In 2013, soon after his anointment as the Bharatiya Janata Party’s prime ministerial candidate, then Gujarat chief minister Narendra Modi pitched for a strong government at the Centre at a rally in Haryana. In his 65-minute-long speech, Modi described the Gujarat model of development as a prescription for the Indian economy that, he claimed, was in tatters.

Under Modi’s leadership, Gujarat’s gross state domestic product at factor cost had grown at a CAGR of over 17%. Modi’s call for a strong government at the Centre had an appeal in a nation going through a phase of what some called policy paralysis under the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government. Modi’s supporters seemed to buy into the argument that “policy paralysis” put the Indian economy in the category of fragile countries, a term coined by investment bank Morgan Stanley.

With Modi’s victory in 2014, corporate India believed that the era of coalition governments was over, which it blamed for India’s inability to implement further reforms needed to achieve its potential growth rate. While India had registered a commendable growth rate of 6.1% since the liberalisation of the economy in 1991, the achievement of the world’s largest democracy paled in comparison to the performance of the communist China that grew at an average of 10.3% in the same period.

Many observers argue that in 2014, a strong reason for Indian voters to rally behind Modi’s pitch for a strong government was to expect him to deliver an elusive double-digit growth rate to the economy. This could have made India stand up to its communist neighbour that regularly bullied it at the borders.

Close to nine years since Modi’s transition from Gujarat to New Delhi, the promised growth is nowhere to be seen. In fact, the narrative now has changed to India’s place in a slowing world, rather than the actual growth rate. This situation begs the question about the true potential of the Indian economy and if it is being held back due to political exigencies of whichever dispensation is in power.

Modi’s Queered Pitch

Living by his nurtured image of being a workaholic, Modi hit the ground running as soon as he assumed office and announced a stream of policy measures for a grounded economy. His supporting economists argue that if anyone has thought of carrying forward P.V. Narasimha Rao’s legacy seriously, it is Modi. His image as a reformist over the last eight and a half years, they argue, is dwarfed only by Rao’s, who took the vulnerable moment of the 1991 economic crisis to transform the Indian economy.

The policy reforms announced by Modi and his various ministers include the controversial demonetisation, the much-awaited goods and services tax (GST), Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), Ujjwala Yojna, Jan Dhan Yojna, consolidation of public sector banks and privatisation of loss-making Air India among others. The stock market has rallied behind Modi’s decisions, trusting his vision to transform an economy coiled in slumber, though his critics allege that the market rush is mostly driven by investments into companies that the government is seen endorsing. The Bombay Stock Exchange’s Sensex has given over 10% return to investors between May 16, 2014 and January 16, 2023. So far, this is the only perfect double digit story the believers of India’s growth under Modi have been told.

Despite the optimism of the Modi-endorsing economists around his reforms push, the economy’s average rate of growth has remained at just 5.5%. Even if we remove the Covid-19 year of 2020, reforms under the Modi government could provide India an average growth rate of 6.2%, a far cry from the double-digit growth that the country desires. India can take solace in the fact that China too is slowing down due to domestic and international pressure. It can be seen as a respite and opportunity for India on the widening trade gap with its hostile neighbour. It is important to note that like India, China also started losing the growth momentum rapidly in and after 2012 once the fiscal push provided after the 2008 crisis started wearing out.

Economic growth, however, is not a vanity project that matters in comparison with China. Growth is what will decide if and when India becomes a developed nation. Last year, Modi set for India the target of becoming a developed nation by 2047, the centenary year of India’s independence.

For a young nation, the goal to become a developed economy should look achievable. In 2020, India’s median age was calculated at 28.4 years. It is steadily rising and is at its highest now. India is likely to have a median age of 38.1 years in 2050 when its population will be around 1.63 billion. When Rao embarked upon his reforms, the median age of the country was just over 21 years for a population of about 88 crore. At 28.4, India is still considered young, especially when compared with China’s median age at 38.4 years. India’s working age dependency ratio—a measure of dependent people in the age group of 0–14 years and above 65 per 100 persons—is just 10 compared to 19 in China and 51 in Japan. Due to a young population entering the workforce, this is the window of opportunity for India. If the country’s economy is able to absorb its young working-age population, India’s per capita income is likely to achieve a level that can give it an entry into the elite club of nations in the high-income category.

