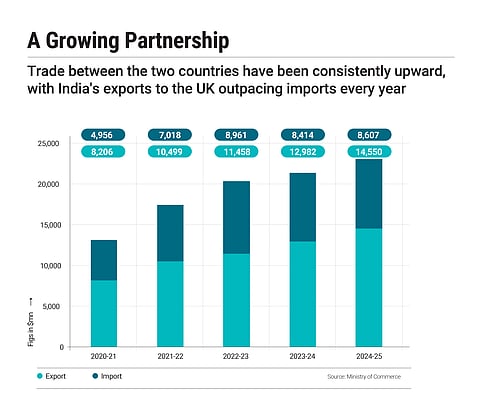

In a season of tariff tensions, trade wars and negotiations, India has pulled out a trump card of an entirely unexpected kind. On May 6, India and the UK finalised a free trade agreement (FTA), following 15 rounds of negotiations over three years.

How Small Farmers Wield Big Influence to Keep Dairy Off-Limits in Trade Deals

Despite bold trade moves, India’s dairy sector remains off-limits as a mix of protectionism and concerns over rural job loss continues to shape FTA negotiations

On the face of it, there is much to cheer about. Under the deal, which is the UK’s most substantial trade pact since Brexit, 99% of India’s exports will face no duties. In the shifting landscape of global trade, this arrives as welcome news for exporters across a range of industries—textiles, gems and jewellery, marine products and spices—who will now have unprecedented access to the UK market.

Another group of producers is also breathing easy for now—but for a distinctly different reason.

The dairy sector has been kept out of the purview of the deal on account of its sensitivities involving small farmers. Long viewed as politically influential and economically sensitive, dairy has historically pushed back against measures to open up the sector, citing livelihood risks to small farmers.

This resistance has often translated into special protections or leaving the sector out entirely from trade deals. In 2019, India dropped out of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) partly due to fears over the dairy sector’s exposure to dominant players. In India-EU FTA talks as well, dairy remains a sticking point.

Protectionist stance apart, this objection is also an indication of the formidable influence wielded by the dairy lobby. But as India dashes towards trade liberalisation, are entrenched domestic interests hindering its global ambitions?

Domestic Compulsions

India’s dairy sector, the world’s largest, employs over 80mn rural households, with 85% small and marginal farmers, according to National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (Nabard) data. Research suggests that in such a scenario, opening the sector could lead to 50mn job losses in rural India, which the government simply cannot afford.

"Agriculture, in general, is a globally protected sector. In India, it is also critical because it employs over 40% of its workforce. Usually, countries protect agriculture, either through tariffs or massive subsidies. The EU [European Union] gives subsidies, the US gives subsidies and Japan doles out massive subsidies on rice, for example. For India, dairy is part of the agriculture employment story,” says Sanjay Kathuria, visiting senior fellow at a think tank, Centre for Social and Economic Progress and co-founder of the South Asia trade-monitoring programme, Trade Sentinel.

For New Delhi, safeguarding this sector in trade negotiations is not merely protectionism, but a socio-economic imperative. Opening the market to foreign dairy—particularly to highly subsidised producers in the West implies undermining rural livelihoods and disrupting a finely balanced domestic ecosystem.

Then there is the socio-cultural aspect. “Countries have varying sanitary and phytosanitary measures for agri and dairy products. For instance, our rules do not allow dairy imports originating from cows fed on animal-based feed made from remains of slaughtered animals, which is the practice in some countries. For us, milk is a vegetarian product [and has] major socio-cultural sensitivities,” says Anup Wadhawan, former Union commerce secretary.

On the other hand, the domestic dairy industry is also highly competitive. International trade aside, state governments actively protect local dairy industries, which are closely tied to millions of jobs at the grassroots level. Often, this means protectionist policies to the extent that regional players struggle to expand within the country.

For example, Gujarat-based Amul sparked a political controversy when it announced plans to enter the market in Karnataka, where local brand Nandini holds a 70% share.

“Not only dairy, but also poultry and cereals need to be kept out of FTAs, as hundreds of millions of livelihoods depend on these products. Also, developed countries provide huge subsidies to their farmers. So, if we reduce tariffs on many of these products, Indian farmers will not be able to face subsidised imports from the UK, the EU or the US,” says Abhijit Das, trade expert and former head of Centre for WTO Studies, Indian Institute of Foreign Trade.

State of Exception

Even as the government fiercely shields dairy, a sense of betrayal is brewing among other sectors in agriculture and SMEs. The argument goes that if dairy can be safeguarded, why not other producers?

