Masayoshi Son, often referred to as the big daddy of the investment world, addressing analysts in August in Tokyo said, “The world’s biggest hotel chain is Marriott. And how many monthly net room additions? 8,000. Hilton, the second biggest, added 7000; and Intercontinental, the third biggest hotel chain in the world, 2,000.”

This was just the context. He then mentions Oyo, the five-year-old Gurugram-based hotel chain founded by wunderkind Ritesh Agarwal. He is still 24 and has already spent half a decade setting up the business. “Oyo is less than a year old in China, and has added 25,000 rooms over the past two to three months,” said Son.

The 61-year-old sounds happy with the company in which he invested $512 million over the past five years. In September 2018, he led another financing round of $800 million in Oyo, which raised $1 billion from existing investors, including Lightspeed Venture Partners, Sequoia Capital and Greenoaks Capital. The recent round valued Oyo at $5 billion — an over 5x jump from its previous valuation of $900 million last year. The valuation is more than twice that of Indian Hotels, the country’s largest hotel chain. No wonder then that Son and other investors are optimistic about Oyo’s prospects.

New Voyagers

Oyo quietly entered China in November 2017 but formally announced its foray in June 2018. “In less than a year of entering the Chinese market, we’ve added over 87,000 rooms and 1,000 exclusive hotels to our chain. We are present in 26 Chinese cities, offering a combination of franchises and managed hotels,” says Agarwal. The room count puts the start-up among the top 10 hotel chains in China, where Home Inn is at the top with nearly 400,000 rooms. The cities it operates in include Hangzhou, Xi’an, Nanjing, Guangzhou, Chengdu, Shenzhen, Xiamen and Kunming, among others. Nearly 60% of the latest round of funding has gone into expanding in this market and taking on existing players. And there are heavyweights here, including established hotel chains such as Jinjiang Inn (a budget arm of the state-owned Jinjiang Hotels) and Home Inns (see: Enter the dragon).

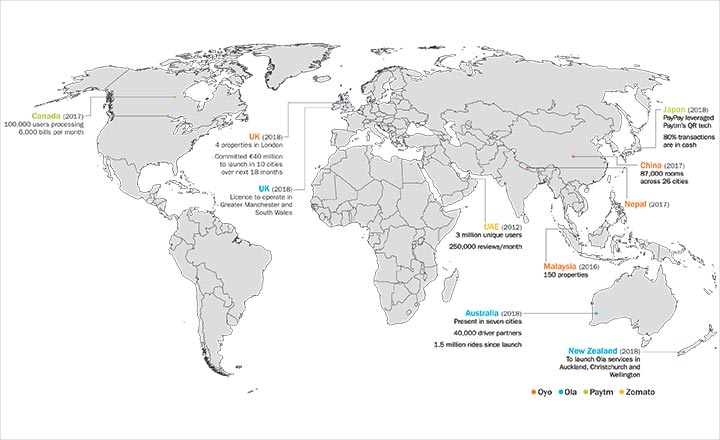

Outside of India, Oyo is now present in five countries — Nepal, Malaysia, China, the UK and the UAE. Globally, Oyo’s properties include 270,000 across 12,000 hotels. The most recent foray was into the UK, in September 2018, starting with four properties in London. Over the next two years, the company plans to invest £40 million in the UK, and enter 10 cities. Next, Oyo is heading to Japan, ahead of the Olympic Games in 2020 and Indonesia. The plan is to become the largest hotel chain in the world by 2023. Marriott is still the world’s largest hotel chain with an inventory of 1.28 million rooms.

Oyo, interestingly, is not the only unicorn that has expanded into other countries. Homegrown ride-hailing giant, Ola, first entered Australia in February 2018 and the UK in August 2018 followed by South Wales and Great Manchester. Then there’s Paytm, a near-household name in India. After Buffett’s high-profile investment, India’s highest-valued start-up is now worth $10 billion. In its international venture, the digital wallet first forayed into Canada in March 2017 and then in July 2018, indirectly entered the Japanese shores with a partnership with SoftBank. India offers a great opportunity for internet-based businesses. There is the potential billion consumers, besides demographic dividend, urbanisation, rising incomes and deeper internet penetration. Then, why are our highly valued, homegrown start-ups looking outside the country?

