The ‘manic pixie dreamgirl’ trope was named in 2005. In movies, it is essentially a free-spirited, eccentric woman who rescues a responsible man from his boring life. Of course, it plays out as a love story that ends in a happy marriage, in which she supplies the spontaneous hugs and he ensures the bills are paid on time. On the big screen, opposites attract and make a cheerful home. Sadly, that’s not how the story is playing out between conservative Disney and relatively adventurous Star India.

The first got the second in a $71-billion buyout of Rupert Murdoch’s 21st Century Fox Entertainment, in a bid to inflate its library and increase its presence in the content business. The Indian operations add up to just $1.76-billion, but Star India, an established entertainment business in the country, is still an important piece in Disney’s global game. Despite its significant brand value, the house of Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck had no presence in one of the biggest growth markets even after trying for fifteen years. But Disney has since been trying to wrap its head around Star India’s style of functioning and programming decisions. What came as an unpleasant surprise for Star India was the disproportionate attention it would be getting. At least thrice a month, the top brass at The Walt Disney Company based out of Burbank, California get on a conference call with their Indian counterparts in Mumbai.

It is making folks at Star India anxious. They were accustomed to generous leeway until the buyout was completed last March. Disney asks questions, plenty of them, while the Murdoch family ran Star India through delegation and no more than a quick glance to check if all was well. The economic slowdown is not helping either, and senior management at the media house have been leaving in significant numbers. Uday Shankar, its chairman, was known to enjoy the trust of the Murdoch family and was the face of the company for years. Today he has limited interaction with the media. Outlook Business was not given access to him for this story, perhaps an indication of the transformation that is underway.

No fairyland

Disney may have won hearts with goofy mice and eager-to-please princesses but, in business, the company is a stickler for processes. A senior Disney official who spent years at its Burbank headquarters says the company is run like a bank with high levels of accountability. And this is its third attempt to crack the Indian market, so it won’t be kidding around. While the company has cracked other key markets such as China and Japan through motion pictures and Disneyland, among other things, India has always been described as a “black hole” in strategy meetings.

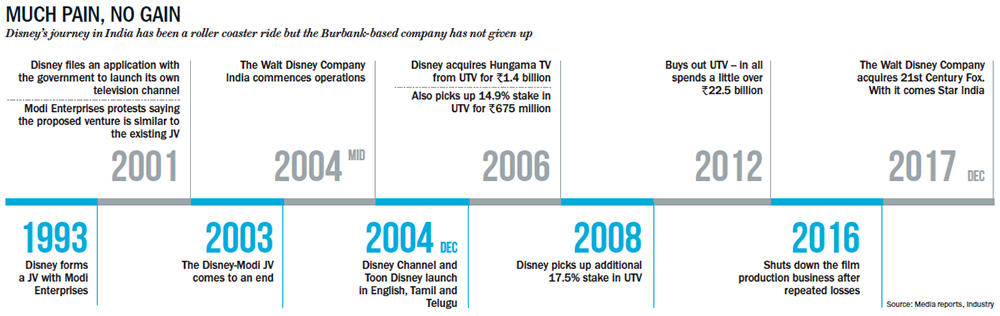

In 1993, to enter this market, they struck a joint venture with Modi Enterprises, but it came apart a decade later. In 2004, Disney launched two television channels preceded by the acquisition of Hungama TV from Ronnie Screwvala, and eventually his company, UTV Software Communications. Much as the deal to buy UTV was Rs.20 billion, an insignificant number for Disney, it ended in a financial mess and a complete overhaul of the business which included scaling down film production (See: Much pain, no gain). “It will be foolish to imagine that enough time will not be spent on India,” says a Disney official, adding, “Disney is obsessed about seeing its brand name everywhere.”

In 1993, to enter this market, they struck a joint venture with Modi Enterprises, but it came apart a decade later. In 2004, Disney launched two television channels preceded by the acquisition of Hungama TV from Ronnie Screwvala, and eventually his company, UTV Software Communications. Much as the deal to buy UTV was Rs.20 billion, an insignificant number for Disney, it ended in a financial mess and a complete overhaul of the business which included scaling down film production (See: Much pain, no gain). “It will be foolish to imagine that enough time will not be spent on India,” says a Disney official, adding, “Disney is obsessed about seeing its brand name everywhere.”

