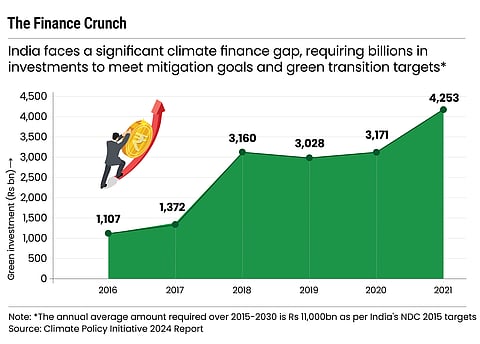

India’s ambitious green economy vision is a relentless capital guzzler. With investments worth nearly $2.5trn required by 2030 to meet its climate mitigation and renewable energy goals, the country, according to global research organisation Climate Policy Initiative, faces a yawning funding deficit—and must mobilise $67bn annually just for adaptation-related needs alone.

Fragile Green Bond Market Exposes the Limits of India’s Net-Zero Push

India’s green bonds are struggling to find takers. And that failure isn’t just a fiscal footnote—it strikes at the heart of the country’s climate-change goals

But the world’s largest democracy is increasingly finding itself alone in this journey. With the US—under the unpredictable leadership of President Donald Trump—having earlier reneged on key climate commitments, India cannot count on consistent global solidarity. The road ahead, as recent events show, is fraught with financial potholes.

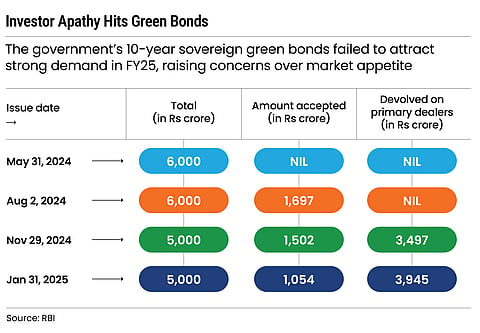

The strain is visible in plain sight. The government’s initial plan to raise Rs 32,061 crore through sovereign green bonds—debt securities issued explicitly for environmental projects—in 2024–25 has already hit resistance.

In January, the RBI partially devolved Rs 3,945 crore worth of 10-year sovereign green bonds on primary dealers after muted investor response. Devolvement of bonds on primary dealers—bond houses that buy government securities and sell them to their clients—typically happens when demand is lacklustre.

Of the Rs 5,000 crore on offer, bids worth only Rs 1,054 crore were accepted—a dismal showing. Just two months earlier, in November, another Rs 5,000 crore tranche suffered a similar fate, with more than two-thirds of the issuance landing with primary dealers.

Among the first casualties of this resistance are grid-scale solar projects, whose budgetary allocation has plummeted from Rs 10,000 crore to a mere Rs 1,500 crore. In a country chasing sunlight, the numbers are beginning to cast long shadows.

India has made it clear that it wants to be a leader in the global energy transition. But numbers show that its financial architecture isn't yet built to carry that weight

Despite the rhetoric and resolve, India’s green bonds are struggling to find takers. And that failure isn’t just a fiscal footnote—it strikes at the heart of the country’s climate-change goals.

“The Indian green bond ecosystem is more dependent on international markets rather than domestic players,” says Sarnambar Roy, chief analytical officer at Infomerics Valuation and Rating, a domestic credit-rating agency. “Liquidity issues and weak investor demand coupled with limited green ecosystem in the country have led to cancellation or devolvement of these sovereign green bonds on primary dealers.”

Costly Affair

Unlike traditional infrastructure projects, green initiatives often demand cutting-edge technology, long gestation periods and higher upfront capital. Building a solar park may win applause at climate summits, but on the ground, they strain already stretched public finances.

And India’s ambitious green finance vision is floundering on the rock of hard reality. The country is able to mobilise just 30% of the $170bn it needs every year to meet its climate goals that it has boldly set for 2030. The question arises: why is it not able to bring funders on board? An obvious reason is optics.

“Indian investors are hesitant to pay premiums for environmental, social and governance [ESG] initiatives and to engage in social good,” says Suresh Darak, founder of Bondbazaar, an investment-services provider. “To jumpstart this space, we should consider giving certain incentives such as tax advantages for investors.”

Matters had initially looked promising. When the RBI debuted its sovereign green bonds in early 2023, the response was electric. The Rs 16,000 crore maiden issue was oversubscribed nearly four times. It seemed, for a brief moment, that India had found a viable channel to fund its climate ambitions. But the optimism faded quickly.

On May 31, 2024, the RBI was forced to cancel its first green bond auction of the fiscal after investors demanded higher yields than the government was prepared to offer—a signal that investor sentiment had shifted. The second attempt fared little better. Although it managed to raise Rs 1,697 crore, that figure fell well short of the Rs 6,000 crore target.

“Ours is a developing economy, and possibly we may take some time for investors and corporates to actively spend time and money in such initiatives. Moreover, given the current volatile global macro-economic situation and potential slowdown in growth, investors might be more focused on stability and known instruments,” adds Darak.

Handful of Traders

Unlike conventional government bonds, green bonds are supposed to offer the government a slight financial advantage—a “greenium”, or green premium. This means investors typically accept slightly lower returns in exchange for the environmental benefits their money is funding. But in India’s case, that hasn’t happened.