The investor community believes that none of these companies see the Indian market as exhausted or lacking in competition. “They are at a point where they can use the learning and practices developed in the country, outside it, without having to spend a lot of money,” says Karan Mohla, partner and executive director of Chiratae Ventures. Mohla cites one of their portfolio companies, Healthifyme — India’s largest health and fitness platform providing digital-only services — as an example.

“If they can utilise their AI platform, as well as nutritionists and coaches, at the back end, they can scale up internationally and benefit from the cost arbitrage,” says Mohla. Healthifyme is present in Indonesia, Malaysia and certain Gulf countries, with close to 30% of its 4 million users and revenue coming from overseas markets. Similarly, education-centric app Byju’s has also expanded into the Middle East because of its large population of Asians, especially from the Indian subcontinent. Its existing app got about 300,000 downloads in 2017 from Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries with 40% of them from the UAE alone. International expansion is part of the app’s growth strategy. It is preparing a product for markets such as the US, the UK and other Commonwealth countries too.

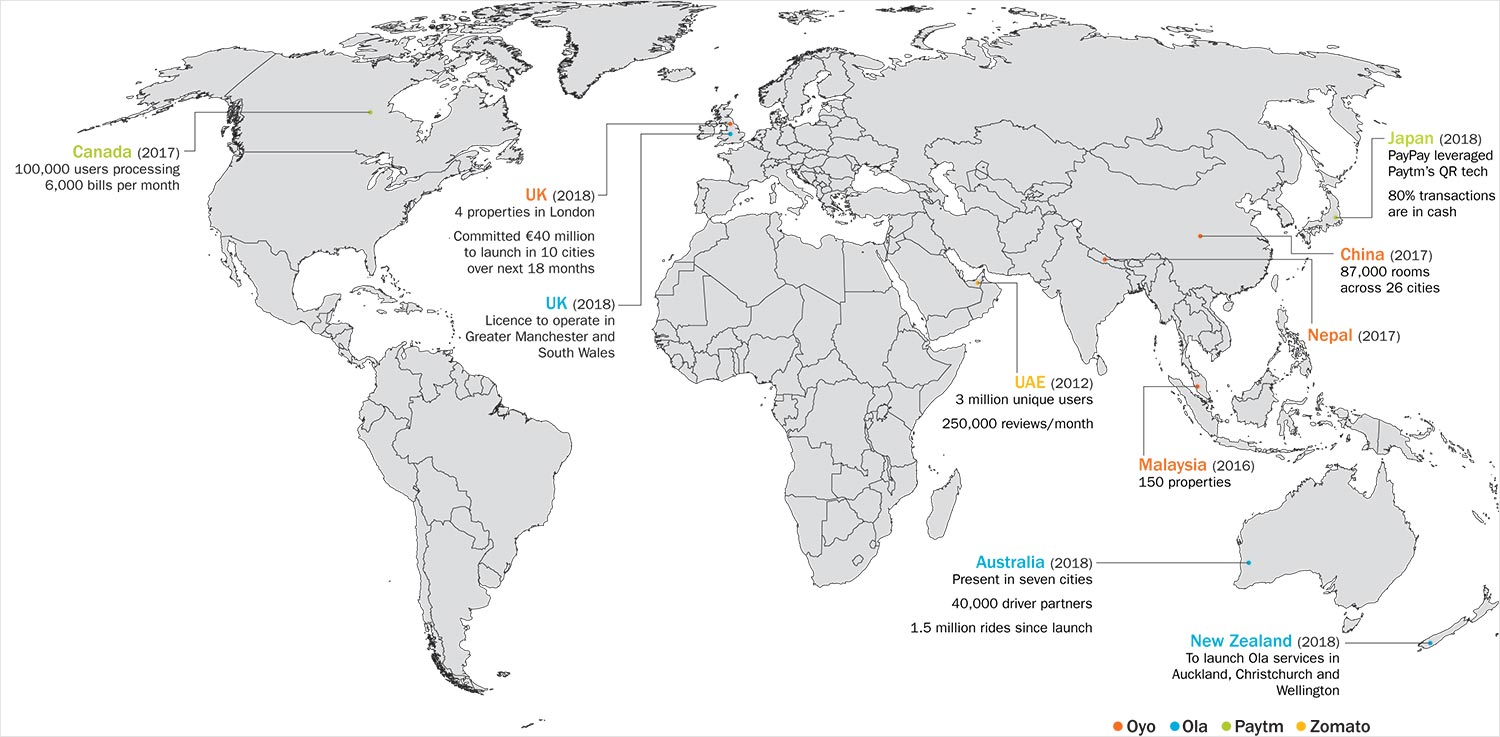

