16 May 2017. The atmosphere at Delhi’s Taj Palace Hotel is electric. It’s the launch of the 2017 Maruti Suzuki Dzire and the buzz is worthy of India’s largest-selling sedan. Four cars are on display across two halls, there’s a wide stage for the presentations, and the created-for-the-event stands are filled with journalists, auto bloggers and young car enthusiasts. Even before Maruti Suzuki India MD Kenichi Ayukawa, engineering head CV Raman and sales and marketing head RS Kalsi take the stage to formally launch the latest version of the subcompact sedan, the scale and stretch of online discussions around the new Dzire means there are few surprises in store.

Still, once the event is underway, Raman and Kalsi field question after question from a young, informed audience: about the car’s reduced weight and height, increased wheel size and mileage improvement, as well as queries on Maruti’s electric strategy, since the government has indicated it will move towards electric cars by 2030.

The result: thousands of tweets and retweets, real time news updates, live feed, and answers to all possible questions that flow out of the room by the time the cars are actually unveiled. This new, improved Maruti launch event is a world removed from what it used to be in the past — but, then, the new Maruti customer isn’t like their previous avatar, either. “How one buys cars in India and who is buying cars has changed dramatically in the past five or six years. To ensure it stays relevant to its customers, Maruti has also changed,” says Kalsi.

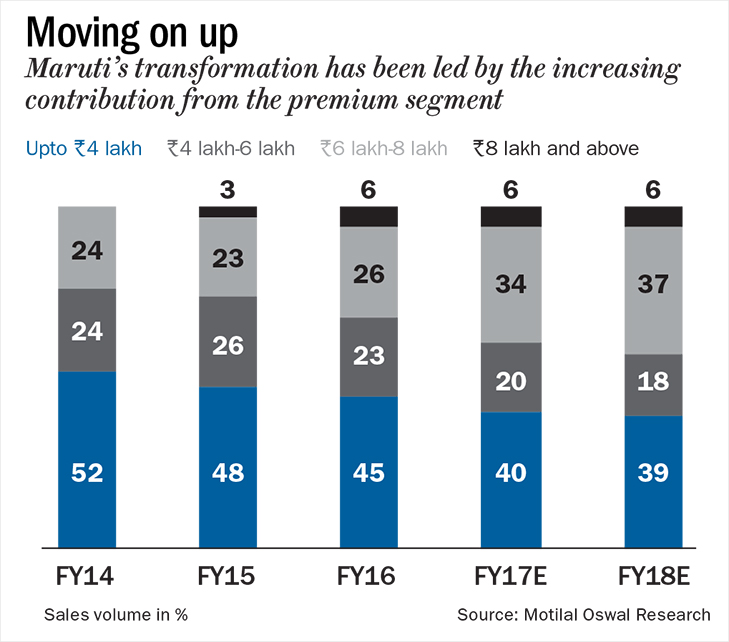

And how. In the past five or six years, Maruti has been consciously reinventing itself to remain competitive in a market where buyers are younger, more aware and have far more options than they did previously. The result? Market share is up 10%, the automaker once again rules across almost all segments, growth rates and margins are up, as is the average selling price, while discounts have come down. Over the past five years, sales has grown 93% from Rs.34,705 crore in FY12 to Rs.66,910 in FY17.Net profit, too grew 4.5x from Rs.1,635 crore in FY12 to Rs.7,338 crore in FY17. Maruti may have been the car your dad bought (and still favours), but it’s working hard to make sure it appeals to the new generation of car buyers, too.

Bumpy ride

Just about five years ago, it was a very different story. Market share had been steadily declining for over a year and in October 2011, Maruti was down to 40%, its lowest market share in a decade. Labour relations were at an all-time low, after an HR manager at the Manesar, Haryana, factory was killed by agitating workers in July 2012. Meanwhile, Maruti’s image of the fuel-saving and value-for-money carmaker was hurtling downhill to boring and meant-for-older-people.

What had gone wrong? Maruti Suzuki India chairman RC Bhargava recalls the doldrums period as an aberration brought about mostly by the policy environment. “Maruti has always been the market leader by a big margin; we lost market share only in FY12. Even then, it was not because we did anything wrong but because the government kept increasing the price of petrol, but not diesel. The gap became huge — from Rs.10 to Rs.30 a litre.” The price-conscious Indian consumer, Bhargava points out, was willing to pay extra for a diesel car, given the savings in running costs.