However, India’s economic model has failed to produce the required number of jobs in the last two decades. Several studies suggest that economic reforms had started to fail from the time of UPA I government under Manmohan Singh. A study by K.P. Kannan, chairman of the Laurie Baker Centre for Habitat Studies, published in Economy and Political Weekly shows that India was able to absorb 57% to 58% of its incremental working age population between 1983 and 2005. This declined to just 15% during the next seven years ending 2011–12 and turned negative between 2011 and 2018, creating a jobs crisis in the country.

The story has turned worse post-2018, especially after the pandemic-induced economic shocks. As many as 12.2 crore Indians lost their jobs during the nationwide lockdown announced by the Centre to contain the pandemic in March 2020, according to data compiled by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, a private survey agency.

Politics over Policy

India’s inability to generate enough jobs in an economic model that kicked off in Rao’s regime has made economists question the logic behind sectors the governments decided to back. In hindsight, policymakers tend to argue now that the problem lies with the DNA of India’s growth story. In the 1990s, instead of focusing on manufacturing, it fell for the lure of the services sector, with a focus on information technology. Since decades of state-controlled economy had created a sizeable, English-educated middle class, it appeared to be a good deal for a country that was not growing fast enough to accommodate the aspiration of this class. Companies like Infosys, TCS and Wipro, which were just any other business entities till the economy opened up, became poster boys of India’s growth story.

In this period, foreign investors started to pour money into the Indian economy as well as stock s. But investing in stock markets is not the same as setting up industry in India. In a country where nearly half its working-age population is employed or under-employed in agriculture, land is seen as a cultural attachment as well as an economic resource. Convincing landowners and their workers to give up land for industry because the state wants to industrialise the economy was a tough task, especially when the industry expected the government to acquire land and offer it as a concession for generating employment. Successive governments since Rao’s time, thus, struggled to acquire land for industry. South Korean steelmaker POSCO had to pull out of a MoU after constant delays in land acquisition in Odisha in 2017. The project was the biggest foreign direct investment (FDI) for India in 2005, valued at nearly $12 billion.

Policymakers acknowledge this problem but are unable to get past it. “We were not able to implement critical reforms in land, labour and electricity pricing. Different governments tried in various ways but had little success. This put us at a competitive disadvantage in manufacturing, leading to less growth in employment than would have happened otherwise,” says Montek Singh Ahluwalia, former deputy chairman of the erstwhile Planning Commission.

The fiercely competitive nature of the Indian polity, which was meant to keep the executive in check on policy excesses, became the reason for policy flip-flops, making land acquisition, and at times major reforms, a casualty.

It is tempting to argue that politics trumps policy in India, and the expression “export-led economy” has taken too long to enter its political lexicon. This has had a devastating impact on India’s exports competitiveness not just against China but also other smaller Asian countries as well.

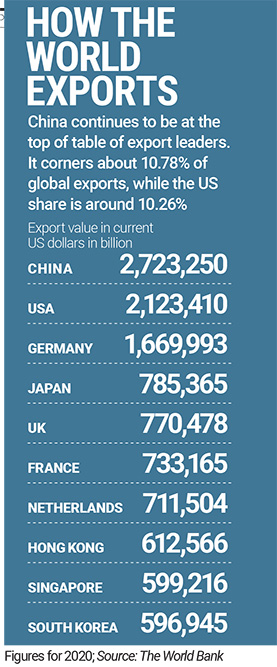

According to a research paper written by Prema Chandra Athukorala, published by Crawford School of Public Policy, Australia, “India’s share in world manufacturing exports increased from 0.6% in 1990–91 to 1.6% in 2010–11. Over the same period, China’s share jumped from 2.5% to 15.3%. By 2010–11, China was accounting for 38.5% of total manufacturing exports from developing countries compared to India’s share of 4.2%. The share of manufactured goods in total non-oil exports has continued to remain low (around 80%) in India compared to China and most other countries in East Asia.”

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) data shows that even though liberalisation led to high FDI inflow to India, the manufacturing sector got just about 21% of it as compared to 45% for services till the 2008 global financial crisis. The golden era of the Indian economy never returned, with the decade after that getting the moniker “the lost decade”.

Modi Covets India’s Chaebols

A decade is a long time to invest. There is nothing that the Modi government has not done for the organised private sector in the last nine years, from bringing in the IBC to enacting the GST law that eliminates smaller firms by way of increasing compliance cost for them. There was digitisation at the cost of fintechs and banks by making merchant rates zero. And, to top it all, the government announced a corporate tax cut in 2019, taking a hit of Rs 1.43 lakh crore on its revenue.