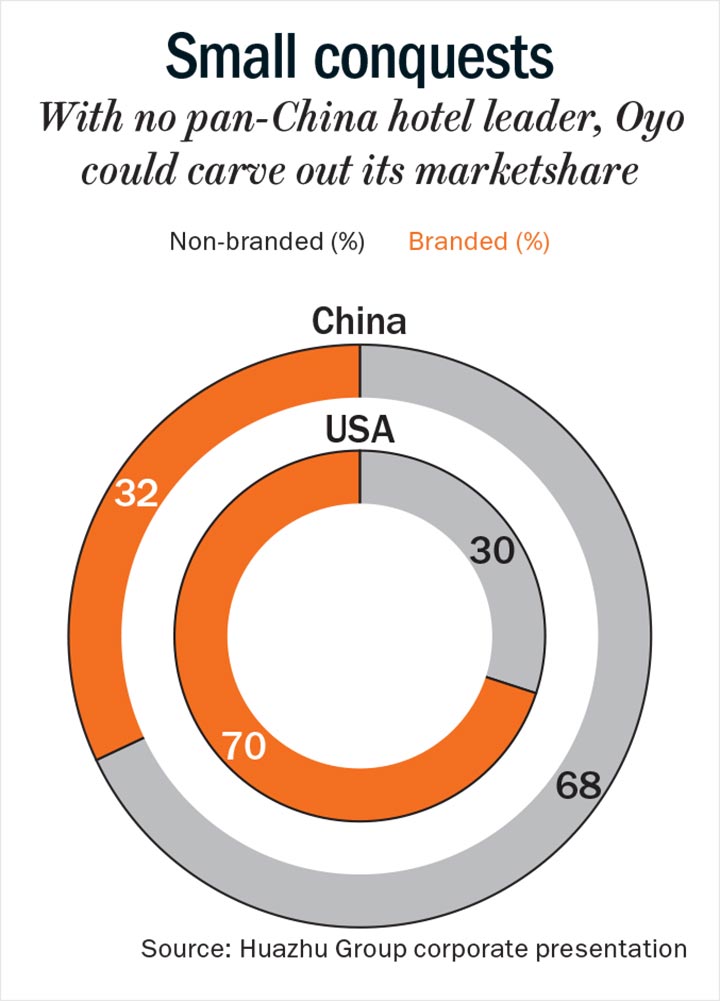

While Indian start-ups offer faster and cheaper services and products, they need to venture abroad and seek high-spending customers. It makes for better unit economics. “If you see the past five years in India, each delivery boy’s salary has doubled. Costs are going up. Customer volume is high for many a big start-up, but the paying capacity of each customer is not as high. The average ticket size has not gone up,” says Prerna Bhutani, partner, India Quotient, an early-stage investment fund. “In developed markets, people are willing to pay a good amount for services.” (see: Profitable units)

For the ride-sharing segment, the average revenue per user (ARPU) for a month is estimated to be $249 in the Australia market, $233 in the UK market, and $11 in India according to Statista. Similarly, if one looks at hotels booked online, the ARPU is $114.9 in China and $188.42 in the UK, far higher than that of India’s average of $89 per night.

Low ARPUs in India meant that Ola was spending more money than it earned in 2017. To be fair, no ride-sharing company in the world is making money. But, cash burn at Ola is much higher than Uber. In FY17, Ola’s losses were Rs.49 billion, more than 3x its revenue at Rs.13.1 billion. The same year, Uber’s losses were nearly half its revenue.