Primarily a petrol car manufacturer, Maruti was ill-prepared for the migration to diesel vehicles. In 2011, the company’s diesel engine capacity was just about 250,000 a year, compared with over a million petrol engines, and it didn’t offer diesel variants on its staple A segment models such as the 800, WagonR, Ritz and A-Star. But Maruti stepped on the gas quickly and, in 2012, set up a diesel engine plant at Gurgaon with a capacity of 150,000 a year apart from procuring diesel engines from Fiat. By 2014, it was offering diesel variants for most of its models. In 2013-14, though, government policy underwent another change and the gap between diesel and petrol narrowed again. This time, Maruti benefited, and sales of both petrol and diesel cars went up “We started gaining market share again,” says Bhargava.

More importantly, the policy flip-flop and its impact on market share acted as a wake-up call for the carmaker. Barring the first decade or so of its existence, when it was considered a premium product compared with the other cars in the market — the Ambassador and the Padmini — for the past 20 years, Maruti has very comfortably settled into the reliable, fuel-efficient, if stodgy and uncool, slot. Confirms ICRA senior group vice-president Subrata Ray, “Maruti’s perception for long has been that of an entry-level, affordable car.” High-end features, powerful engines and superior customer experience were attributes of other carmakers, not Maruti. Newer generations of car buyers, though, demanded all this and more, and the average customer age at Maruti was dropping, as it was with all car manufacturers. The average buyer is now 37 years old compared to 43 years old in 2010. “We took this as an opportunity to reinvent and prepare Maruti for the future,” adds Bhargava.

Make in India

At the Dzire launch, when Raman is finally done answering questions, he sits down to take us through the reinvention journey of the past half-decade. “Today’s customer is not looking only at the value proposition of kitna deti hai,” Raman points out. “Research showed us that they are also interested in all-round design, looks, comfort and convenience; safety features; digital connectivity; top-end entertainment systems. So, in all the vehicles launched after 2014, you see a change in how we have looked at vehicles, products or the consumer.”

For starters, over the past five or six years, Maruti has consciously moved up the value chain, with more launches in the mid and premium segments. Since 2011, Alto K10 (a variant on the Alto, launched in 2000) and Celerio (a hatchback launched in 2014) have been Maruti’s only new offerings at the entry level, while it has launched the Baleno (premium hatchback, 2014), Vitara Brezza (compact SUV, 2016), Ignis (hatchback, 2017) and Ertiga (MPV, 2012) in the mid segment, and the Ciaz (full-sized sedan, 2014) and S-Cross (mini SUV, 2015) at the upper end.

With its new offerings, Maruti has also upped its design game. The Baleno and Brezza, for instance, stand out for their sharp, modern look, safety and entertainment features. The Brezza also stands out for its dual colour options, the first of its kind in India. The Ignis, launched this year, has a tablet-like touchscreen on its dashboard that controls both navigation and the music system. Maruti is also offering ABS and airbags — premium safety features — even in the base model of new mid-segment cars such as Baleno and Ignis, as well as the Ciaz and SX4. “Currently, I am making vehicles for 2020, not today,” says Raman.

What is significant is that many of the new features and design improvements are being done in India. The new-found ability to develop products from India is the logical evolution of nearly 15 years of engagement between Maruti and Suzuki Japan. Indian engineers were regularly sent to Suzuki on two- to three-year-long assignments, to understand concurrent engineering which integrates design and manufacturing with other functions to reduce the time needed to bring a new product to market. Maruti’s first global product development participation was in the first-generation Swift whose product development started in 2002 and was finally launched in 2005. After that, Maruti engineers worked on the next-generation WagonR and, in 2008, did a full model change of Alto.

What was lacking was evaluation capability — vehicle, system, subsystem and component testing for all functions. So, all evaluation and judgements for Alto were done by Suzuki. Even that has changed. In 2012, Maruti set up a 600-acre R&D centre at Rohtak, Haryana, for in-house testing and evaluation. About Rs.1,900 crore has already been invested in the facility, with an equal amount to be further invested by 2019. The Rohtak centre was put to good use when the Vitara Brezza was developed here, the first Maruti vehicle to be designed, developed and validated in India. “Suzuki would have helped us if required, but we didn’t need their help. We just got the platform and engine from Suzuki and developed the vehicle here,” says Raman.

