally, the IMF sanctioned a fresh $1.4bn loan to Pakistan under its climate resilience fund even as the conflict unfolded—highlighting India’s continued difficulty in isolating a rogue state diplomatically.

Just when India had a window to cripple Pakistan’s strike capacity—its air defences neutralised and key radar destroyed—US President Donald Trump intervened unilaterally. In a social-media post, he declared that he had brokered a ceasefire between the two nations, effectively halting India's momentum and signalling a direct, unsolicited intrusion into India’s strategic calculus.

The Indian government swiftly denied any US role, but on the world stage, the voice of the American president drowned out India’s diplomatic rebuttal.

This episode underlined a hard truth: while the world celebrates India’s economy, it remains uncomfortable with India’s assertion of hard power. And it affirmed something India has long suspected—that in matters of security, it may well stand alone.

“We should understand that it is not in the interest of the Americans, French, Russians or China that India comes up as a self-reliant military force,” says Ravi Kumar Gupta, scientist and former director with Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO). “Every rupee spent on imports acts as a catalyst for economic growth and social development by creating jobs and accelerating industrial activities in countries from where we import. For decades, therefore, Bharat has been funding growth and development in such countries at the cost of our own security and development.”

Alone at the Table

The strategic landscape surrounding India is tightening, with adversaries becoming more assertive and allies more ambiguous. To the west, Pakistan continues to provide sanctuary to terrorist groups while wielding its nuclear arsenal as a shield. To the north, China presses its territorial claims along the Line of Actual Control, even as it expands its maritime presence in the Indian Ocean.

To the east, the removal of the pro-India Sheikh Hasina government in Bangladesh has injected fresh uncertainty. A new regime, less aligned with Indian interests and increasingly supported by Beijing, raises the risk of a hostile eastern flank. Just days before the Sindoor strike, Dhaka’s former border force director general issued a thinly veiled warning: should India attack Pakistan, it could risk losing the Northeast.

This shifting contour of geopolitics is symptomatic of a larger strategic manoeuvre at play—one orchestrated by China. With its vision of regional hegemony increasingly threatened by India's economic rise, Beijing has doubled down on a containment strategy using Pakistan and Bangladesh as proxies. From supplying Pakistan with armed drones and advanced missile systems to reinforcing its naval presence in Gwadar and Karachi, China has entrenched itself as Islamabad’s primary benefactor.

Recent reports also confirm that Bangladesh, under the new regime, is in talks to procure the J-10C fighter aircraft from China—the same aircraft type deployed by Pakistan during its show of force in retaliation to Operation Sindoor.

“Beijing cannot strike India without risking economic repercussions, cannot embrace it because it still shares deeply fraught relations with it and cannot ignore it as India gains traction in boardrooms and policy circles. But at the end of the day, the story will remain the same: it will continue to pursue its longstanding security alliance with Islamabad,” says Michael Kugelman, a Washington, DC-based South Asia analyst.

Economic Infrastructure at Stake

What makes the encirclement of India more dangerous is its direct proximity to India’s most valuable economic assets. From the world’s largest petroleum refinery in Jamnagar to the solar parks of Rajasthan, and the semiconductor hub emerging in Dholera—India’s infrastructure backbone is now within striking range of adversaries on multiple fronts. In a war scenario, these regions would be exposed to missile strikes, drone attacks or sabotage, threatening not just energy security but economic stability.

Key ports like Kandla and Paradip, along with industrial corridors in Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, are similarly vulnerable to disruptions. China’s growing naval assertiveness in the Indian Ocean and the Indo-Pacific, paired with its influence in regional ports through the String of Pearls strategy, increases the strategic pressure. With assets so close to the line of fire, India faces a stark reality: its economic rise is intertwined with its ability to secure these vital nodes from enemy encroachment or disruption.

“Increasingly, instead of the Himalayas, the Indian Ocean has become the real frontier for India. And India currently worries that China may already be deep inside it. As India ramps up its southern naval posture and maritime surveillance, it is clear that safeguarding prosperity will depend as much on diplomacy as on defending its shores and expanding its fleets,” says Kugelman.