Farmer groups have vehemently opposed the FTA, fearing that it could expose domestic producers to a flood of imports from the UK. The All-India Kisan Sabha (AIKS) and Samyukt Kisan Morcha have criticised the agreement for easing tariff barriers on goods ranging from lamb and salmon to chocolates and other agri-based products, claiming that liberalisation would exacerbate agrarian distress and severely affect India’s manufacturing base, creating an uneven playing field ripe for exploitation by international capital.

“Our agriculture is mainly petty production. But in most advanced economies, agriculture is primarily reliant on large-scale production, business and corporate production. Indian farmers cannot make both ends—the cost of production and income—meet,” says P Krishnaprasad, AIKS finance secretary.

MSMEs involved in government procurement have echoed similar sentiments, wary of greater competition. Under the terms of the pact, India has granted access to its government procurement market, which will allow UK firms to bid for domestic tenders above a certain threshold and thus access a larger market than before.

This is in sharp contrast to other countries. A report by the think tank Global Trade Research Initiative states that less than 0.5% of procurement in the EU goes to non-EU suppliers. In the UK, too, only £20bn or less is awarded to foreign bidders. Indian firms, already lacking scale and familiarity with UK procurement rules, are unlikely to gain meaningful access to these markets.

In 2019, India dropped out of the RCEP partly due to fears over the dairy sector's exposure to dominant players. In India-EU FTA talks too, dairy is a sticking point

“Previously, we have seen that Indian MSMEs failed to get access to the Australian services market. There are several non-tariff barriers, licensing bottlenecks and Indian MSMEs struggle due to stringent safety standards. Despite zero duty, MSMEs face hurdles in terms of logistical costs, as we fail to associate tariff cuts with capacity building,” says Vinod Kumar, president, India SME Forum, a non-profit.

The case made here is that if the dairy sector is granted preferential treatment based on its social and economic importance, other small-scale players that are vulnerable to subsidised imports and the influx of raw material from abroad should also have safeguards in trade pacts.

For its part, the commerce ministry has assured that the government will take care of “sensitive sectors”, whether it is agri products or MSMEs. In a notification, the ministry said, “Market access to the UK would be limited to the non-sensitive central level entities only; access for sub-central (state/local government) level entities excluded.”

The ‘Sensitivity’ Stance

In determining which sectors are to be deemed ‘sensitive’ in trade negotiations, the government factors in political economy, rural employment and industrial self-reliance. Sectors involving large-scale livelihoods, particularly in rural areas, import-substitution potential and exposure to global price volatility tend to be ring-fenced in FTAs.

“Sensitivity depends on factors like how competitive that sector is [when it comes to] productivity and cost of production compared with trading partners. Our agriculture sector may lag in this aspect. [There are] also issues like numbers and economic condition of people dependent on the sector. Does the sector [provide] huge employment and low-income producers? [This] is true for our agri and dairy sectors,” says Wadhawan.

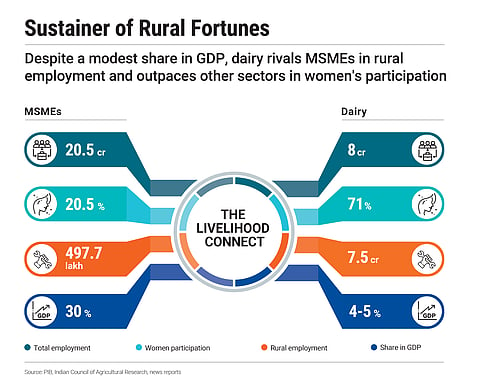

Data compiled by the Press Information Bureau shows that in 2024, 20.5 crore people were employed by Indian MSMEs registered on the Udyam Registration Portal, the official platform for MSMEs, and the Udyam Assist Platform, which supports informal enterprises. This included both formal and informal micro enterprises.

Out of the employment created by MSMEs registered on the Udyam Registration Portal, 18.7% is by enterprises owned by women.

When it comes to dairy, women’s participation is radically different. Women account for 70% of the total workforce. The workforce participation rate of women in dairy is thus nearly four times that of MSMEs. Informality in the sector also runs high and a majority of farmers are small, marginal or landless.

In light of this precarity, negotiators of trade pacts point to the need to balance economic liberalisation with domestic sensitivities. And as India plans to conclude several other trade deals by the end of 2025, the Ministry of Commerce continues to stand firm in its decision to guard the dairy sector.

This position is not softening in the near future, even as India eyes trade deals with the US, EU and New Zealand. Instead, the refusal to offer concessions on dairy reveals a calibrated strategy: willingness to open up some sectors and an equal determination to shield politically sensitive and employment-intensive sectors.

Within this framework, dairy not only complicates trade negotiations, it also shapes the final agreement. But in the attempt to balance rural livelihood and domestic interests, is India tipping the scales against its own trade competitiveness?