For someone so inextricably linked to the film business, Javier Sotomayor manages to catch just three movies each month. In fact, the last one he watched was the Leonardo DiCaprio-starrer The Revenant early March at his 14-screen megaplex in Thane, near suburban Mumbai. Most of the films he does watch are on DVD, that too when he gets a breather from work. After all, the 44-year-old is busy trying to take his company Cinépolis India from 226 screens currently to 400 by next year. Headquartered at Morelia city in Mexico, the global megaplex player appointed Sotomayor as its India MD in 2013. With its acquisition of Essel Group’s 83-screen strong Fun Cinemas multiplex chain for Rs.550 crore in January last year, Cinépolis today is the fourth largest player in India’s growing film exhibition industry. This buyout also gave Cinépolis a foothold in the key Delhi market and a presence in smaller centres such as Ambala, Coimbatore, Dibrugarh and Ranchi.

“Our four-screen property in Delhi’s Unity Mall, eight-screen one in Pune and five-screen multiplex in Bengaluru will all be ready in a month or two. By the middle of next year, another 80 screens across 12 cities will be added, taking our total to 306. These are properties where the interiors are still under construction, but the work is under control,” says Devang Sampat, head, strategic initiatives, Cinépolis. According to Sampat, responsibility for newer projects — like the one in Chennai, where a deal has just been signed — has been left to the respective mall developers. Among the new properties are ten screens in Hyderabad, four to six in Guwahati, four in Kolkata, eight to 10 in Ghaziabad and 10 in Mohali. “We will also look at acquisitions during this period of expansion. That being said, it is more important for us to zero in on the right property and location instead of just chasing numbers,” Sotomayor explains.

Globally, Cinépolis is known for its megaplexes and the brand holds a position of prominence in much of Mexico and Latin America, with its 4,500 screens making it the fourth largest player worldwide. A megaplex in Sotomayor’s lexicon means a movie theatre boasting of at least 10 screens and so far, he has achieved that at three locations — Thane, Pune and Kochi, which together account for 40 screens. At a 12- or 15-screen megaplex, audiences can choose from at least three films over any half-hour period. “This way, people at a shopping centre could time their film outing; this was the game-changer for us. We also focused on the food offerings to add to the overall experience,” explains Sotomayor. He hopes to set up at least 15 more megaplexes in the country once the company is through with its expansion plans. But by any stretch of imagination, India is a completely different ball game from the markets Cinépolis operates in, and Sotomayor is acutely aware of this. Not only is India a large multilingual market, there is a serious space crunch since no new mall projects are coming up. The sheer number of competitors in the game complicates things further.

Mission impossible

In 2006, the top brass at Cinépolis — which means the city of cinema — sat down for a strategic meeting in Mexico with a clear objective. After successfully replicating the brand’s megaplex model in smaller countries such as Guatemala, Costa Rica, Peru and Panama, it was time to look for newer horizons; the management zeroed in on India, Brazil and Chile. The approach so far was to simply replicate the megaplex model. “It was a strategy we knew well, but one that was going to be very difficult to execute in India,” says Sotomayor, who has been with the company since 2002. The hitch was that mall developers were not willing to give Cinépolis the kind of space it wanted. For instance, a screen with about 200 seats needs a carpet area of 5,000 sq ft. A 10-screen megaplex meant that mall owners would have to lease out a significant chunk of space, a scenario that made them uncomfortable. “A decade ago, multiplexes paid negligible rentals, and mall owners naturally gave anchor tenancy to people who could pay more,” says Sotomayor. Even by the most conservative estimates, other running formats such as supermarkets, apparel stores and luxury stores were paying at least twice as much as multiplexes. “Obviously, they did not see value in cinema; it was more of a necessary evil,” he adds.