Cyber vulnerabilities amplify this exposure. Financial systems, power grids and defence networks are increasingly digital. With China's rapid advances in AI, quantum computing and cyber warfare, India’s technological gap could become a national security risk.

The World Economic Forum's Global Risks Report 2025 identifies "state-based armed conflict" as the year’s most disruptive threat—likely to spark cascading crises across global supply chains. Similarly, the Allianz Risk Barometer 2025 ranks war, terrorism and political violence as the top risks to global business continuity and growth.

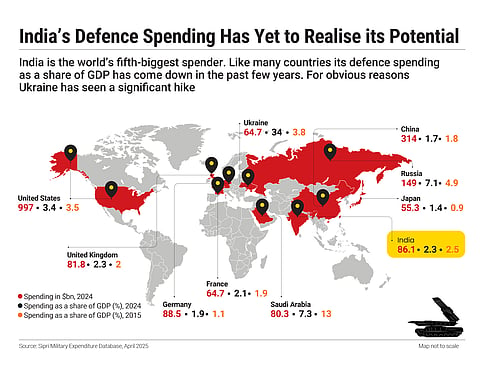

These fears reflect an increasingly volatile world, with conflicts stretching across a wide arc—from Ukraine and West Asia to the South China Sea and the Indian subcontinent. The cumulative effect has been a recalibration of investor priorities. Geopolitical risk is no longer an abstract threat, but a decisive factor in capital allocation. Consequently, global military spending in 2024 hit an all-time high, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (Sipri), as nations race to reinforce the connection between national security and economic resilience.

India’s strategic challenge is further complicated by the absence of hard security guarantees from the very platforms meant to counterbalance Chinese aggression. The Quad, though symbolically powerful, is operationally limited, with no shared defence commitments. Nato, meanwhile, remains Euro-Atlantic focused; its utility in Indo-Pacific scenarios is limited by geography and mandate. This strategic vacuum makes India’s posture more precarious, as it is expected to act as a bulwark against China without the backup extended to Western allies.

In this environment, India’s lack of a firm security alliance and its exposure to cross-border threats could place it at a disadvantage—not only in war scenarios but in the global contest for investments and strategic relevance.

“In a world where power equations are increasingly being shaped by coercion rather than consensus, India’s geography leaves it no room for complacency. India’s biggest challenge remains the one closest to home. In the South Asia region with increasingly unpredictable neighbours and a deep Chinese footprint, India’s security calculus demands a forward military posture that matches its economic ambitions,” says Kugelman.

Akash is Not the Limit

In the thick of the Sindoor conflict, India’s home-grown weapon systems, led by the Akash surface-to-air missiles, hit all the right targets—an emphatic demonstration of their capabilities for the over $600bn global military market, estimated by a Sipri report. More significantly, it was a dramatic illustration of how far the country has come since 2015, when the defence sector was brought under the Make-in-India fold, long seen as the toughest frontier for self-reliance. The introduction of Positive Indigenisation Lists (PIL) has since removed over 500 items from the country’s roster of importable hardware, ranging from weapons and sensors to ammunition.

General (retd) Ved Prakash Malik, former Chief of Army Staff who led India’s battle in the Kargil War, says, “Self-reliance in defence isn’t just an aspiration—it’s a necessity. It is about ensuring that when the need arises, the nation can respond swiftly, decisively and on its own terms, with the all-important surprise element.”

India’s strategic doctrine now hinges on the logic of autonomy: build what you can, and import only when necessary—and that too with full safeguards and technology tie-ins. The Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft (AMCA) programme captures this mindset well. Conceived as a fifth-generation stealth fighter with room for sixth-generation capabilities in future variants, AMCA exemplifies India’s long-term commitments to self-reliance.