Mohla says that expansion allows Indian start-ups to split costs of operation — direct costs are incurred overseas while indirect costs are retained in India. “Design, software and engineering are done in India. Even if they (Ola, Oyo, Paytm) are paying the best salaries in India, they are much lower than abroad,” says Mohla.

But Ola’s foreign ambitions are driven by more than just better economics. Satish Meena, senior forecast analyst at Forrester Research says, “Their idea is to take some market share from Uber. SoftBank has invested in both the companies, and Ola wants to make a point to its investors that they can expand internationally. I am not sure how it will end — Uber spent a lot of money in expanding in the Chinese market, only to leave it after taking a stake in Didi.”

Ola is also resisting its lead investor SoftBank’s move to explore merger possibilities with Uber in India. The Tokyo-headquartered company has invested on both sides, in markets where it is a two-pronged battle such as Ola and Uber, and Flipkart and Snapdeal in India, and also Didi and Uber in China. To create a global alliance of ride-sharing companies, SoftBank has invested billions in companies in China, the US, Southeast Asia, India and Brazil and has also been instrumental in the merger of its portfolio companies. For example, in China and Southeast Asia, Uber sold its operations to Didi and Grab. In India, too, its investments in Uber and Ola have fuelled talks of consolidation. Ola’s Bhavish Aggarwal has been fighting this. In March 2017, he changed the ‘Articles of Association’ of the company, restricting SoftBank from buying any more shares of the company without the consent of its founders. He is also reported to have resisted SoftBank’s buyout of Tiger Global’s stake in Ola.

Oyo’s battles, however, are more of the operational kind. But, they have learnt their lessons from their five years in India, which can be used elsewhere. There is the expertise in managing a chain of hotels including putting in procedures such as property audits, done at regular intervals to ensure standards of service quality are maintained. Second, use of technology to improve productivity and occupancy levels where it resets room rates a million times in a day depending on the demand-supply. The hotel owner is given mobile apps to manage and monitor everything from inventory to housekeeping and billings.

Oyo’s Agarwal ventured into China also because he noticed similarities between the Indian and Chinese customers. “We started Oyo to solve the demand-supply imbalance in the India’s hospitality industry. In China, we saw a similar market opportunity — the country’s tourism industry is flourishing, and offers a tremendous opportunity with its market size of $44 billion and with a massive traveller base that includes 5 billion domestic travellers in 2017,” he says.