UB Venkatesh, owner of the Royal Meenakshi mall in Bengaluru, admits that he was initially nervous about signing a seven-screen deal with Cinépolis in 2009. “It was a new company with no presence in south India and it wanted 60,000 sq ft, which was 10% of the total mall area,” he recalls. Venkatesh decided to back the company after being impressed with its technology and international pedigree. “While we do have tenants such as Shoppers Stop and Croma, it is only entertainment and food that drive footfalls. With a smaller multiplex, that exercise would have been very difficult,” he explains. But the folks at Cinépolis had to work quite hard to convince Venkatesh to give them more than what was on offer. “Initially, the mall owners were willing to give us space only for four screens, before settling for seven. Even at the now-shut Neptune Mall in central Mumbai, we had to convince the developers to give us six screens instead of the four on offer,” says Sampat. Fortunately, Cinépolis includes a 25-year lock-in clause in its contract with developers, which saved it the blushes after Neptune’s closure. “Builder defaults are covered under our penalty clause, with the developers having to compensate us on account of loss of profit; we are legally protected in situations like these. But we are hopeful that the mall will reopen and that we can get back to business,” says Sampat.

Mall owners on their part are fast realising that watching movies at theatres has become the preferred entertainment option for families in India and that consumers are willing to pay more for a good movie experience, leading them to choose multiplexes (with average ticket prices of Rs.175-200) over single screens (average ticket price of Rs.60). Of the 8,000 screens in India, multiplexes account for only one-fourth but bring in more than half the industry revenue. Most multiplex owners have a revenue share agreement with mall owners, which usually averages around 17% of net ticket revenue. According to Rajneesh Mahajan, executive director, Inorbit Malls, it is quite normal for multiplexes today to occupy 9-11% of the gross leasable area in malls compared with 7-8% a few years ago. His company’s Vadodara mall houses six of Cinépolis’ screens. “A multiplex adds to the whole mall experience and positively affects F&B, entertainment and other shopping categories,” he says.

In a diverse market like India, tweaking its strategy was imperative for Cinépolis. In keeping with the megaplex concept, the chain globally has an average of 10 screens compared with six here. Barely a year after it entered the country in 2007, Cinépolis signed a deal with Seasons mall in Pune for a 15-screen megaplex. This was after all the existing players had scoffed at the idea of such a large project. “People thought the developer was crazy. We actually came in quite late in the discussion process. Back then, a Mexican company sounded quite exotic to most people,” says Sotomayor. Having inked one deal, Cinépolis was convinced that the megaplex story was underway here. In almost no time, reality hit hard. “All the projects we signed that year didn’t take off and it was clear that we had to revise our expectations,” he recalls.