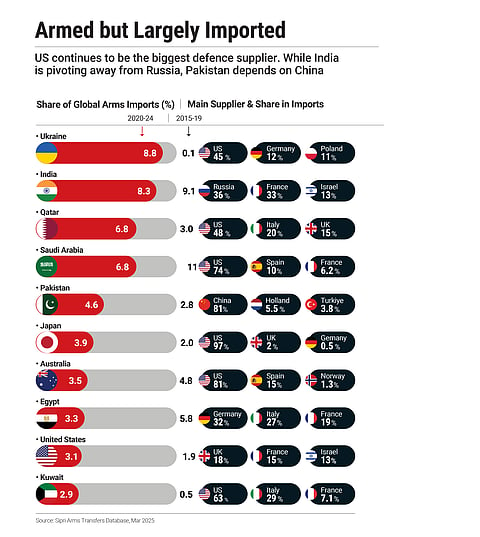

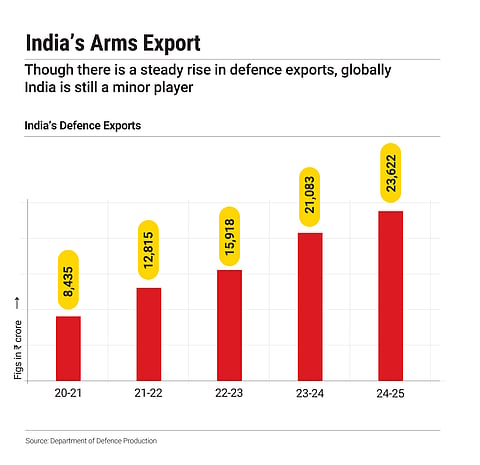

For decades, India has ranked among the world’s top arms importers. Between 2015 and 2019, it accounted for 9.1% of global arms imports, a figure that has since declined slightly to 8.3% for the 2020–24 period, according to Sipri. Its principal suppliers remain Russia, France and Israel. Yet India still trails only Ukraine—an outlier due to its ongoing war with Russia. The real transformation, however, is visible on the export front: defence exports have surged from ₹1,522 crore in 2016–17 to ₹23,622 crore in 2024–25, signalling a major shift in India’s global defence footprint.

Despite this growth however, India does not feature among the top 25 arms exporters in Sipri’s Arms Transfers Database, with its share in global arms exports still below 0.3%. This is partly because India’s exports are concentrated in low-value platforms and spare parts, rather than big-ticket systems that dominate global arms trade.

"India’s demonstration of its indigenous systems in the recent conflict has shown that it always had the capability to be a defence manufacturer. But the journey is far from complete. Major programmes are bogged down in delays because the procurement bureaucracy remains slow and risk-averse; state-run manufacturers still dominate a sector that needs the agility of private players,” says DRDO’s Gupta.

This supposed turnaround is not just about military pride. It’s about building a robust military-industrial complex that can create jobs, stimulate high-tech R&D, attract private capital and drive long-term economic growth. Some experts estimate that a mature domestic defence manufacturing sector is essential to increase the share of manufacturing in India’s GDP, which remains stagnant around 15%. And this drive towards indigenous defence production is vital also because of how lopsided the global arms market remains. A handful of countries—the US, China, Russia, the EU and the UK—control a near-monopoly over high-end military exports. Together, they game the global arms market, dictating not just prices but terms, dependencies and geopolitical leverage.

Export clients rarely receive cutting-edge systems. Take the F-22 Raptor for example, the world’s most advanced stealth fighter, which the US does not sell even to its closest allies. These technologies are preserved for national use—not only for tactical superiority but also for the decisive advantage of surprise.

Meanwhile, clients like India are offered legacy platforms repackaged in updated variants and sold widely—including to potential adversaries. These deals often come with strings: limits on upgrades, restricted spare part supplies and end-user conditions that erode operational autonomy.

"Exported platforms are almost never the topline. Countries will try to downgrade your defence by selling you oversold and dated platforms. The F-16 developed in 1970s, for example, has been sold to over two dozen countries, including our adversaries,” notes Gupta.

Until India develops its own Raptors, a hybrid strategy may still be essential. As Gen Malik recommends, India must plug short-term gaps with high-grade imports—such as F-35s or Rafales—but only if they come with India-specific enhancements, full transfer of technology and absolute guarantees of operational freedom.