Brezza’s success couldn’t have come at a better time. The compact utility vehicle space has been seeing serious action for the past four or five years — competitors such as Renault, Ford, Hyundai and Mahindra were dominating the segment with their products (Duster, Ecosport, Creta and TUV300, respectively). Maruti was conspicuous by its absence in a segment that saw over 586,000 units sold in 2015.

Developing the Brezza in-house meant Maruti could make the product as India-centric as it wanted, while keeping in mind that the vehicle would be sold abroad as well. The vehicle was designed to fill a Maruti-sized gap in the compact SUV market. It worked — since its launch in March 2016, Maruti has sold over 120,000 units so far and there’s now a three-month waiting period. “Maruti has left behind several large players in the UV space. Mahindra used to be the big leader in UVs, but Maruti has been eating up their market share and M&M is finding it difficult to get back,” says Sneha Prashant, analyst at HDFC Securities who tracks the company. Indeed, from an over 50% share of the UV market five years back, M&M has dropped below 30%, while Maruti has grown from 16.1% to 25.7% in just over a year.

Going local

Increasing domestic involvement in design also means Maruti can increase localisation of components, helping it not only react faster to market requirements but also keep a tight lid on costs. “It isn’t a choice,” points out ICRA’s Ray. “In India, you cannot be cost competitive without localisation. Almost every OEM is going towards higher localisation.” While Maruti’s direct imports were a little over 4%, its vendors had significantly high imports of inner parts. Following the government definition of what constitutes imports in the case of component suppliers, then, painted a false picture: “It worked out to 25% in actual terms. We lost $1 billion a year, just because of the yen,” says Bhargava. Working with suppliers to help them localise was logical. Maruti developed incentives for vendors, created cross-functional teams across quality control and supply departments to focus on vendor development. Consequently, component import has dropped to 15% currently. “This 10% drop has saved us a lot of money. That’s why the share price keeps going up — because analysts like margins,” smiles Bhargava.

Selling an experience

If Maruti was to succeed at attracting a newer breed of car buyers for its pricier new models, it also needed to change the way it sold cars. “Moving up the value chain is a difficult task for anyone, especially if your brand positioning is entry level. Internationally, OEMs have dual positioning, which works well for them. Toyota has Lexus in the premium segment, Nissan has Infiniti, while Honda has Acura,” points out ICRA’s Ray. In India, though, the definition of premium itself is ambiguous — for some customers, he adds, a car for Rs.5 lakh can still be considered premium. Certainly, previous attempts by Maruti to go premium — with the Grand Vitara SUV in 2001 and the Kizashi in 2011 — had failed dismally. Given Maruti’s perception of being a value for money carmaker premium buyers would not go to a Maruti dealership to buy a Rs.10 lakh car.

Even the first version of the S-Cross, priced at over Rs.8 lakh, didn’t perform to expectation since customers felt S-Cross was over-priced for what it offered. Maruti learnt from its mistakes and came back with its premium offering, Ciaz which has done well.

But like Raman, Kalsi is a believer in market research. Maruti’s research had thrown up a fundamental difference between the current generation and its predecessor. “We realised that the youth is living for today and now, whereas the previous generation was focused on their future. And this generation is globally aligned and has refined tastes,” says Kalsi. And it was important to target younger customers because even if they weren’t buying directly, they were influencing buying decisions.

That meant Maruti needed to change its approach. “We decided that we have to focus on new products, new technology and a new experience,” Kalsi adds. The genesis of Nexa lies there — a premium retail dealership that would sell exclusive models and focus on the upscale selling experience. “The customer is willing to pay a premium for an experience. The world is fast becoming experiential. So we decided to offer a luxurious ambience and experience at Nexa,” says Kalsi.

It wasn’t easy for Kalsi and his team to convince insiders on the need for a new retail channel. Sure, their conclusion was backed by research but “internally, we had to get approvals; and we had to make presentations to Suzuki and our management. Everybody was worried that Maruti Suzuki’s strength lies in our reach,through our 2,000 outlets and Nexa could compromise that. After all, Nexa could never match that strength on its own,” he says.