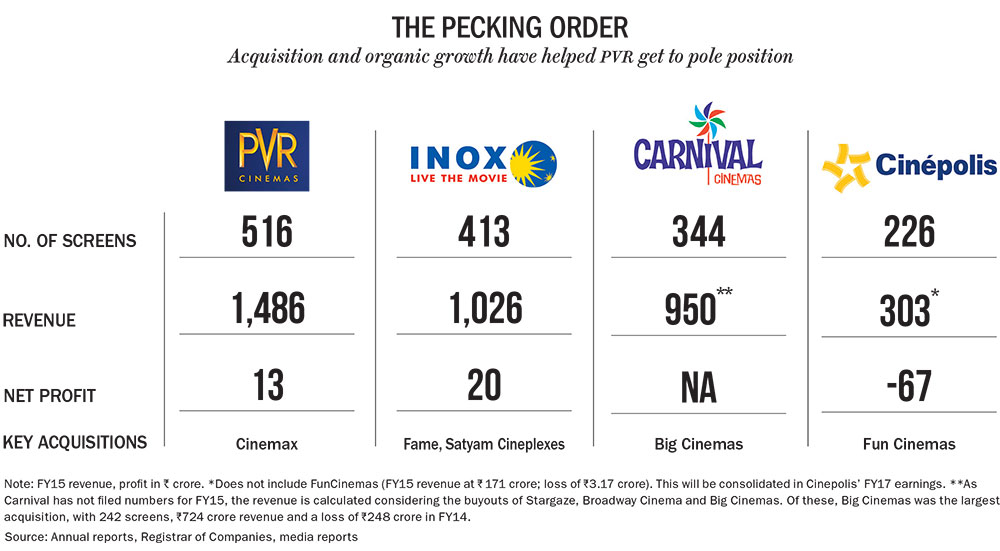

Besides, the time taken to get started once a deal was inked was a huge cause for concern. “In Mexico, the process takes six months. In contrast, we signed the deal with Seasons in 2008 and ended up opening the complex in 2013,” he explains. Changing its strategy, Cinépolis began opening four-screen multiplexes in centres such as Amritsar and Patna. “It was not our usual format, but it was better than not having any,” he adds. Post the Fun buyout, Cinépolis now has a presence in 31 cities, although the revenue kick will follow in this fiscal. Compared with competition, Cinépolis is still relatively small, with PVR and Inox boasting of 516 and 413 screens, respectively. For 2015, Cinépolis had a revenue of Rs.303 crore compared with PVR’s Rs.1,486 crore and Inox’s Rs.1,026 crore. On an operational level, the company broke even in 2013, shortly after setting up shop in 2009. While Cinépolis made a loss of Rs.67 crore in FY15, it hopes to hit profitability soon.

Apart from the multilingual challenge, India is a market that calls for a very different approach even in terms of topography. Cherag Ramakrishnan, MD, Ceear Realty, points out that while most countries in South America, where Cinépolis has met with success, have large cities with population upwards of 4 million, the cities are larger in size, with the population being more spread out. “In most cases, they often have just one very large mall and for a megaplex player like Cinépolis, getting a huge chunk of that space is not difficult at all. The story in India is very different,” he says. Here, there is a hyper-concentration of malls and multiplexes in most big cities. Worryingly, though, there have been no new projects in the metros over past few years; from 26 new projects in 2010, we were down to eight in 2014. This year, only 11 new launches are foreseen across the country. Besides, the real estate slowdown has put the brakes on the growth of multiplexes, with the intense competition leading to a wave of consolidation among the existing players.

A case in point: PVR bought Cinemax’s 138 screens in late 2012 for Rs.395 crore, while Inox acquired Fame for Rs.66 crore in 2010 and the Delhi-based Satyam Cineplexes for Rs.182 crore in 2014. Even a smaller player like Carnival has made its presence felt in this space by buying Big Cinemas’ close to 250 screens in late 2014 for Rs.700 crore. Interestingly, each of these deals came Cinépolis’ way but were never consummated. “Valuations are very high in India compared with the rest of the world. Since we have recently acquired properties in Chile and Spain, the truth is that India has to compete with our other markets,” explains Sotomayor. The deals listed above, coupled with continued organic growth, have helped PVR get to the top position, followed closely by Inox and Carnival. (see: The pecking order) “We are open to inorganic growth, but certainly not at any price. We have openly rejected offers because they did not make strategic sense,” he maintains.

So far, the company has spent Rs.1,000 crore on its India foray and is looking to spend another Rs.500 crore on its proposed expansion. While the investment for an average 200-seat Cinépolis megaplex starts at Rs.2.5 crore per screen, the outgo is bigger for fancier formats such as VIP, IMAX and its pet 4DX, which could cost as much as Rs.5 crore per screen. But this is the space where Cinépolis likes to operate and it is also its area of strength. “Tickets at our megaplexes are typically priced at a 25% premium compared with competition,” explains Sampat.

Thankfully, occupancy rates have slowly been moving up, both as a result of the better viewing experience on offer, strong content and larger number of discerning consumers. For Cinépolis, average occupancy has increased from 26% in 2011 to 30% in 2015, with PVR at 37% and Inox at 31%, too, having seen a similar increase during the same period.