The Future War

Make in India in defence is not just about economics. It is about sovereignty, resilience and projecting power in a world where security cannot be outsourced—and deterrence must be domestically manufactured.

Future wars will be fought less on the battlefield and more across networks, satellites and code. As Maj Gen (retd) Kochhar says, “The next generation of warfare is going to be in space.” Control of orbits and data pipelines is emerging as the decisive edge in modern warfare.

India has taken early steps—investing in space-based intelligence, anti-satellite capabilities and indigenous drones. But much of this remains fragmented and underfunded.

Public–private partnerships are critical to unlocking India's defence potential. Despite having a world-class tech talent pool, the sector is held back by entrenched red tape, bureaucratic inertia and outdated vendor policies. PSUs, with limited appetite for risk, further stifle innovation.

A case in point is the P-75 submarine project—initially supposed to be completed by 2017 but delayed due to issues ranging from structural inefficiencies to institutional ad hocism. Its follow-up P-75I is expected to meet with similar delays. But while India grapples with procedural delays, Pakistan is moving faster. This year, it obtained the second of the eight advanced Hangor-class submarines promised by China, signalling deepening military ties between the two.

“The biggest impediment in India is bureaucracy. Excessive regulations strangle progress, even as the government claims to push deregulation and ease of doing business,” says Maj Gen (retd) Kochhar. “If we don’t change our approach, by 2047 we’ll still be stuck where we are today. Nothing much will move. Because your defence ecosystem doesn’t exist in isolation—it flows from your industrial ecosystem.”

A similar problem afflicts India’s air defence. The most glaring gap is the acute deficit in the Indian Air Force’s squadron strength. Against the minimum requirement—in a two-front war scenario—of 42 squadrons (each comprising 16–18 aircraft), India currently fields just 31. This shortfall has been compounded by the slow pace of the Tejas Mk1A induction and the decommissioning of the ageing MiG-21s. Without urgent action, the IAF risks being underprepared in any high-intensity conflict.

Jayant Damodar Patil, the head of Larsen & Toubro's (L&T) aerospace and defence division, recently proposed the development of a fully indigenous 110 kilonewton (kN) thrust jet engine for India's fighter aircraft. This could involve major private players like Mahindra Aerospace, Tata Advanced Systems and Godrej Aerospace pooling their respective expertise and resources. "If the government backs merit over L1 [lowest bidders], then a pool of talent will be brought together,” Patil told the media.

Defend or Develop?

Given India’s Viksit Bharat objective of becoming a $30–35trn economy by 2047, the case for a deterrent military power has never been stronger. For, as Gen Malik notes, “An economy growing at an unprecedented rate would have exponentially more to lose and to defend.” But how? Leave alone the US, even to match the Chinese levels of deterrence, India would have to spend around 8–9% of its GDP annually through more than two decades—given its staggering socioeconomic challenges, this proposition is delusional.

This tension is at the centre of an increasingly vocal national debate. One side argues that India cannot afford to divert scarce resources to military expansion when over a tenth of its population still lives in multidimensional poverty. They contend that roads, schools, hospitals and green energy should be the real battlegrounds for funding. In a developing country, they ask, what good is a fighter jet when millions still lack drinking water?

The counterargument is anchored in realism: without robust defence, there is no economy to protect. A vulnerable India is an unattractive India—whether to investors or its own citizens. Every asset built, every industrial corridor laid down, every export deal signed is exposed to the possibility of disruption if India remains militarily underprepared. As one strategist puts it, “India doesn’t have the luxury to choose between guns and bread—it needs both or it will lose both”, referring to the trade-off between defence and domestic needs.

“India has long been perceived as a soft nation, unlike, say, Israel,” says Maj Gen (retd) Kochhar. “If you go back into history, to the ancient Indus Valley Civilisation, you’ll see why the British were able to rule over us—it was because of our passive strategic culture.”

But the debate is further complicated by India’s internal defence structure. With over 1.4mn active military personnel, India maintains one of the world’s largest standing armies—a force structure that some experts argue is disproportionate to modern threat scenarios. Many of these personnel may never be operationally required even in a three-front war.