These supply-side steps attracted their fair share of criticism, especially from those who think the government’s moves are designed to hurt small industries, which incidentally address the employment concerns all over the country. Arun Kumar, a retired professor of economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University, says that the government has given policy benefits to the corporates. “The government has given huge incentives to the industry in the form of tax breaks and by making it difficult for the MSMEs to compete with the big industry by introducing GST. But the corporate sector has used those incentives to deleverage their balance sheets. The rate of investment from private sector is not going up simply because there is no demand in the economy. ... This capacity utilisation will not go up unless the government increases the purchasing power capacity of the people working in unorganised sector, which account for 94% of our total workforce,” he says.

Kumar argues that the growing inequity in India is the result of a shortage of demand in the economy, which was experienced even prior to the start of the pandemic when the economy was rapidly slowing.

But the government’s strong intervention in favour of corporate India was not good enough for it to increase its investment. Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s frustration was on display at an industry event last year. She said, “If it is not sort of impertinent to say this now, I equally would want to know from the Indian industry what is it that they are hesitant about even further? Since 2019, when I have taken charge of the finance ministry, I have been hearing the industry does not think it is conducive to invest … Alright, bring the rate down, the tax rate was brought down … Give production-linked incentives. We have given PLIs. I want to hear from India Inc., what is stopping you [from investing]?”

She does not seem to have received any informed replies to her question. Cut to Manmohan Singh when he exhorted India Inc to bring back the ‘animal spirits’, without much success. The questions remains: Is Modi making the same mistakes as MMS?

With FDI flow stagnating and private domestic investment not rising, the Modi government has discovered Plan B that suits it politically as well. The Centre is now relying on big conglomerates, like Adani, Reliance Industries, Tata and Vedanta, to carry the burden of large cap investments in its big infrastructure projects and capital-intensive industries, like green hydrogen, semiconductors and mobile handset manufacturing.

Over the last few years, big conglomerates have won most big projects in India. While these projects are awarded through a bidding process, the government support comes in the form of affordable land and other conditions that make competing with these companies impossible for smaller firms. So far, bigger groups have delivered on their promise. For example, without Reliance Jio’s disruption in the telecom sector—whose foundation was laid in the UPA era—India’s data usage would never have surpassed that of Western countries. That the government simultaneously lost faith in the state undertakings BSNL and MTNL is a side story of this development. Today, there are just two major players in the telecom sector, as against over half a dozen till 2012.

Similarly, the Adani Group, apart from creating ports and power plants, has committed investments in the green energy sector that can make India energy secure in the coming decades, while Tata and Vedanta are focussing on making India self-dependent in production of semiconductors. This model of attracting capital in the economy was used by South Korea, where certain chaebols, or large, family-owned business conglomerates, were given a free hand to dominate the economy. In return, those companies were expected to take risks by investing huge amounts of money in the economy in capital-intensive sectors.

In an article written in Foreign Affairs, former chief economic advisor to the Modi government Arvind Subramanian criticised this model of development. “The cumulative impact of the national champions approach could be more serious in India than elsewhere because Adani’s and Ambani’s conglomerates have interests that extend throughout the economy, in defense production, ports and airports, energy, natural gas, petroleum and petrochemicals, digital platforms, telecommunications, entertainment, media, retail, textiles, financial payments, and education.” He accuses the Modi government of “encouraging an extraordinary concentration of economic power” in the hands of “2As”.

Missing Investor Confidence and FDI

To understand how and why investor confidence in the India story started melting, a quick recap of the years preceding the global financial crisis would be helpful.

Despite the shortcomings of a services-led economy, India did well. Between 1999 and 2007, it posted a 7% plus growth rate six times. And then, the global financial crisis struck, dragging India’s GDP growth rate to 3.09%, the lowest since the 1991 balance of payments crisis. In 2009, the UPA government came back to power for a consecutive term, and to ward off criticism of giving a jobless growth in its first term, the Congress appointed veteran leader Pranab Mukherjee, who had cut his political teeth in a controlled economy, as the finance minister. Mukherjee was seen as the antithesis of his predecessor P. Chidambaram, who was considered pro-liberalisation and pro-corporates. Despite declining growth, government expenditure had gone through the roof due to the fiscal stimulus provided to the economy to avoid recession. Then there was the burden of the sixth pay commission which was implemented with retrospective effect from January 1, 2006. This took India’s fiscal deficit from 2.7% in 2007–08 to 6.2% of the GDP in 2008–09.