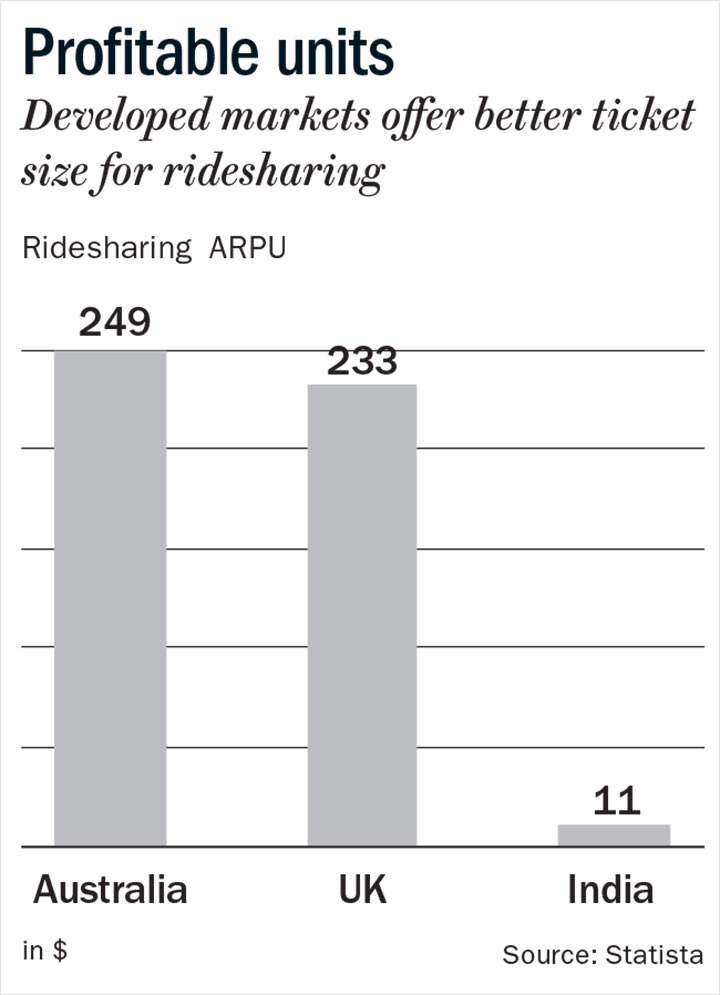

Despite being one of the fastest-growing hotel markets globally, China has a shortage of mid-segment hotels, which makes up only 6.8% of the total supply, according to a Bloomberg Intelligence report. Like in India, Oyo’s primary focus in China is on the middle-income class in the second, third, fourth, fifth and sixth-tier cities. It offers cost-effective living spaces available within ¥150-250. According to Oyo, the country has more rooms than India — 35 million compared to India’s 4.3 million. They also have a decent occupancy rate of 25%. But, they lack standardisation, which is the opportunity Oyo is going after.

The company says once the unbranded hotels get the Oyo makeover, occupancy levels will improve, like it did in India. While traditional hotel chains take 10 months to finalise management contracts, Oyo does it in 10 days, rating the property on several parameters. Then, within a month, the rooms are refurbished to meet Oyo’s standards. Costs are borne by the hotel owners and the aggregator gets a 25% commission on every booking done through its platform.

In the affordable category, there is no pan-China leader, says Meena. That is Oyo’s primary advantage in this market, according to him (see: Small conquests). “It is a fragmented market, plus the opportunity to scale is bigger than India. The number of travellers as well as expenditure on travel and tourism are high,” he says.

Oyo has also managed to get the support of local players, without which it is next to impossible to expand in the country. China has been difficult for everyone and that includes internet giants such as Google, Facebook, Amazon, and even Uber. “You have to deal with the authorities way more than any other market. Many companies have also failed because the local players are very strong,” says Yugal Joshi, vice-president at Everest Group, a research and consultancy agency.

“Oyo has a very interesting strategic investor, which is giving Ola strategic guidance on investing and expanding,” adds Joshi. Oyo has tied up with Huazhu (previously known as China Lodging Group), which invested $10 million in Oyo for a strategic stake. A five-year MoU has also been signed that includes technology and knowledge transfer.

Huazhu currently owns and operates over 3,000 hotels across over 350 cities in China. It is a multi-brand hotel chain, 12th largest in the world (fourth largest in terms of market capitalisation), offering luxury to economy class rooms.

The start-up’s ‘franchising’ and ‘manchising’ models are not new to China. However, Meena says, its edge may lie in two things. First, it is operationally slick, giving a quick turnaround. Second, it is a purely online platform, and the Chinese are more familiar with online booking than Indians. Online hotel booking in China reached ¥121.96 billion in Q1FY18, up 37.8% QoQ, according to a report by BDR, a Chinese data service. The fact that Oyo is still not present on China’s largest online travel agent, Ctrip, does put a dent on its ability to garner more bookings. The company is still relying majorly on offline and call centre bookings for customers. Says Agarwal, “Currently, we lease or franchise more than 1,000 hotels through multiple platforms including third-party distribution WeChat (mini app). We also host a large number of walk-in guests.” Apart from WeChat, Oyo is also now available on online travel agencies such as Qunar, eLong and Fliggy.

Tough climb

It goes without saying that new territories are not easy to conquer. In the Chinese market, Oyo had to face initial and peculiar hiccups. Oyo’s product head, who travelled to China to set up the technology, wrote in the company’s official blog, “Even mass communication is highly regulated by the Chinese government. SMS in India can be sent in any template, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) has no pre-set rules. In contrast, in China, even before a single message was sent out, we needed to get a template registered and approved from the authorities.”