To address this imbalance, the government has introduced the Agnipath scheme, aimed at modernising the military recruitment process and reducing the long-term pension and salary burden. The initiative is designed to create a leaner, younger force with short-term contractual service, allowing the state to redirect resources towards advanced technologies and strategic infrastructure.

However, the transition has been met with resistance from various quarters, including veterans' groups and political opponents, who argue that it undermines job security and devalues military service.

This creates a structural dilemma. The current government, despite acknowledging the need for a shift towards high-tech defence capabilities, is unlikely to pursue radical reforms that reduce headcount or reallocate budgetary priority away from personnel and towards technology. Any such move risks triggering political backlash, especially from the opposition, which may frame it as anti-jawan or anti-poor. And so, the status quo persists.

India sets aside around 2% of its GDP for defence, slightly more than China’s 1.6%, which may seem adequate at first glance. But in absolute terms, according to Sipri, China’s defence budget is projected at $314bn, nearly four times that of India’s. “In the next few years, India should aim to spend at least 2.5% for defence, and be willing to increase to 3% or more if required,” says Sachchidanand Shukla, group chief economist, L&T.

“It is a minimum that we must and can manage to spend consistently within our fiscal limitations and without sacrificing other key needs. This will help us have the necessary deterrence capability in our unique and hostile neighbourhood while being cognisant of our multidimensional growth needs for becoming Viksit or a developed nation,” Shukla adds.

The problem, however, cuts even deeper. Of the ₹6.81 lakh crore allocated in the 2025–26 defence budget, more than half is tied up in salaries, pensions and operational expenses. That leaves just ₹1.9 lakh crore for high-priority capital expenses to fill critical gaps in its war machinery.

And so, the question remains: How does India bridge the deterrence gap with countries like China without compromising on its compelling social development imperatives?

One possible solution gaining traction among defence economists is the introduction of a dedicated defence cess—a targeted levy that could boost India’s capital defence budget without cutting into social-sector spends. Concerns that it might provoke an arms race are increasingly seen as outdated, given that South Asia is already deep into a cycle of military modernisation.

China is expanding rapidly, Pakistan is augmenting its strike and surveillance capabilities with Chinese help, and Bangladesh too is investing in air and naval upgrades. India’s restraint, therefore, is doing little to prevent escalation—it is merely leaving the country exposed and underprepared.

“Now India should invest more in technology sophistication for defence and for war, so that we will have safeguard and we will be protected against any disgraceful behaviour by any of our neighbours or anybody else,” says TV Mohandas Pai, chairman, Aarin Capital. “I think Agniveer was a step in the right place to reduce the money that we spend on troops, because we’ll have a younger army.”

The answer is to stretch the military budget to the extent possible and, more importantly, to move the armed forces gradually towards a new paradigm of deterrence—driven not so much by tanks and artillery as by advanced next-gen platforms and cyber capabilities. Says Pai, “The Indian economy is on a tear—doubling to $4trn in just a decade and targeting $10trn by 2035. Securing such a large and prosperous economy will demand a robust, technologically advanced security framework.”

Future wars are likely to be increasingly fought with bots, not boots on the ground, and dominating such battlefields will depend more on data, drones and AI than on prohibitively expensive next-generation military hardware. “This scenario gives India the opportunity to maximise the bang out of every buck it spends on its defence and focus on right-sizing its armed forces,” says Gen Malik.

To resolve this impasse between the needs of the poor and the imperatives of power, India must embrace a new ethos of dual ambition. It must pursue growth with grit and security with subtlety.

After gaining independence, India embraced the doctrine of non-alignment to avoid being drawn into global conflicts. But that strategic restraint came at a cost—India lost significant parts of Kashmir to Pakistan and China, a consequence of choosing diplomatic distance over decisive defence at a time when its territorial integrity was most vulnerable. But that strategy belonged to an India still finding its feet on the world stage.

Today, more than seven decades later, India stands on the threshold of becoming a global power. It cannot afford to be found incapable of defending what it has built with the sweat and blood of its people. India must be prepared to defend itself—in the face of hostility from all quarters. As a nation, we must be willing to stand for what is ours.