The problem is economic. Green bonds, by design, are meant to make risky, capital-intensive sustainability projects financially viable—ventures that might otherwise be too expensive to fund. But a thorny question keeps surfacing: why would anyone accept lower returns for a bond that isn’t all that different from a regular government security and also fewer in number?

When the government floated its first sovereign green bonds, public-sector banks and insurance companies, typically risk-averse, absorbed the bulk. Foreign investors registered with the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi) also showed a willingness to play along. So, when uptake faltered, the RBI tried expanding the pool, opening the gates to eligible foreign investors based in the International Financial Services Centre (IFSC). The hope was that global capital, once given access, would respond with a moral nod. It didn’t.

Even those who embraced India’s green bonds early on appear to be rethinking their enthusiasm. Unlike conventional government securities, green bonds do not trade as frequently. There simply aren’t enough of them in circulation. That thin market makes it difficult for investors to sell the bonds quickly if they need cash. In a market obsessed with liquidity, this is no small flaw.

“It’s like having another 10-year security. And since it can’t be traded in the secondary market, no one will take large positions on this,” says Vikas Goel, industry veteran and former chief executive of PNB Gilts, a government securities dealer.

In this climate of caution, the only path forward may be to first increase their numbers which can happen only when demand for such instruments increase. And demand would increase only when green bonds seem worth it.

Low on Confidence

A growing number of market participants believe the government must offer tangible incentives to kindle investor interest and develop the market. In an emerging economy like India, where capital is pragmatic and follows returns, not rhetoric, ideals alone won’t move money.

Still, the Ministry of Finance hasn’t given up on its approach. Of the Rs 14.82 lakh crore it plans to borrow from the market in the 2026 financial year, more than half—Rs 8 lakh crore—is scheduled for the first half alone. This includes Rs 10,000 crore worth of sovereign green bonds.

But behind the scenes, optimism is fading. Officials familiar with the matter say the government is approaching this round more cautiously. Rather than doubling down on green bonds, it is testing the waters, aware that investor sentiment is unlikely to shift dramatically this year.

“For all the effort and cost that goes into identifying projects and getting bond ratings, the benefit has translated to a mere one or two basis points,” Chief Economic Adviser V Anantha Nageswaran remarked at the 2024 Raisina Dialogue. “There’s a lot of talk about funding the energy transition and addressing climate change. But much of that talk, in truth, remains just that.”

The Green Deadlock

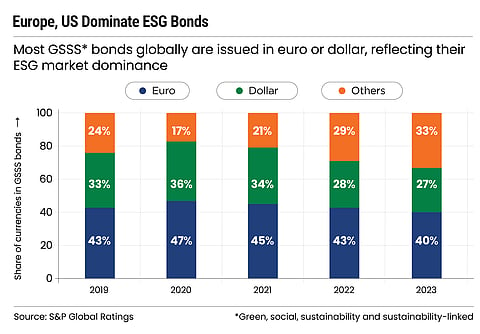

India may not be able to come up with a blueprint to develop its green finance market but the same cannot be said of the rest of the world. Globally, green bonds are not just surviving—they’re booming.

In the US, for instance, tax incentives for green bonds have been part of the policy fabric since 2009, supporting everything from renewable energy to green building projects. China, not known for hesitation in matters of scale, proposed tax exemptions for labelled green bonds—formally certified as such by a third party—back in 2015. This was to allow institutional investors to treat them as equivalent to treasury assets, which, by government estimates, would slash funding costs by up to 100 basis points.

Investors in India, for their part, have made their stance clear: no incentives, no enthusiasm. And yet, the government—having spent much of the past decade offering concessions to woo private capital with underwhelming results—now has its own reasons to dig in its heels.

“The idea of green bonds was not to find a new way to give tax concessions,” former Finance Secretary TV Somanathan told Outlook Business in an earlier interview. “Green bonds are supposed to be about people who want to keep their portfolios aligned to their moral and public policy objectives.”

Green bond, as a concept, is fairly old. It emerged in 2007 when the European Investment Bank issued the inaugural bond. India, however, waited—16 years, to be precise—before formally joining the sovereign green bond club.

That delay was telling. It wasn’t just bureaucratic inertia; it reflected both a lack of urgency and a keen awareness that investor appetite was, at best, uncertain. But as India's climate commitments grew louder, it found itself cornered into action. Eventually, it took a calculated gamble: that somewhere out there was a community of investors willing to support its green aspirations.

Whether it was blind faith or a misreading of market sentiment, that bet has landed the government in a quiet standoff with investors it once counted on. The bonds are here. The money, however, is not.

This isn’t just a funding gap. It’s a credibility gap. India has made clear it wants to be a leader in the global energy transition. But as the numbers show, its financial architecture isn’t yet built to carry that weight.

All of this makes India’s green transition not just ambitious, but acutely challenging. Without a focused strategy and with limited investor appetite, the country is left trying to a build a 21st-century energy future on a 20th-century financial foundation.

Unless India rewires its financial strategy—or the world rethinks how it values sustainability—the promise of a greener tomorrow may remain suspended in the haze of good intentions.