Nirmala Sitharaman is the finance minister of the fastest-growing major economy in the world. She joined politics in 2007, became a Union minister in 2017 and only last year, Forbes magazine ranked her among the most powerful women in the world. Yet, when Sitharaman was asked why she was not contesting the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, she said, “I do not have that kind of money.”

How much money does it take to contest an election in India? An Outlook Business analysis of the amount of money spent by candidates who won the 2019 Lok Sabha elections found that an average member of Parliament (MP) spent around Rs 50 lakh on their campaigns. This was nearly 25% more than the average amount spent in 2014 and 67% more than in 2009.

The analysis is based on declarations made by candidates to the Election Commission (EC) and compiled by the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR).

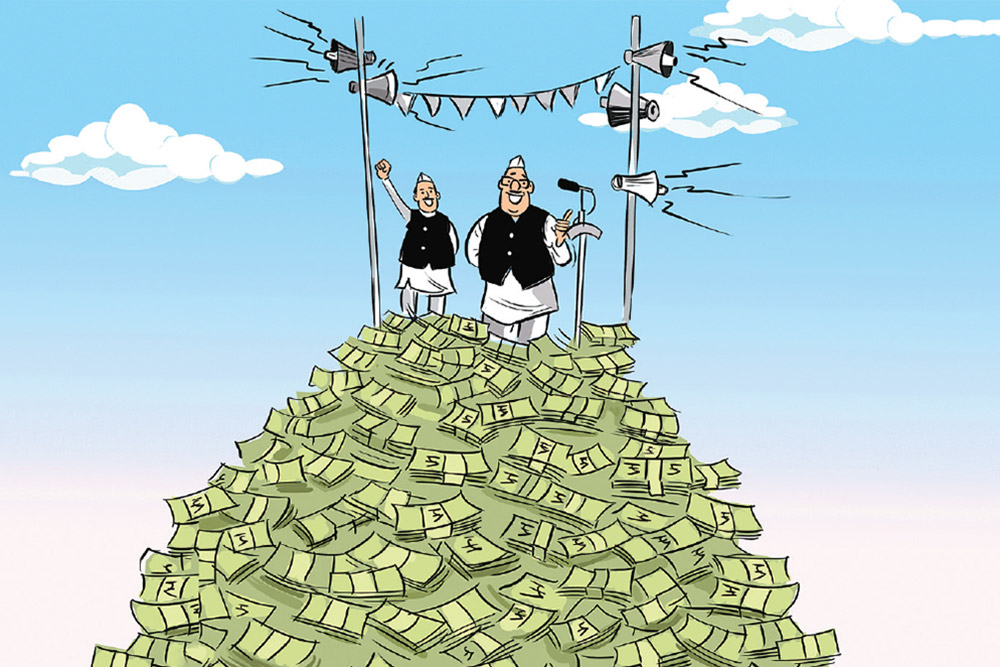

An obvious consequence of the rising cost of elections has been a rise in more financially privileged people coming into Parliament. The 17th Lok Sabha, elected in 2019, had 474 members with assets worth Rs 1 crore or above, nearly 88% of the House.

Spiralling Costs

The 2019 Lok Sabha elections were called the “most expensive elections ever, anywhere”. Chances are that the ongoing elections will break that record. Poll expenditure in India went up over five times in the 20 years between 1999 and 2019. Around Rs 55,000–60,000 crore was spent on the 2019 Lok Sabha elections. In 1999, that amount was Rs 10,000 crore. Five years later, that cost went up by 40%. Between 2009 and 2019, the total expenditure on elections went up by around 175%, according to estimates by the Centre for Media Studies, a Delhi-based media research organisation.

In 2009, an average candidate who went on to win elections had spent around Rs 30 lakh. In the next general election, it went up to Rs 40 lakh. In 2019, the average winner’s spending on elections went up further to Rs 50 lakh. These are just winning candidates’ expenditure on campaigns and do not include the expenses made from the centralised kitties of political parties.