Indian start-ups are used to working in a technology-enabled ecosystem where we take Google, Amazon, WhatsApp and Facebook for granted. But, with all of this regulated heavily by the government in China, businesses can get tricky. “Most global services, platforms and apps that we take for granted on our side of the (Great) Wall are either banned in China, or won’t work without VPN,” says the product manager. This required them to come up with alternate strategies of operations, while following the regulations. The company says that they operate like a Chinese company rather than a global company operating in China by giving local managers a lot of autonomy.

Some analysts are skeptical about their rapid expansion, which leaves a thin margin for error. A couple of bad experiences in a new market can cause a significant setback. “They may have rooms. If you have a local partner, you can visit properties and get them onboard. Then there are referrals from one hotelier to other as well. But customer onboarding is the challenging part. This is not Airbnb, so, existing brand awareness and trust is not there,” says Sreedhar Prasad, partner and head, consumer markets and Internet, KPMG. Most technology-led platform businesses, including Uber, Ola, Airbnb and Oyo, have seen their share of initial glitches and customer safety scandals, and will continue to do so in the future as well.

While Oyo will need to win the perception battle, Ola needs to find money to take on Uber. And it would be a massive amount, which not many non-SoftBank investors can cough up right now. The taxi aggregator had announced that it has raised $1.1 billion in October 2017 with Tencent leading that round, and that it was in advanced talks with investors to close an additional $1 billion as part of that round. It’s been a year since, but Ola is yet to close that additional round.

Being a late entrant in Australia also means having to give introductory discounts to customers. For instance, Ola currently pockets 7.5% of drivers’ fares as commission, with plans to increase that figure to 15%. Uber collects 20-25% as commission. At these rates, with Ola, Australian drivers can make $39/hour compared with $30/hour with Uber. It has already signed up 40,000 drivers, compared with Uber’s 85,000 drivers. Being the sole player for the past five years in Australia has helped Uber’s numbers — while Uber’s parent company made a loss of $6 billion, Uber Australia made a profit of $4.4 million. But, Ola drove into this market only this year, at a time when other plays such as Didi and Taxify have launched their operations too. The market is likely to see, as has happened in other markets, a contraction of margins.

Offering lower commission is not sustainable in the long-term and once Ola starts to hike the commission rates and reduce discounts, it will no longer enjoy the loyalty of the drivers and customers. Already in India, Ola and Uber are seeing their growth rates take a hit as they trim customer discounts and driver incentives. In 2018, growth declined to about 20% to 3.5 million rides across all segments compared with 57% growth (2.8 million rides) in 2017 and 90% (1.9 million rides) growth in 2016. While there has been growth in absolute numbers and the higher base effect comes into play, growth has been on a steady decline for both players.

Apart from the challenges that come with launching operations, a ride hailing company has to tackle regulators and policymakers. But in UK, it benefitted from being late to the party. Uber, its prime competitor, has already had run-ins with authorities in the UK already — its licence to operate in London was suspended, and only recently a court permitted it to operate provisionally for 15 months. “They have learnt from the experience of Uber in London. In the UK, Ola has smartly chosen markets such as South Wales and Greater Manchester, which are not highly unionised such as London with its black taxis,” says Joshi. Even as it continues to bleed, Ola is not hitting the brakes anytime soon and is looking to foray in 50 more global cities by 2019.

While big spending is essential to break into any new market, you can also overdo it. Like how Zomato did. The restaurant search-and-discovery platform had been the first to head overseas. Its expansion started back in mid-2012. Backed by large capital, four years ago, it started acquiring local players in the US, the UK, South America and New Zealand initially. Its first acquisition was New Zealand’s Menu Mania in July 2014. Then, it was online restaurant firms Lunchtime from the Czech Republic and Obedovat from Slovakia for a combined $3.25 million. In 2015, it bought Seattle-based food portal Urbanspoon, Turkey’s popular eatery search service Mekanist and the US-based NexTable, a restaurant reservations and table-management platform. By 2015, Zomato had expanded into 23 countries. But by early 2016, it was clear that it had spread itself too thin and expansion into high cost markets was burning a huge hole. Its losses shot up by 262% to Rs.4.92 billion in March 2016 from Rs.1.36 billion in the previous year.