Mukherjee had wanted new sources of revenue generation to meet the rising expenditure burden. He introduced the retrospective tax law to challenge a Supreme Court judgement in favour of the UK-based Vodafone, demanding around Rs 7,900 crore in tax for purchasing 67% stake from Hong Kong-based Hutchison Whampoa. Ahluwalia was among the top policymakers within the government to advise against that adventure for raising money. But, the UPA government stuck with the decision of an adamant veteran politician of the party.

“The Vodafone decision, in my view, was wrong. In my book Backstage, I have said that I had advised the finance minister that it would be a disaster if it was done. More generally, I agree that policy uncertainty must be avoided. And judicial outreach is also a potential problem which can vitiate an investment environment. ... [T]he overall signal must be that the government will not resort to retrospective taxation and also that contracts entered into will not be cancelled. The judicial process must also be seen to be fair,” adds Ahluwalia.

The retrospective tax became a tool for the future governments as well. In 2014, Cairn Energy, a UK-based oil and gas firm, received a tax notice from the Modi government for capital gains made in a transaction held in 2007. While the notice was served by the outgoing UPA government, the new government under Modi pursued the same demand until losing a case in the arbitral tribunal in 2020.

Rajeswari Sengupta, who teaches economics at the Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, says that the successive Indian governments followed regressive tax policies following the global financial crisis to generate revenues and address the populist sentiments against corporates. “Be it retrospective tax issue or sending tax notices against industrialists, the message that the global as well as domestic community has been receiving is that India follows arbitrary policies, and the government can change laws any day. This arguably has continued to adversely impact private capex as well as FDI inflow,” she adds.

At one point, the government’s tax demands on corporates became so aggressive that corporate murmurs led to public outbursts. Celebrated industrialist Rahul Bajaj gave voice to these undercurrents of discontent within corporate India in front of the high functionaries of the government in 2019 at a public event. Addressing home minister Amit Shah, Sitharaman and railway minister Piyush Goyal, Bajaj said, “During UPA 2, we could abuse anyone. You are doing good work, but if we want to openly criticise you, there is no confidence you will appreciate that. I may be wrong, but everyone feels that.” His comments came a day after Modi’s predecessor Manmohan Singh had made a similar observation when he said, “There is a palpable climate of fear in our society today. Many industrialists tell me they live in fear of harassment by government authorities. Bankers are reluctant to make new loans, for fear of retribution.”

Closely linked to the fate of bankers is the IBC, which industrialists and foreign investors welcomed, as it had the potential to give them a swift solution to laborious legal processes in courts. However, it has become the new problem child.

“The adjudicating authority takes years at times to approve a resolution plan, which may become unviable in the meantime. However, the resolution applicant has no option to get out. Implementation of an unviable resolution plan may fail to rescue the company. It may even drag the resolution applicant into insolvency. A prospective applicant may, therefore, refrain from submitting a resolution plan to avoid such delay-induced risk. This inevitably dries up the market for resolution plans and, consequently, viable companies could be liquidated,” says M.S. Sahoo, distinguished professor, National Law University.

The government data shows that 73% of the cases filed under the IBC overshoot the 270-day deadline set for the resolution. In the case of Jaypee Infra, for example, the resolution process has dragged on for more than five years.