The EC puts a cap on the amount of money a candidate can spend on their campaigns. As of 2014, that amount is fixed at Rs 95 lakh per Lok Sabha constituency. However, there is no such cap on spending by parties. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) spent around Rs 755 crore on party propaganda in the 2019 Lok Sabha polls, not accounting for the amount spent on candidates. Congress spent around Rs 488 crore, according to declarations made by the parties.

Experts say expenditure that candidates and political parties declare is only “the tip of the iceberg”, and actual expenditure is significantly more than what is declared. “A candidate can be given Rs 95 lakh in cheque and the party can spend several crores and that is legal as there are no restrictions on that,” says former chief election commissioner (CEC) S.Y. Quraishi.

Roadshows by leaders such as Rahul Gandhi and Narendra Modi are a major expenditure head for political parties during poll campaigns. Photos: Getty Images

More Not Always Merrier

One of the reasons why election expenditures have ballooned over the years is the expanding size of the electorate, says Chakshu Roy, head of legislative and civic engagement at PRS Legislative Research, a Delhi-based non-profit that seeks to make the legislative process more informed. Roy says that when the first general elections took place in 1951, an MP represented around 8 lakh people. “This number has currently swelled to 25 lakh...The burden of representation per MP has gone up because the number of seats in the Lok Sabha has remained unchanged since the late 1970s,” he says.

The number of people a candidate must reach out to has increased, thereby increasing the money required to be spent on campaigns, says Sandeep Shastri, a political scientist and steering committee member of the Lokniti programme of the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), Delhi. Another reason why elections are getting expensive is the nature of competition, he says. “The stiffer the competition becomes, the more is the expenditure a candidate needs to make in order to ensure visibility across a constituency,” Shastri says.

Candidates must spend money on handbills, posters, loudspeakers plus advertising. A significant amount of money is spent on campaign workers. Political parties bear part of the expense but in many cases a large chunk of the expenditure is borne by the candidates. The CMS study says that national parties pass on money to state units specifically for election expenditure. Some advertising on social media and print is paid for by the parties.

Parties, especially the bigger ones, often opt for political consultancy groups to prepare them for elections and make heavy investments in digital marketing. While an estimate of the amount of money spent on campaigns run by these consultancies is not publicly available, digital advertisement has significantly gone up.

Ahead of the 2019 elections, the BJP spent around Rs 12 crore on Google ads, the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) around Rs 4 crore and the Congress around Rs 3 crore, according to data from Google Ads Transparency Centre. The size and costs of social media campaigns have since swelled. Between March 31, 2023, and April 1 this year, the BJP spent more than Rs 42 crore on Google ads. The Congress, in the corresponding period, spent around Rs 19 crore.

Social media has become one of the more popular ways in which parties and candidates reach out to voters at relatively less expense. The 2019 Lok Sabha elections were the first to see widespread spending on social media campaigns. But even that came to just around 1% of the total amount spent on elections, according to reports based on data published by social media companies.

But over the past five years, a record number of Indians have come on social media. More than 36 crore Indians are on Facebook as of March 2024, according to a Statista estimate. Consequently, parties have started investing more in social media. In just the past four months, the BJP spent over Rs 6 crore on Facebook, according to Facebook Ad Transparency Centre. Congress, in the corresponding period, spent around Rs 1.45 crore.

Apart from centralised social media campaign teams, local units of political parties often have their own teams and individual leaders run their own teams as well. Many political parties also run proxy pages wherein an individual without direct association with the party may run a social media campaign on behalf of the party, a source said.

In 2019, a CSDS-Lokniti report titled Social Media and Political Behaviour said the impact of social media was limited, with just about one-third of the Indian electorate having a presence on social media and about one-tenth of them using social media extensively. That may well change this time. Social media use back in 2019 also differed widely in terms of regions, wherein it was found that eastern states had a much lower presence on social media than their northern or southern counterparts.

House for the Moneyed

Rising costs of election have led to a sharp change in the financial profile of Indian lawmakers. Roughly 20 years ago, days ahead of the 2004 Lok Sabha elections, Atal Bihari Vajpayee had almost prophetically spoken of the dangers of money becoming critical to the electoral process. “Janatantra dhanatantra me badal raha hai [The rule of the people is turning into the rule of money],” he had said.

