Sujith Kumar has made up his mind. He will not return to the city.

State Freebies and Low Factory Wages are Choking India’s Growth Engine

Stagnant wages and a slew of government social-welfare schemes are key reasons why workers are preferring to shun factory jobs

At 29, he has seen enough of Delhi—the cramped quarters near open drains, the relentless hammering at construction sites, the fleeting promise of better wages always undercut by the weight of survival. For years, the capital had seemed like his best chance.

But when the pandemic lockdowns swept through the country, shutting down work overnight, he was forced to return to Lakhisarai, his home district in Bihar. Back then, the journey felt like an admission of failure, a retreat from the dream of a better life.

Now, he sees it differently.

“I have a roof over my head here. I have my wife by my side. Why should I go back to a place where we lived like animals, near gutters?” he asks.

The Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana, the government’s food-security programme, has ensured that his family does not go hungry. In the meantime, Kumar has built something of his own—a modest poultry farm, a business that allows him to stay home while earning a livelihood. The numbers may not match a city pay cheque, but the cost of living is lower, the air much cleaner and, most importantly, he is not alone.

Kumar’s decision to stay home is not just a personal choice—it is part of a social upheaval that is unsettling India Inc boardrooms.

Infrastructure major Larsen & Toubro’s (L&T’s) chairman, SN Subrahmanyan, voiced his frustration at an industry event in Chennai earlier this year over what he sees as a troubling trend. “Labour is not willing to move for opportunities,” he said. “Maybe their local economy is doing well, maybe it is due to the various government schemes.”

For Subrahmanyan, the maths is daunting. L&T needs a steady workforce of 4,00,000. But with workers cycling in and out at a staggering rate—attrition hitting three to four times a year—the company ends up employing roughly 16 lakh people annually just to keep projects running.

L&T’s struggle is hardly unique. The infrastructure sector, once a magnet for rural migrants, is now facing an acute labour crisis. According to data from TeamLease Services, a staffing-services provider, India is short by more than 15 crore workers—a sharp rise from 13.8 crore recorded in 2020.

Trauma Lives On

When India locked down in 2020, the hardest hit were not the corporate offices that shifted to Zoom meetings or the factories that temporarily shut their gates. It was the daily wage labourers who found themselves stranded, suddenly without money, work, or even a way back home.

A survey conducted by Azim Premji University between April and May of that year painted a stark picture: 77% of households reported eating less than before the lockdown, while nearly half—47%—did not have enough money to buy even a week’s worth of essentials. The economic blow was severe, but for informal and migrant workers, it was something more—a collapse of the fragile arrangement that had kept them tethered to city life.

For many, the journey back to their villages was not just an escape from desperation, but the beginning of a reckoning. Would they ever return? Did they need to? The answer, increasingly, seems to be no.

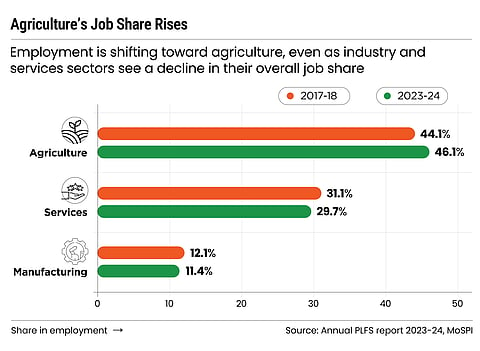

Despite the corporates’ efforts to lure workers back, the post-pandemic labour market suggests a different reality. According to data from the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) 2023–24, agriculture—once seen as the sector people left behind—has absorbed even more workers. Its share of total employment rose from 44.1% in 2017–18 to 46.1% in 2023–24, a reversal of decades of urban drift.

The shift is particularly pronounced among women. In 2017–18, 57% of female workers were engaged in agriculture; by 2023–24, that figure had surged to 64.4%. In contrast, male workers are not so much fixated on agriculture but rather taking jobs in construction, trade, hotel, restaurant, transportation, storage and communications.

At the same time, sectors once emblematic of India’s urban economic rise—manufacturing and services—are quietly ceding ground. Manufacturing’s share of employment has dipped from 12.1% to 11.4%, while services have slipped from 31.1% to 29.7%. On top of all this, self-employment has expanded—from 52.2% to 58.4%.