The company can be ruthless in its pursuit, and quick with its decision making. “It is a brutal organisation that will not think twice before letting people go,” says the former Disney official. According to another former Disney staffer, who worked at the US office, their way of working is “rather simple” — you commit to a certain revenue target and if you do not deliver, you are most likely headed to the door. “Every idea that comes will need to be backed up with a sound business plan. Disney is not an organisation driven by instinct and is generally risk averse,” he says while citing the example of Rich Ross, chairman of Disney Studios from 2009 to 2012. The going was smooth when under his leadership, the studio churned out global box office hits such as Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides, Alice in Wonderland and Toy Story 3. But it was all downhill from there when he also released movies that bombed — Mars Needs Moms and John Carter. “Ross assured the management that both would give high return and when they failed, he was asked to leave. Disney is the most fiscally responsible organisation in the entertainment industry,” says the same person. He recalls instances when a script would come to Disney and the management would raise questions about how they could monetise the content through all their products and services, be it theme parks or even lunch boxes. “They always make a clear demarcation between what is perceived as creative friendly and the need to be business friendly. Everything about Disney is driven by the bottomline,” he adds. Star India employees, on the other hand, were used to a more relaxed form of working and are already feeling the heat. In all, the Indian operation has over 3,000 people on its rolls, with 500 of them said to be on the chopping block.

Even Shankar seems to have been given a smaller mandate. Under the Murdoch reign, he had unfettered access to James Murdoch, the former CEO of 21st Century Fox. Today Shankar functions within a more layered structure. He has been re-designated as President (Asia-Pacific), overseeing businesses such as direct-to-consumer, monetisation, advertising sales, distribution and syndication. The studio business is another vertical, with consumer products and theme parks being the last one — each of these are split region wise with respective heads. Shankar’s new boss is Kevin Mayer, who is the chairman of direct-to-consumer and international division of Disney, who in turn reports to Bob Iger, Disney’s chairman & CEO.

Cricket googly

To the new boss at Star India, there are old mistakes to be explained. The big one is the media house’s overenthusiastic bet on cricket. In September 2017, in an audacious bid, Star picked up the global media rights for Indian Premier League (IPL) for a five-year period at a whopping Rs.163.48 billion. Sony had won it for a ten-year period starting 2008 for Rs.82 billion. The following April, Star’s then-parent, NewsCorp, approved its bid for BCCI rights (again for five years), making it the undisputed owner of cricket. Almost a billion-dollar bet, Star paid Rs.61.38 billion for these rights — 30% down payment and the rest over five years. All was well or so everyone thought.

Internally, the pressure began to build as the company had to salvage the investment and make it a profitable proposition. If Star believed cricket would draw advertisers, they were right but there was only so much the market was willing to pay.

Industry trackers find it hard to recollect a period when the sales team at Star was as high-strung as they were at that point. “They were constantly calling advertisers and media planners to close deals. It was a culture one had never seen at Star,” narrates a media buyer at a top agency. The marketing head of a large FMCG major knew Star was in trouble when its sales team came pitching in early 2018 for that year’s IPL edition. “Till then, a 10-15% hike in ad rates was the norm and here they were asking for 40%,” he recalls. From Rs.700,000 for a 10-second spot, it had moved up sharply to Rs.1 million. A massive 20% increase in viewership was also promised, when the annual growth figure had been half of that when Sony aired the tournament. “It all sounded unrealistic,” he says.

Eventually, that IPL edition brought in around Rs.22 billion, much higher than the Rs.13 billion Sony made in 2017. Star’s proceeds included Rs.19 billion from advertising (Rs.5 billion from Hotstar) and Rs.4 billion from distribution. The spike was because the tournament was aired also on Star’s regional channels (such as Bengali, Tamil and Malayalam) and because it owned the production rights. These rights allow the network to place commercial breaks wherever it pleased, increasing advertising seconds. But profit took a beating in FY18, even as revenue increased.

The bombshell moment for IPL’s advertisers was when the viewership numbers rolled in. The marketing head quoted earlier said that a 20% surge in viewership did indeed take place, but in a band of viewers — more specifically, males in the 15-25 age group from urban India. This is a neat little trick. Viewership in cricket has traditionally been measured across all demographics but Star India decided to quote an increase in a particular segment. It was a bit like promising someone world peace and settling a quarrel in a small island nation — the promise had been diluted in the fine print. “It was obvious they had shifted the goal post,” says the advertiser quoted earlier. To boost viewership, matches were also aired on Star Plus and Star Gold. Buzz is that unsold inventory prompted the network to take that decision.

Meanwhile, the sales staff at Star India was facing the same pressure for cricket World Cup 2019 too, which started barely a fortnight after the IPL. The slowdown could not have come at a more terrible time. Mayank Shah, category head, Parle Products, says the IPL and general elections that year had already taken away a good part of the average advertiser’s budget. Star India had initially quoted Rs.2 million for a 10-second spot (matches where India was playing) but had to settle for Rs.1.2-1.3 million.