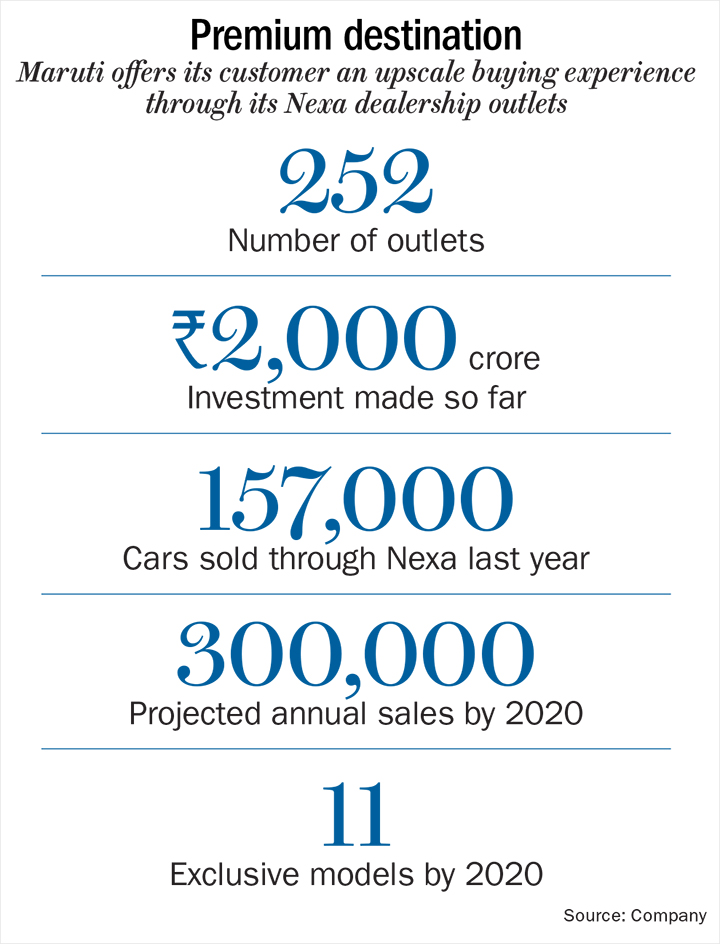

In 2015, the Nexa sales network was launched. To ensure current dealers didn’t feel threatened, Maruti decided to allot Nexa dealerships only within its existing network, to the best performers. The company currently has 252 outlets across metros, tier I and tier II cities, covering 90% of target customers who were potential buyers of premium hatchbacks and sedans. Meanwhile, the regular dealership network has grown from 1,100 in FY12 to 2,000 currently.

With two separate dealer networks, there is always the threat of cannibalisation, but Maruti’s worked around that by keeping the product portfolios distinct. Nexa sells only the new premium and mid-segment vehicles — and these models are available only through the Nexa channel — while regular sales outlets carry all other vehicles. Last year, Maruti sold 157,000 cars through Nexa, leading Kalsi to proudly claim, “If Nexa were an independent company, we would have been the fifth-largest OEM in the country.” The flip side: in 2016, Maruti and its dealers invested a staggering Rs.2,000 crore in Nexa and the channel started seeing traction only recently, with Baleno and Ciaz. Still, of the 15 new models Maruti plans to introduce by 2020, about six will be sold exclusively through Nexa. And Maruti aims for the new channel to provide about 15% of its projected sales of two million units in 2020, from about 10% of the current 1.5 million units.

Marketing makeover

That’s where a new, improved marketing outlook comes in. After all, setting up a plush new sales channel would be incomplete without upping the ante on the marketing front. “We realised marketing is no longer a linear activity. We switched to 360-degree marketing wherein we are engaged deeply in digital and BTL initiatives, and started doing high-engagement events,” informs Kalsi.

Given its current ambition, to be considered a premium carmaker, it’s not surprising that Maruti’s marketing initiatives are focused on Nexa. At the plush T3 terminal in Delhi, the company has created a Nexa lounge for customers, even if they are travelling economy. In addition to dedicated seating and hospitality services, the lounge also displays new models of cars sold at Nexa outlets. Another out of the box initiative is the Baleno Wicked Weekend. Started in September 2016, the plan is to have 40 such events in six cities, at popular party venues, with live music from well-known DJs and indie artists. Invitees are selected from applicants on the company website, adding to the exclusive image.