“Self-employment is a very grey area,” says Pronab Sen, economist and former chief statistician of India. “On one hand, there are aspirational workers, and on the other, distressed labourers. But if there is a sudden spike in agriculture and self-employed activities, then there is clearly stress in this segment.”

The distinction is crucial, Sen adds. Some may be turning to poultry farms or small businesses by choice. But many others—those who once worked on factory floors—are not so much choosing to stay back as they are left with little alternative.

Empty Trains

A study by the late economist Bibek Debroy and Devi Prasad Misra, “400 Million Dreams”, points to an unmistakable trend: fewer people are moving. Passenger movement data, often a proxy for migration patterns, shows that non-suburban second-class travel declined by 11.8% between 2012 and 2023. Meanwhile, India’s population grew by nearly 15% in the same period.

The numbers suggest a shift in the country’s economic geography. In 2011, Census data recorded 455mn migrants across all categories, pegging the migration rate at 37.6%. But by analysing railway passenger trends, Debroy and Misra estimated that the migration rate has since dropped to 28.9% as of 2023.

According to “400 Million Dreams”, the decline in migration is not solely about disillusionment with city life. It is also about what has changed in the places people once felt compelled to leave. Localised economic growth and improved infrastructure—better roads, schools, health care and public transport—has made small towns and rural areas more livable.

Various social-security schemes such as free ration and direct cash transfers provide a cushion, reducing the desperation that once drove millions to urban labour hubs.

Bharat Shining

There is also a quieter shift underway. Rural India, long seen as the country’s economic underbelly, is beginning to outshine the cities. For the second year in a row, the government’s Household Consumption Expenditure Survey has pointed to a surprising trend: the gap between rural and urban spending is narrowing. While still significant at 70%, it has shrunk by 14% over the past 12 years, a sign that the village economy is no longer as stagnant as it once seemed.

Passenger movement data, often a proxy for migration patterns, shows that non-suburban second-class travel declined by 11.8% between 2012 and 2023

“Some of the transfers made to people have indeed helped boost consumption,” says Manoj Govil, former expenditure secretary, Union Ministry of Finance. “Therefore, the steps taken by both central and state governments are useful.”

The latest survey, covering August 2023 to July 2024, reveals that rural per capita spending grew by 9.2%, reaching Rs 4,122 per month. In contrast, urban spending rose at a slightly slower pace—8.3%—to Rs 6,996.

This surge in rural spending has not gone unnoticed. But even as policymakers and economists debate its implications, India’s highest court has raised a sharp, uncomfortable question: “Are we not creating a class of parasites?”

Justice BR Gavai, while recently hearing a case on shelter homes for the homeless, remarked that rather than integrating people into the workforce, these schemes were fostering dependence. “Unfortunately, because of these freebies...people are not willing to work,” he said. “They are getting free ration, they are getting an amount without any work—why should they [work]?”

The tension between welfare and work, between state support and self-sufficiency, is not lost on policymakers.

For Sanjeev Sanyal, a member of the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister (EAC-PM), told Outlook Business in an earlier interview, the real question isn’t what governments provide—but what citizens demand.

India’s rural workforce seems to have made its choice. It is not asking for factories. It is asking to stay home. And the state, in turn, is listening.

Bring them Back

India’s ambition to become a developed nation by 2047 hinges on large-scale industrialisation, infrastructure expansion and a thriving manufacturing sector. These goals demand a steady supply of workers willing to migrate, take up factory and construction jobs, and power the country’s urban economy. If rural India turns inward, the labour shortages already gripping industries today will only worsen.

Amit Basole, an economist at Azim Premji University, sees this trend to be reversed only by high-paying jobs in cities. “In the case of people who have less education, it’s really about creating the kind of high-productivity jobs in manufacturing that other countries have managed to do—like China, or before that, South Korea, and now Vietnam," he says.

While lamenting the reluctance of workers to relocate, L&T's Subrahmanyan also acknowledged that Indian workers heading to West Asia earn nearly 3–3.5 times what they would make at home.

But if the solution to India’s labour crisis were simply a matter of wages, why did the country’s industrialists allow wages to stagnate to the point where workers now refuse to return? The answer, Basole explains, lies in the longstanding assumption of an endless, replaceable workforce.

"Once private-sector employers realise they need to pay more to attract and retain a good person—that’s when wages will rise."

Until wages in India reflect the true cost of labour, Viksit Bharat may remain an aspiration that lacks the hands to build it.