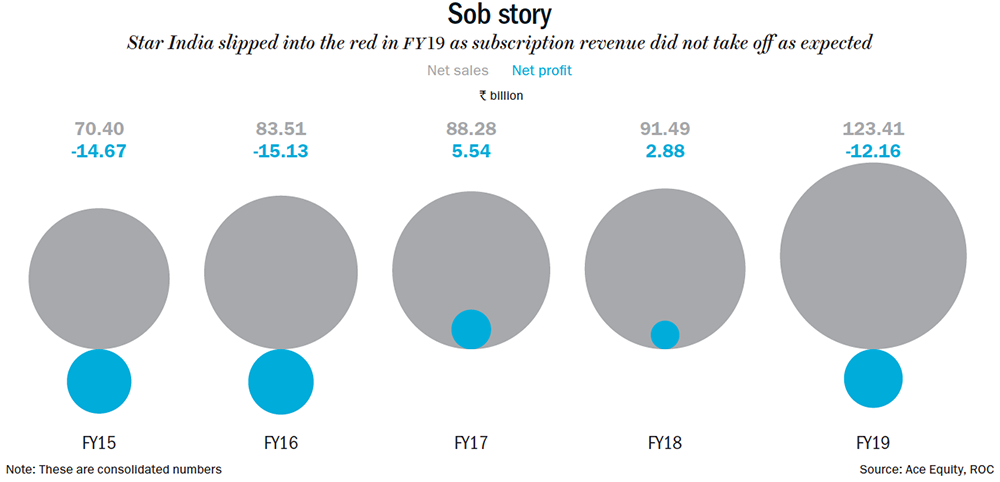

There was less money to spare with the advertisers and Star India had higher inventory with the World Cup’s 50 overs. The BCCI rights meant five days of 50-over test matches, where advertisers would not pay more than Rs.50,000 for a 10-second spot and Rs.300,000 for 50 overs. “At least the IPL bid made some business sense. The one for BCCI rights was driven by the impending pressure of valuation,” says RC Venkateish, ex-head, ESPN Star Sports (India and South Asia) and now founder, Lex Sportel Vision. In FY18, Star India had bagged a profit of Rs.2.88 billion but, in FY19, it slipped into deep red with a loss of Rs.12.16 billion, even as revenue increased 30% (See: Sob story). End June 2019 marked the first full quarter (Q1FY20) after the acquisition. It announced a loss of $60 million (Rs.4.25 billion), clearly rattling Disney’s top brass.

There was less money to spare with the advertisers and Star India had higher inventory with the World Cup’s 50 overs. The BCCI rights meant five days of 50-over test matches, where advertisers would not pay more than Rs.50,000 for a 10-second spot and Rs.300,000 for 50 overs. “At least the IPL bid made some business sense. The one for BCCI rights was driven by the impending pressure of valuation,” says RC Venkateish, ex-head, ESPN Star Sports (India and South Asia) and now founder, Lex Sportel Vision. In FY18, Star India had bagged a profit of Rs.2.88 billion but, in FY19, it slipped into deep red with a loss of Rs.12.16 billion, even as revenue increased 30% (See: Sob story). End June 2019 marked the first full quarter (Q1FY20) after the acquisition. It announced a loss of $60 million (Rs.4.25 billion), clearly rattling Disney’s top brass.

At the media house, there has been an exodus at the top level. Among these are Sanjay Gupta, country manager, Star and Disney India; Ajit Mohan, CEO, Hotstar; Gayatri Yadav, president (consumer strategy & innovation) and Amit Chopra, president and head (ad sales). Barring Mohan, who quit in September 2018, all the other exits have been over the past six to eight mwonths. Gupta is now Google India’s country manager, Mohan is VP and MD at Facebook India and Chopra is now the MD of Nature’s Essence. Yadav’s next move is not known yet. They didn’t even wait for their annual bonus payments, which usually comes in by August every year.

About the June quarter results, Disney’s spokesperson said that despite those numbers, “the key is Star/Hotstar has exclusive rights to a broad array of premium sports which will serve the company well over the next five years…The sports assets will continue to play a key role in driving the growth of Star and the subscription services of Hotstar in particular.”

