In November 2015, Amazon surprised everyone by opening its first bookstore in Seattle. Imagine wading into the very arena that you had helped diminish, albeit 20 years later. Why was the e-commerce giant doing that? As analysts fished for answers, Amazon launched Project Udaan in India. The plan was to go offline by tying up with small traders and retail points such as mobile shops and medical outlets. “Over the past three years in India, we witnessed growing interest from people. But for many, who wanted to participate as active customers, lack of digital access, digital illiteracy, trust, language and payment processes acted as barriers. With the aim of addressing this,

we introduced Project Udaan,” says Kishore Thota, head, consumer marketing, Amazon India. The touch points would be the pickup location and the pay point, collecting a commission for every sale and also helping people without an internet connection to shop online. If omni-channel was gaining credence globally, the Jeff Bezos-led company had realised that it was even more important in India.

Into the fold

But Amazon is not alone. A clutch of companies, especially online start-ups are setting up physical stores to reach out to more users and bridge the inherent trust gap. Shabori Das, senior research analyst, Euromonitor International, points out another reason. “Consumers now have extremely low loyalty for brands and retail channels due to an increased supply of both. In a bid to improve loyalty and tap into the growing consumer base, retailers have to be present in more than one channel. 2015, thus, witnessed a large number of internet retailers going offline,” says Das.

Baby care platform, FirstCry, however, saw merit in going offline in 2011 itself, launching its first store in Gujarat. Supam Maheshwari, co-founder, FirstCry says, “Going offline helps in getting an additional set of customers, tapping that set of the population who’ll never go online.” Little wonder that FirstCry has since expanded its offline presence to 180 stores across 100 cities. To fund the expansion, it raised $36 million in its fourth round in 2015, taking the total fund-raise to $69 million from investors such as SAIF Partners and IDG Ventures. Mukul Arora, principal, SAIF Partners says that there are set rules for going omni-channel. “First, touch and feel of products must be important for customers. Second, the category should not be already flooded in the offline space. The baby care category met both these requirements and hence FirstCry decided to aggressively pursue the offline channel,” he says.

While the stores require an investment between Rs.35 lakh and Rs.1 crore, the capex and running cost is borne by the franchisee. Maheshwari says, “We charge a commission as soon as the product is shipped while the franchisee makes a markup on the sale. We don’t segregate any of it.” Supplies are handled via its three warehouses in Delhi, Bangalore and Pune. “For offline stores, the orders are sent in bulk. While for online, individual packets have to be delivered, which adds to the cost,” he adds. FirstCry stores generate an average footfall of 125,000 per month, with the average ticket size being Rs.1,200. “Online has a conversion rate of just 6-8%, but the conversion rate is 90% in offline stores,” adds Maheshwari. Conversion rates are higher in the offline space as consumers have already decided what product to buy and it’s just a matter of one final look.

The recent shop-in-shop approach by Amazon also cashes in on the same mentality. As part of the deal, Vodafone stores will feature select smartphones that have been launched exclusively on Amazon. The centres will not just give customers a first-hand experience of the handsets, but also help them make a purchase.

Look and feel

While the conversion rate is a big plus, Ankur Bisen, senior vice-president, retail and consumer products, Technopak says that the decision to tap a channel is not just driven by more revenue, but to enhance consumer experience.

For lingerie brand Zivame, it was about giving customers a way to try out its products. The business, launched in 2011, opened its first store about eight months back. “We offer a lot of choices and different sizes. Without trying these sizes, customers are usually hesitant to buy our products. We needed experience stores since touch and feel was really important,” says founder, Richa Kar.

For lingerie brand Zivame, it was about giving customers a way to try out its products. The business, launched in 2011, opened its first store about eight months back. “We offer a lot of choices and different sizes. Without trying these sizes, customers are usually hesitant to buy our products. We needed experience stores since touch and feel was really important,” says founder, Richa Kar.

As of now, Zivame has three company-owned stores and is looking to open four more. It sees about 700 footfalls per month, per store, with a conversion rate of nearly 70%. While the initial cost of setting up an offline store is between Rs.40 lakh-50 lakh, it takes about 18 to 24 months to break- even. Kar says, “Our costs are manageable, since we have an online business. We’re light on inventory as our stores just have trial products displayed.” The portal, which sees about 70,000 to 80,000 transactions per month, says that the offline approach adds a logistics cost of around 10%.

Lifestyle brand Chumbak is also busy investing in technology to ensure a seamless online-offline experience. It currently derives about 70% of its sales offline. “We retail through multiple channels and are using technology to enable omni-channel functionality. For example, a customer can make a purchase on the website and return it at the store, or place an order in a store and get it delivered in another city, etc,” says co-founder Shubhra Chadda. Evolving from an online souvenir store, Chumbak, today, has 15 company-owned stores in Mumbai, Delhi/NCR, Bangalore, Chennai, Hyderabad, Chandigarh, Kochi and Jaipur.