Vajpayee, a politician who had contested elections since 1957, had said that the state of affairs was such that only the rich could fight elections and that it was fortunate that people who were making large monetary contributions to politics were not seeking favours in policy. “I think this could become a curse for the country,” he had added.

In the elections that followed, 153 candidates with assets worth Rs 1 crore each entered the Lok Sabha. The next general election, 2009, the number of MPs with assets worth Rs 1 crore and above rose to 302. At 58% of the Lok Sabha, crorepatis now formed a majority in the lower House. In 2014, that number rose to 442 and in the 2019 Lok Sabha polls, that number went up to 472—88% of the people’s representatives were worth Rs 1 crore or more.

This, however, has not always been the case. A CSDS-Lokniti study in the late 1990s had shown that high spenders in elections sometimes lost because of the revulsion associated with high spending, points out political scientist Shastri. He says that in the 1970s and ’80s, various lobbies such as the liquor lobby, the mining lobby and the education lobby would fund elections. “What started in the 1990s was that people who represented these lobbies thought: why should we fund candidates, why do not we ourselves enter the electoral fray and be candidates?” he says.

According to Jagdeep S. Chhokar, a founding member of ADR, candidates who have money not only fund their own campaigns but also the campaigns of others. The 2019 CMS study found that a higher proportion of election expenditure was being made by candidates themselves. While some candidates are indeed funded by parties, the proportion of party-funded candidates, especially among bigger national parties, is on the wane, the study says.

The 2009 Lok Sabha elections were the first time that the House saw representatives with net worth over Rs 100 crore, when four such people were elected to Parliament. In 2014, that number went up to 14, which further went up to 26 in 2019.

Not a Good Idea

A paper published in 2014 by American political scientist Nicholas Carnes, titled The Cash Ceiling: Why Only the Rich Run for Office, said that the economic gulf between politicians and the people who they represent has serious consequences for the democratic process. Carnes’s study, which focused exclusively on polity in the United States, found that politicians from different economic classes have different views, especially on economic issues.

Anand Kumar, political sociologist and a former professor at Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), says there has been an increase in the role of global and national black money in elections.

“Elections no longer continue to be a mirror of society,” Kumar says. He had contested the Lok Sabha elections in 2014 from North East Delhi on an Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) ticket. He lost to popular Bhojpuri singer Manoj Tiwari.

Carnes’s study says Americans from different classes do not usually have harmonious views about the government’s role in economic affairs. “When it comes to things like minimum wages, taxes, business regulations, unemployment, unions, the social safety net and so on, working class Americans tend to be more progressive or pro-worker, and more affluent Americans tend to want the government to play a smaller role in economic affairs.”

Does the same thing follow in India? What is true of American politics may not be true for India, says Rohit Azad, who teaches economics at JNU. This, according to Azad, is because political parties in India may have a common understanding and no one usually disobeys the whip while voting on policy matters, which is not the case in the US.

However, Azad adds, “A person’s wealth status can influence policy, especially on what they call ‘populist measures’.” What may happen, according to Azad, is the impact that relatively richer candidates might have on its policy positions, especially concerning the vulnerable sections of the society. A way around the rich versus poor candidate problem could lie in an overhaul of political party functioning in India. How about a party electing a candidate and not nominating. “If they are elected by members of the parties, they might not have to spend as much,” says Chhokar of ADR.

But democratisation of internal party functioning is not the only concern. “Money power is our biggest problem,” says Quraishi, who served as CEC from 2010–12. “We achieved what [the] media termed as [a] participation revolution but money power, I admit, is still a matter of concern,” he says. He suggests parties be funded by the state and banned from accepting private donations and calls for the creation of a national election fund where tax-free donations can be made.

For thousands of student activists wanting to enter the political fray, all of this might be a utopian. And the rising costs of elections may stop the poor from getting a seat at the table where the fate of 1.4 billion Indians is sealed. But an exclusion of the poor from the table will be a great loss for the “mother of democracy”.