What’s on

This is why Sotomayor is now hard at work trying to understand what kind of films work in India. Be it Prem Ratan Dhan Payo, Bajirao Mastani or Bajrangi Bhaijaan, he has not missed any of the big hits of last year, albeit with subtitles. Having the right content mix is critical in scripting the success of a multiplex, as ticket sales bring in 65-70% of revenue, with F&B and advertising bringing in the rest. Strong content not only brings more people to the theatre hall, it allows multiplex owners to raise ticket prices and charge more for F&B and ads. The usual revenue share agreement with distributors is around 50% of ticket sales in the first week, going down to 42.5% and 37.5% in the second and third week, respectively, with the distributor retaining a small buffer to increase or decrease prices depending on how the movie fares.

All of Cinépolis’ different formats have their own P&L, which means separate F&B offerings and individual booking counters. Coffee Tree, Cinépolis’ in-house F&B outlet, is open to all sections of the audience. F&B offers the highest margins — nearly 70% — for multiplex owners, and for Cinépolis, it contributes around 25% compared with PVR’s 24% and Inox’s 19%. Advertising, too, offers a superior gross margin of about 95% to multiplexes and currently brings 8% of revenue for Inox and 10% for PVR. For Cinépolis, ad revenue brings in 10% of overall revenue. This is why multiplex owners are consciously working on increasing average spend on F&B — which is currently around Rs.70 per person — by offering online pre-booking of food, seat-to-seat ordering and in-hall delivery of food, and hiking ad revenue by using technology to offer differentiated advertisements.

Fight for eyeballs

At this point, Cinépolis is the only foreign multiplex chain in India. But this could change soon, what with the likes of South Korea’s CJ CGV, the second largest player in Asia, actively scouting for opportunities. If Cinépolis is viewed as a premium offering here, CJ CGV is no different. Suniil Punjabi, CJ CGV’ strategic advisor and ex-Cinemax CEO, says the Korean major, which has both multiplex and megaplex operations, is looking at both organic growth and a strategic partnership with a national player. “We have been very successful with the latter in other parts of Asia,” he says. According to him, the consolidation phase in the industry is almost over and future growth will need to be organic. “Valuation expectations are very high and none of the players will be able to replicate the growth that they have shown over the past three to five years,” he says.

Clearly, the competition is intense and everyone wants a share of the average movie-goer’s wallet. According to a Merrill Lynch report, while PVR is planning to add 70-80 screens each year over the next three years, Inox has already signed agreements for 185 screens after FY16, having added 50-60 screens on an average over the past three years. In March this year, PVR opened its Rs.48-crore 15-screen superplex in Noida. Gautam Dutta, CEO, PVR Cinemas, thinks this project alone will generate an annual turnover of Rs.50 crore. This is PVR’s second innings in Noida, having exited the location in 2008. With the brand having a presence in Delhi, Gurgaon and Faridabad already, Noida was the next logical choice. “We had the option of starting four- or five-screen multiplexes. But being a new entrant meant we needed to do something bigger,” he explains. In addition to formats such as IMAX, 4DX and Gold Class, PVR has put in place Playhouse, which is a screen only meant for children. “We are looking to reach out to various audience segments in the same complex,” says Dutta.

Despite such stiff competition, Sotomayor remains optimistic. “We got it right in Mexico, where people watch films in just one language. There is no reason we won’t get it right in a multilingual country like India,” he quips. “We have been here for nine years; operating for six. We believe that our preferred model of megaplexes is right; it’s just that we couldn’t replicate it the way we wanted.” Nothing excites him more than the potential in India. Indeed, with over 900 releases and over 2 billion tickets sold each year, India is definitely a market that cannot be ignored. And while the limited supply of real estate does put PVR and Inox in a position of strength, making it difficult for Cinépolis to catch up, Sotomayor isn’t worried. After all, he isn’t obsessed about the number of screens he owns, preferring instead to be the viewer’s first choice. “We want this to be the No.1 market for Cinépolis,” he concludes.