The stores, which are replenished twice a week, see an average footfall of 70-120 each day. Chumbak handles its own logistics to ensure efficiency and greater control. “In terms of costs, we’re very careful of the location and work a lot on the rent-to-revenue ratio. However, logistics costs continue to be high,” says Chadda. While she doesn’t reveal the ratio, she says, a ratio of around 20% is preferable.

Conversation starter

And, where others are using omni-channel as sales points to their advantage, furniture and home products e-tailer, Pepperfry considers them as experience stores. It has thus set up about seven studios, which are not sale points, but just a place to showcase its products. The stores are manned by designers. “They are great customer interaction points, where the goal is to help users by providing them advice related to interior design. They are solely meant to provide an experience and consumers still have to make the purchase online,” says Pepperfry co-founder, Ashish Shah.

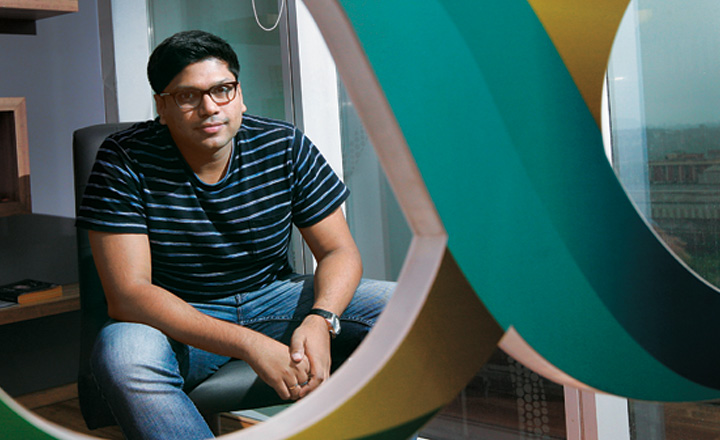

Peyush Bansal, co-founder, Lenskart though, thinks the benefit goes much beyond marketing or giving the brand a face. He says integrating the online and offline model helps them scale-up and build strong logistics. “Traditionally, the offline model has faced a lot of problems in terms of breaking even because of high real estate costs; use of the same stock, with no rotation and maintenance of huge inventory. An omni-channel presence helps us cater to many more customers. Since we dispatch goods from the centre, we don’t have to maintain a huge inventory at the retail store. And selling online helps in rotation,” he says.

Technopak’s Bisen agrees. “While conceptually an online model is better because of the cost structure, offline is much more efficient as its helps in scalability,” he says. Working on a franchisee model, Lenskart opened its first store in mid-2014. “We pay commission of around 25% to the franchisee as they incur the costs for running and maintaining the retail store,” says Bansal.

With a total investment of about Rs.700 crore, from the likes of Ratan Tata and Infosys co-founder Kris Gopalakrishnan, Lenskart has been beefing up its back-end. It has about 200 stores across 110 cities, with an average footfall of 50-100 per day. “A large part of the sales is directed by our website and includes people who have looked at our products online,” says Bansal.

While most of these franchisee outlets are regular stores in malls and high streets, some are shop-in-shop as well. The cost of setting up these stores is nearly Rs.20 lakh for 400 square feet. But Bansal says that they are able to break-even within three months. Logistics are handled by a third party and add around Rs.100/piece. “Once the customer decides the product at our retail stores, we deliver it to his address,” explains Bansal.

Copycat play

Online retailers are taking the offline route, but there is a two-way interplay happening here. Where start-ups are going offline, established brands such as Croma, Bata, Metro Shoes and many others are launching portals to tap into online retail. Farah Malik, CEO, Metro Shoes says, “The main motive behind our omni-channel investment is to meet customer expectations and respond to competitive pressure.” Similarly, The Body Shop, with more than 150 stores across 50 cities, is moving towards scaling its business online.

The trend suggests that India is following the US, UK and Australian markets, where large retailers have omni-presence. But being present across channels is not without challenges. Arora adds, “A lot of effort needs to be put into balancing inventory and receivables. A calibrated growth strategy and tight integration between online and offline are of utmost importance. But creating an offline segment independent of an online one will not work.”

The e-tailers, though, are forging ahead. FirstCry plans to open 120 new stores by March 2017, expecting to log revenue of Rs.1,000 crore overall, over the next two years. While Kar says that offline doesn’t offer the nimble-footedness that online does, the lingerie brand is looking to add 50 more stores by the end of 2017. For Chumbak, it’s 15 by mid-2017 and Pepperfry plans to set up 10 more experience studios by the end of 2016. It’s ironic, really! A few years back people were debating if offline will slowly die out. Going by the expansion plans, it seems e-commerce is happily moving in.