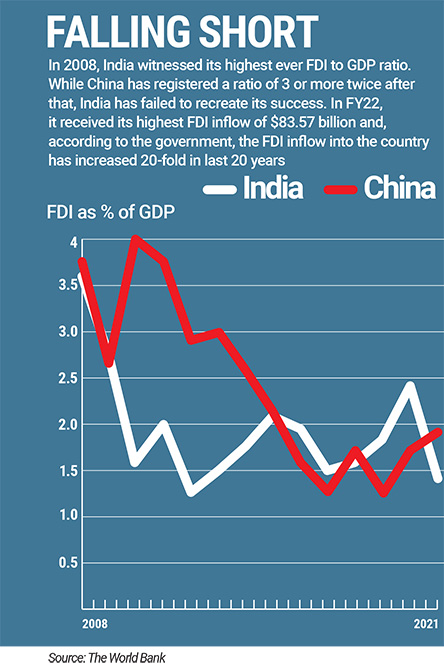

The World Bank data shows that between 2008 and 2021, despite India boasting of receiving the highest ever FDI each of these years, its FDI to GDP ratio remained at an abysmal rate of 1.9%. It is not just the FDI but also capital expenditure from the private sector within the country that has suffered over the last decade. Interestingly, the best years in this period were those when India’s GDP fell due to black swan events, like the global financial crisis and Covid-19. Sengupta observes that over the last decade both India and China have started becoming unpredictable with foreign investors. However, she adds, “while China has always been able attract strong FDI inflows, in India’s case, FDI as a share of GDP has been stagnating for nearly a decade, and this is bad news for us because in absence of a revival in domestic private investment, we badly need the foreign investment”.

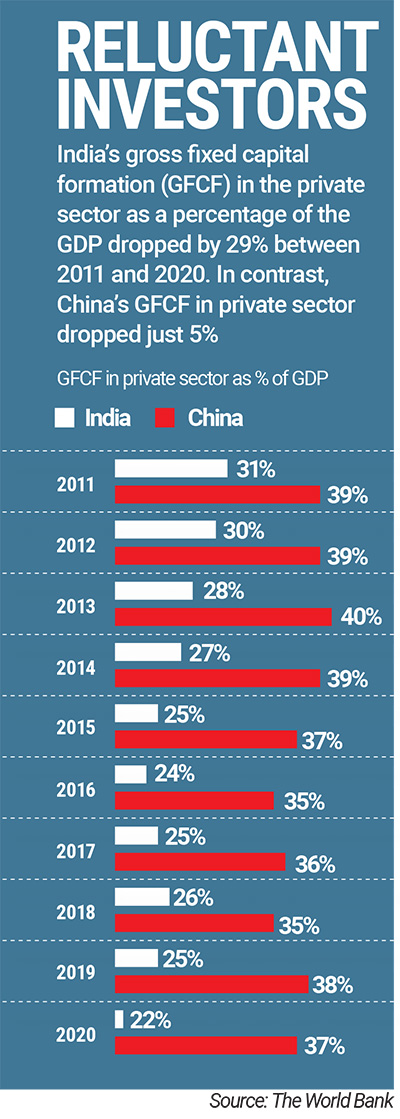

In the case of India, domestic capital also dried out from the market. Gross fixed capital formation from the private sector as a percentage of GDP came crashing down from 31% in 2011 to just 22% in 2020. This situation has forced the Centre to increase its borrowings and ignore high fiscal deficit.

To Manufacture or Serve

Even as the Modi government pushes hard to grab the China Plus One opportunity to make up for the misses of earlier governments and use the current geopolitics to its advantage, critics caution against the futility of this effort. Former RBI governor Raghuram Rajan has warned the Modi government several times against excessively spending its limited resources on manufacturing. From “The world does not need another China” to “India should invest in universities instead of giving grants under PLIs”, Rajan has made a strong case against the Modi government’s obsession to get its manufacturing right.