How effective have such tactics been? Says Puneet Gupta, director of global auto consultancy IHS, “In the past four years, Maruti has put in consistent effort in all functions, from engineering to marketing to sourcing. In marketing, especially, by enhancing the brand image through the launch of several good-looking models and the introduction of Nexa, it has been successful in moving B segment customers to C and D segment models.”

Future ready

The reinvention of Maruti is showing in the company’s numbers. But will the road ahead be smooth? Abdul Majeed, auto expert and partner at PwC, points to several challenges for Maruti. “First is new technology because, globally, several things are changing very quickly. Second, competition. Third, regulatory changes. And fourth, how will Suzuki Japan strike an alliance with Toyota, since Toyota, too, will be expecting something from Maruti in India.”

We’ll get back to the Toyota angle but first, take a look at how Maruti is making itself future ready on other fronts. Its biggest competitor is still Hyundai, but the Korean major’s volume is half that of Maruti. Rivalry will intensify with Maruti’s upscaling ambition but clearly, the company is banking on the Nexa network to give it an advantage over other players. The projected jump in volume, from 1.5 million vehicles to 2 million a year by 2020, seems reachable,given that Suzuki’s new plant near Hansalpur, Gujarat, came onstream in Q4FY17. That’s relieved the pressure on the older Gurgaon and Manesar plants, and newer models such as Baleno and Vitara Brezza are being produced from the new plant. With the addition of Hansalpur, which has an installed capacity of 125,000 units a year, Maruti Suzuki’s capacity has risen from 1.625 million to 1.75 million. The Gujarat plant is expected to reach 1.5 million units by 2030.

Meanwhile, Maruti has been opening its war chest regularly over the past couple of years — and will continue to do so — to buy parcels of land across the country. It has already bought an undisclosed number of acres at 77 locations, which the company will lease out in the future for setting up dealerships, True Value outlets (for used cars) and workshops and service centres. In FY18, Maruti will spend about Rs.1,500 crore on land acquisition and will invest to the tune of Rs.1,000 crore every year for the foreseeable future.

Bhargava explains the rationale: “A dealer today finds that a large part of his capital investment goes into setting up a showroom or an outlet. The cost of land over the past 35 years has gone up astronomically. If new dealers have to compete with the dealers who bought land at older rates, it will be a deterrent. Their investments will be so much higher but ultimately the car is to be sold at the same price at all outlets.” By providing land to its dealers, Maruti will be able to maintain stability in its sales network and, as Majeed points out, “It also helps the company establish better control over dealerships.”

It will also prove a competitive edge for the company going forward. Maruti is already well entrenched in terms of network, but this strategy will ensure it can readily expand its presence even 20 or 30 years from now. That will be especially handy if the much-touted conversion of two-wheelers to four-wheelers does finally happen in India. “Currently 3.5 million cars are being sold each year. But this number has the potential to go up 5x if two-wheeler owners start switching to entry-level cars. That may not happen soon, but you will need 5x the current network to handle that level,” points out IHS’s Gupta.

Japanese connection

Coming back to Toyota, Maruti’s parent Suzuki and the global car leader have been discussing a partnership for some time now. What will that mean for the Indian company? Getting technology has always been Maruti’s weakness — Suzuki has seen limited success globally in passenger vehicles (it’s world Rs.10 at present) and, unlike giants such as Toyota and VW, hasn’t had the resources or bandwidth for immense R&D. That may change. Bhargava explains: “Suzuki and Toyota are in discussion to look at new technologies in the area of environment. Toyota has the most patents compared to other OEMs like Honda, Hyundai and Nissan. Any new technology that is developed will come to us as well.”

His confidence isn’t misplaced. Suzuki has made it amply clear that India is top priority, and with good reason. The market now contributes 47% to the Japanese company’s annual profit and analysts expect India to become the world’s third largest automobile market by 2020 behind the US and China. It’s no surprise, then, that Maruti’s parent is doing all it can to ensure the carmaker takes pole position. The Hansalpur plant is owned entirely by Suzuki, which pledged Rs.8,500 crore when the project was announced; it has now committed to invest another Rs.5,700 crore in the plant by 2020. Bhargava sums it up succinctly: “Suzuki’s future is in India. And that’s only good for us.”