It was around the same time that many food-tech companies started going belly-up and funding went dry. The markdown in Zomato’s valuation made fundraising tough. As cash crunch hit home hard, Zomato pulled back operations from 14 countries in 2016. Since their revenue pattern indicated that nearly two-third of its revenue comes from India and the UAE, the company decided to focus on these two markets.

“In the earlier days, we focused more on expanding our footprint, but that evolved towards strengthening our product offering in the countries we’re already functioning well in,” says Oytun Calapover, global head, listings business, Zomato. The decision to scale back and introduce new products in its core markets has worked better than the international expansion strategy.

“The US is a fairly competitive market with Yelp and OpenTable. Over the past three years, India’s competition also went up with the arrival of Swiggy and Foodpanda. A lot of it comes down to focusing on your core market,” says Mohla. In FY18, while revenue from operations improved 40% to Rs.4.66 billion, losses went down to Rs.1.06 billion from Rs.2.01 billion in FY17. The company has also fared better in the UAE, where it has over 3 million unique users and receives over 250,000 new reviews every month. “We launched the service in November 2016. Currently, we book over 350,000 tables every month. Our online ordering segment has grown by over 300% since 2016,” says Calapover.

Investor dreams

Indian unicorns have a natural need to expand beyond its home market, for the sake of sustenance. But, there are other factors at play too, such as investor ambition.

In the June 2018 analyst presentation, SoftBank’s Son spoke about his ‘cluster of number one’ strategy, where he talks about investing in unicorns that are, or could be, the number one players in the market. A look at SoftBank’s portfolio reveals quite a few of them there — Ola, Uber, Didi, Oyo, WeWork, Stripe, Arm, Paytm and more. Son believes that with this strategy, SoftBank would remain a high-growth company for as far ahead as the next three centuries.

At the same time, Son also stated that he wants his portfolio unicorns to synergise, which partly explains why his Indian unicorns are going all over the world. “We will see synergies between portfolio companies, which support and cooperate with each other, so that we can design new strategies with them,” said Son. No wonder, then, that Didi Chuxing was even rumoured to be investing in Oyo’s China operations. In July 2018, SoftBank, launched a mobile payment app PayPay in collaboration with Yahoo Japan. Son intends to utilise Paytm’s QR code expertise here, which it perfected in India. It offers ease of payment, which could change Japanese customer’s behaviour. The Japanese market is as cash-loving as India — credit cards, electronic money and other cashless systems account for only 29% of all consumer payments. In contrast, in China, the rate of cashless payments is 60% and in South Korea, 90%. Hiroyuki Miyamoto, partner at Nomura Research Institute, indicated in his report that there is a change in payment behaviour anyway: “The percentage of people who used electronic money at least once in the previous six months has been rising rapidly, up from 11% in 2010, to 18%in 2013 and 29% in 2016.” To grab a large chunk of the growing digital payment market in Japan, SoftBank-Paytm combine will be competing with Amazon, Rakuten (Japan’s version of Amazon), NTT DoCoMo (Japan’s largest telecom carrier) and Line (Japan’s version of WhatsApp).

Both Oyo and Ola are betting that having a significant international presence will help their fortunes when they go to the market for a listing. Son has also indicated that they might not wait for some of SoftBank Vision Fund’s companies to break-even before filing for IPOs. “Even before break-even point comes, there might be some companies in our portfolio that will be listed,” said Son at the Tokyo meet in August. Ola’s Aggarwal has already indicated that the start-up might be taking the IPO route in about three years’ time. Oyo, too, has set a five-year timeline for an IPO.

In this investor-founder Game of Thrones, the Indian consumer start-ups are crossing borders and going global. But the companies are still struggling to get on to the path to profitability and in cases such as Oyo, which clocked a revenue of Rs.1.02 billion in FY17 and an operating loss of Rs. 3.31 billion (down from Rs.4.63 billion in FY16), a $5-billion valuation does seem a little out of whack even factoring in future growth prospects. In a short span, when valuations increase multiple times over, there is enormous pressure on the company to cough up the numbers that match and execution starts to falter. Apart from Zomato, which also faltered in its international expansion, there are no Indian consumer tech companies that have truly been successful globally, as yet. Despite deep-pocketed investors with money on tap, expansion will not come easy for these Indian unicorns.