Hotstar will clearly play a key role in Disney’s India plans while no clear path for Hulu’s entry into the country has been announced. The OTT platform that Disney owns in partnership with Comcast has gained popularity in the US due to its edgy content with originals such as The Handmaid’s Tale, Castle Rock, Catch 22 and others, but the company has restricted the app’s launch to only two countries so far, the other being Japan. The former Disney official in Burbank says Hulu will exist as long as there is a clear path to profit. In India, Disney is betting on Hotstar’s cricket popularity to make inroads into the Indian OTT space. On February 6, the Burbank management announced the launch of their OTT platform, Hotstar Disney Plus. It has to take on biggies such as Netflix and Amazon Prime. So, as arsenal, the parent has given its whole repository of Pixar, Marvel, Star Wars and National Geographic content, along with originals. But will that love be enough to carry them to a whole new world?

A little birdie chirps that if Star India’s whimsical ways have troubled Disney, Hotstar might just compound the misery. “You just have to take a walk from any floor in Urmi (the building in India that houses Star India) to the Hotstar office on the 26th floor to understand the difference in culture,” says a company insider. He explains, “Star is an analog, corporate and yet a pushy organisation but Hotstar is cool, brash and has little regard for hierarchy. It’s really a Silicon Valley tech start-up housed in a larger organisation.” Employees at Star India themselves are unsure what to make of its offshoot. “Anyone being asked to relocate to the smaller company recoils with horror,” says the Star India employee. The attrition level is 50%. But how can such a “cool” office be monsterville? A former Hotstar employee says Star has always been aggressive given the emphasis on sales revenue and “Hotstar is an accentuated version of that”. He adds, “It is extremely abusive with a pressure cooker atmosphere…it was conceived as the crown jewel of Star India.” In fact, even its valuation was benchmarked against a start-up in Silicon Valley. There was a sense of overconfidence about Hotstar’s valuation and its top brass claimed that it alone accounted for at least 10% of what Disney ended up paying for Fox’s entertainment business.

According to him, revenue targets border on unrealism. He lays the blame squarely on overpriced cricket rights. Even though it has been a cause of concern for a long time, it was never addressed. Shankar has been aloof to the idea of producing original content and is reported to have said, “Why do you need to produce original content when we have so much on our network?” The insider says Hotstar has been deemed as just one more screen to broadcast existing content. He adds, “That can never give us stickiness except when there is a big cricket tournament.”

The source also shares that at least 80% of its revenue comes from cricket and Hotstar has yet to create a robust revenue model in general entertainment. The OTT streaming service posted a loss of Rs.5.55 billion in the last fiscal, which was worse than the Rs.3.89 billion posted for FY18. The argument put forth has often been that it is still in investment mode (an estimated Rs.2 billion was pumped in last year). Mohan quit as Hotstar’s head in end-2018, yet the company (Novi Digital Entertainment) is yet to find a replacement. In a reply to Outlook Business, Disney’s spokesperson said that the company sees Hotstar “as a pillar in Disney’s direct-to-consumer business. Therefore, we are investing in content and talent and in growing the business long term”.

Besides the loss figure, Disney will also have to reconcile with Hotstar’s business model. In India, the biggest chunk of the OTT’s revenue comes from advertising (around 55%), with subscription and syndication (largely cricket content sold to Reliance Jio) contributing almost equally. In FY19, Hotstar had revenue of Rs.11.13 billion of which over Rs.6 billion came from advertising. In the Rs.70 billion advertising market for video streamers, Star India’s OTT is the second largest player after YouTube, which makes around Rs.25 billion each year. Other players with this business model include Zee, Sony and Voot.

But those who work at Disney say that the company is not comfortable with Hotstar’s dependence on advertising. The management does not think it is a scalable model. If ad or subscription revenue stay stagnant, the company could end up losing as much as 20% of the money invested for IPL rights. “If you look at Netflix or Amazon Prime, subscription is what determines their valuation. Disney’s focus will be to drive subscriber base,” says a former Disney employee who worked at the headquarters in Burbank. The studio did consider the advertising model during strategic reviews, but “Google and Facebook were taking away most of the advertising pie and it made no sense for us to pursue that model.” Disney was thus clear about taking the subscription route. The average subscriber of the OTT pays Rs.365 per year or around $5, and there are six million of them, so that translates to $30 million (Rs.2.10 billion).

Company insiders say the business plan assumed subscription revenue would increase 3x after the IPL bid was won. But that revenue has remained constant. “The ceiling on how much can be charged from the subscriber each month (fixed at Rs.19) has completely upset the calculation,” says an official. Today, around 35% of Star’s revenue comes from subscription, which is a little over Rs.40 billion. Added to that came the slowdown and advertising revenue dropped. The company was soon in the red. “In reality, it was a well thought out plan, but execution suffered because of external factors,” the official says.

For Star, this situation is anything but easy. It is stuck between a rock and a hard place — between Disney’s love for predictability and the pressure of delivering revenue, in the face of a slowdown. It’s a grim fairytale.