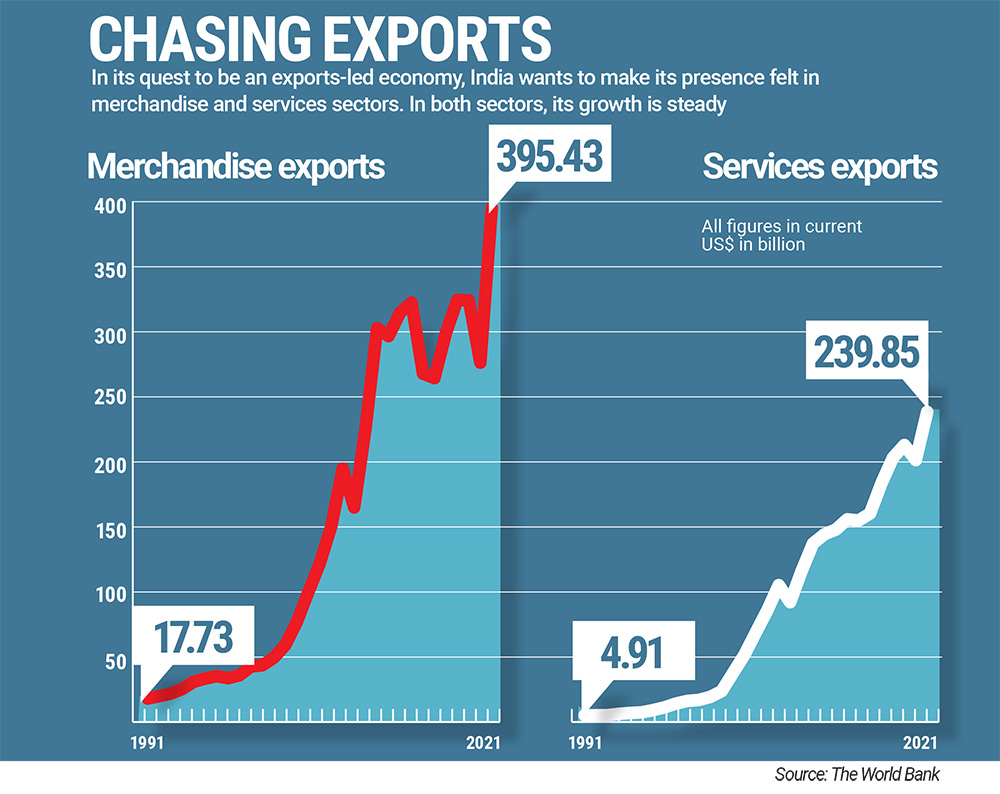

Data supports Rajan’s argument in favour of the services sector, which accounts for over 50% of India’s GDP as against a little over 15% for the manufacturing sector. In FY23, India’s services exports grew 28% in the April–December period, which becomes important in the context of the turmoil in the global economy. On the other hand, merchandise exports, despite all the incentives the government has offered, have grown by just 9%.

A new crop of economists is also beginning to mould the public opinion in favour of the potential of services in contributing to employment generation, which are traditionally seen as a high-skilled sector that creates rapid economic value but a limited number of jobs. Gaurav Nayyar, a lead economist with The World Bank, argues that in emerging economies, workers are moving away from agriculture and entering the services sector as manufacturing is unable to accommodate new workers. He says, “The share of the manufacturing sector in employment remained unchanged [in India] at around 11% between 1991 and 2018. As a result, much of the decline in the share of agriculture in employment was offset by the services sector. So even if, and when, the share of manufacturing in employment increases—greater industrial automation means that there will likely be fewer factory jobs in the future—services will remain important to India’s structural transformation.”

The supporters of Modi’s policies, however, point to the early success of the PLI scheme in the case of Apple to make a case for the manufacturing push. The company’s initial export figures for iPhone seem to have touched a figure of $2.5 billion already in FY23, according to a media report, though no official word is out yet. A government report on electronics exports, published in August last year, claimed that India was looking to export smartphones worth $8 billion to $9 billion in FY23, as against the $5.5 billion target achieved in FY22.

Critics of the PLI scheme argue that the scheme is expensive and promotes only the assembly of goods, and beneficiary companies will halt work at their assembly units the day the incentives are withdrawn. However, T.V. Mohandas Pai, a former director of Infosys, believes that PLIs offer the right kind of incentives for the manufacturing sector and address only 5% to 6% disadvantage that companies have when they manufacture in India. “Our lack of infrastructure and logistics facilities make manufacturing in India costlier by about 5%. The government is just compensating for that over a period of five years. This is a small share of India’s GDP and buys us time to work on these shortcomings in this period,” he says.

Though Pai has been one of the biggest beneficiaries of a service-led approach to economy as a co-founder of Infosys, he is a votary of manufacturing-led growth now. He argues that without a robust manufacturing sector, India cannot provide jobs to its youth and, hence, will never achieve its true growth potential. “It is a fallacy to say that in a labour-intensive country, only services can take us forward. There is no possibility of a country with a billion plus population to grow only on services. All countries where services are a large part of their GDP have become so after going through manufacturing and exporting [phases],” he says.

India does not need to look afar to see how a robust manufacturing activity can add to jobs in an economy and raise human development indicators. It has constantly lost market in the labour-intensive export sector of textiles to countries like Bangladesh and Vietnam. Data from research firm CRISIL shows that the share of the textile sector in total Indian merchandise exports declined from around 24% in CY2001 to around 11% in CY2020. In contrast, Bangladesh’s merchandise exports grew from $2 billion in early 1990s to $40.5 billion in 2018–19, around 84% of which was apparel exports. Bangladesh’s ascent from the category of least developed countries is ascribed to the dominance of textile exports, where a large number of workers are women.

The Centre has announced a PLI scheme for the textiles sector as well, but there is little enthusiasm for it, as the global slowdown and a competitive neighbour have taken a toll on this sector, putting pressure on domestic exporters. Moreover, the textile sector is scattered throughout the country and is dominated by small and medium enterprises (SMEs), which do not seem to be the primary target of PLIs and tax reforms push of the government.

The missing exports that Pai and others speak about need push in areas other than production incentives as well. Aradhna Aggarwal, professor at Copenhagen Business School, Denmark, who specialises in the study of global supply chains, is of the view that without focusing on intangible bottlenecks like corruption, the rule of law and robust institutions, India will find it hard to be competitive. “Every government gives incentives to promote manufacturing exports, but that is not the only thing required by the industry. Without quality governance, affordable labour and investor friendly institutions, India cannot attract foreign companies or even domestic companies to expand the scale of their manufacturing in the country,” she says.

Even as Modi launched a tirade against corruption and won elections by accusing the opposition of being corrupt, and despite being in power for close to nine years, India is ranked 85th among 180 countries on the global corruption index, as per the 2021 Corruption Perceptions Index of the Transparency International.

Growth between Bombast and Brass Tacks

With all these constraints, can India up its manufacturing game to generate an 8% plus rate of growth, if not 10%, in a de-globalising world? Karan Bhasin, a New York-based economist who recently co-authored a paper published by The World Bank on India’s poverty numbers with economist Surjit Bhalla, says that long-term growth requires an improvement in productivity, which, in turn, is based on investment in research and development and policy reforms. He says, “The quickest way to produce more is to increase the number of workers and machines (read as capital). However, there are obvious constraints on the ability of any economy to increase this number. In the context of India, we restrict the ability of land to move freely from agricultural to other more productive uses and this constrains our ability to grow at a higher rate.”

Bhasin cautions that factors beyond the manufacturing-versus-services debate impact India’s potential. He says, “In the past, India’s potential growth rate has been around 6.5%. During high global growth years, it has grown at higher or close to this level, while at other times, it has been a bit lower. With the new set of reforms, more up-to-date estimates suggest India’s potential growth rate to be closer to 7%.”

Despite PLIs and all sorts of reforms, he adds, achieving double-digit growth on a sustained basis is not possible at the moment, because a higher growth rate will entail incurring high fiscal deficit. “It will open up all kinds of macroeconomic imbalances, such as higher current account deficit, volatile exchange rate movements and higher capital volatility, which will subsequently create problems for the Indian economy and restrict it from enjoying a higher growth rate on a sustained basis,” he adds.

Rishabh Kumar, assistant professor of economics at University Of Massachusetts Boston, says that the economic reality of the world has changed post-Covid and, in the new reality, India does not need to grow at 8% plus. If China grows at less than 5% and India manages 6% plus rate due to the changing geopolitical game in the global supply chain model, he says, India will do just fine over the next two decades. “In current US$, India grew at 6.9% between 1991 and 2021. If the same rate is sustained between 2021 and 2047, India’s GDP per capita will reach $13,000—sending it to rich country status under current definitions,” he says, but warns that the cut-off for that status may change in the future and it assumes demographic, exchange rate and productivity parameters to remain favourable for India.

The world is in a state of flux that was last seen at the end of the Cold War. The Russia-Ukraine war, either as the result or the cause of this flux, whichever way one reads it, and impending recession in major Western economies have unsettled many a plan of policymakers all over the world. Just as US president Joe Biden announces more weapon support to Ukraine, no one can say for sure what this war will do to the global economy or how the global economy will settle the war. But economists know that the era of capitalist expansion that started with the fall of the USSR, which was based on a US-China trade bonhomie, has ceased to give returns to the West and is all set for a reboot.

This is a reality in which India is locating its place. India under Modi seems to have developed a three-tier formula for these years: let Indian chaebols dominate the manufacturing and services sectors for domestic consumption; let global marquee brands bring in FDI to help India increase its share in global exports; and, let the existing momentum in export-oriented services not be disturbed.

And, with this approach, the government would hope to attain a result similar to how Nayyar depicts China: “The rise of China as a manufacturing powerhouse often obfuscates its rising importance as an exporter of services. Given the growing complementarities between manufacturing and services, it is not surprising that China in 2005 was already among the largest exporters of professional, transportation and distribution services in the world.”