Permanent loss of capital is a thought that always keeps Pankaj Tibrewal on the edge. It’s not without reason, for the fund manager manages assets worth Rs.2,329 crore across mid-cap, emerging and balance equity funds at Kotak Mutual Fund. While the 38-year-old knows the importance of protecting the downside when it comes to investing, it has in no manner hampered his return scorecard. Tibrewal’s mid-cap fund has clocked a 44.32% annualised return over the past one year and 35.72% over the past three years. In comparison, the Kotak Emerging Equity Fund, which focuses more on smaller companies, has yielded a much better return — generating close to 46.95% annualised over the past one year and 40.13% annualised over the past three years. Tibrewal’s funds have significantly outperformed the benchmark indices like the S&P BSE Mid-Small Cap Index, which has given a return of 39.48% in the past one year and 27.83% over the past three years. In an interview with Outlook Business, Tibrewal speaks about his investing style and where the opportunity lies in the mid-cap space.

You have been managing the mid-cap, emerging equity and balanced funds for a while now, tell us how have you weathered Black Swan events such as the 2008 crisis or the recent demonetisation, which caused major upheaval in the market?

First and foremost, you cannot predict the future, at best, you can only prepare for it. In that sense, the one thing that keeps me awake at night is the fear of permanent loss of capital. I cannot predict if there is going to be demonetisation tomorrow or a 2008-like global recession. Last year, around this time, there was a scary situation. Because of the Chinese economic scare, crude, metal and emerging market currencies had tumbled. Equity markets, including India, too, were hammered. My focus is only on how to mitigate risks at the portfolio level and cushion it against such unpredictable events. I have to make sure that we can protect our capital in the event of a downfall, because if your capital gets eroded it will take very long for you to bounce back. But that doesn’t mean you don’t take risks. How well you can manage those risks will decide the outcome. That can only come with discipline and a process-driven approach. What I have learned over the years is that if your focus is on protecting the downside, returns will automatically be superior. My approach to managing risks is three-fold. First, the risk of permanent loss of capital, on its own, spurs you to scout for quality and, second, you need to know what are you buying and at what price. The company may be in a wonderful business, but is it a good investment? You have to buy at the right price to make superior returns. Finally and, more importantly, you need to know the downside risk. If you can control the downside, half of your job as a risk manager is done.

How does the risk framework look like at a portfolio level?

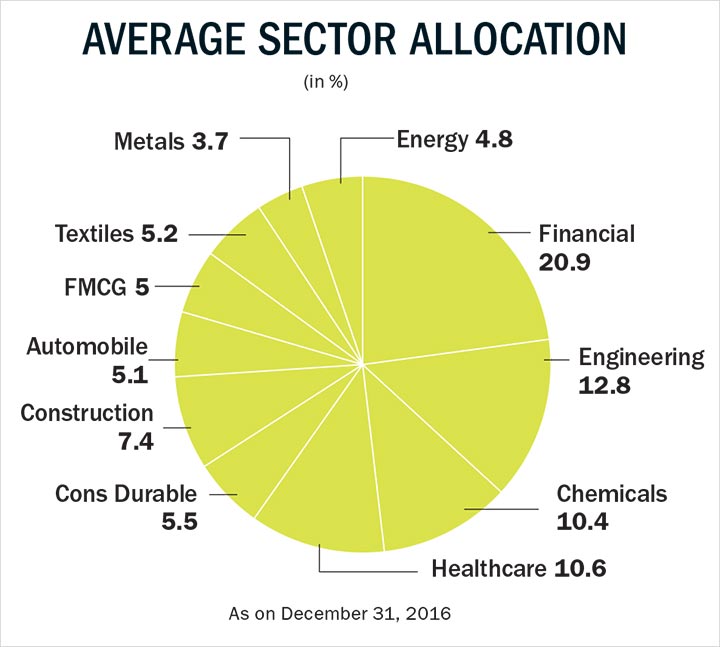

We look at concentration of portfolio, sectoral allocation, themes in the portfolio and how much you have in terms of domestic and global stories. For example, we have risk metrics defined for stock exposure and sectoral limits for respective funds.

How do you weigh quality in a mid-cap? What are the initial filters that you would start with?

The first filter is definitely the attractiveness of the business and the industry in which the company operates. This involves evaluating the company’s competitive edge: like its brands, distribution, product, technology and so forth. More importantly, you need to evaluate the sustainability of the company’s edge.

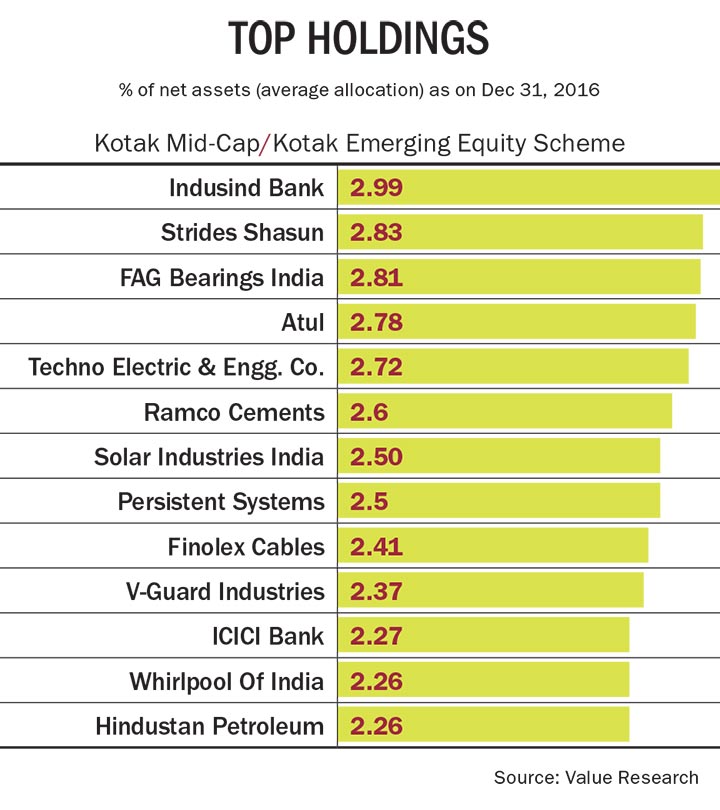

When assessing a company’s worth, the first and most important thing is to analyse its balance sheet and cash flow. If you want to gain real insight about a company, look at its balance sheet and cash flow. They give a clear picture of whether the company is making a real profit and how is the capital being employed. Cash flow will tell you the difference between the reported accounting profit and actual profit made. A company could be making accounting profit, but in reality it may not be generating any cash after taking into account working capital and related capex. This is precisely the reason that we stayed away from many industries such as infra, construction, real estate among others, which were the darling of the market at some point in time. Some of the companies in the mid cap space that met our cash flow and quality filters were Whirlpool, V-Guard, Finolex Cables, Supreme Industries, Atul, Ramco Cements, Motherson Sumi, Solar Industries and the likes.

But balance sheet and cash flow only tell you the past or, at best, the current state of affairs. To invest for the future and to assess the growth story, you need to think in terms of how future cash flows will shape up?

But balance sheet and cash flow only tell you the past or, at best, the current state of affairs. To invest for the future and to assess the growth story, you need to think in terms of how future cash flows will shape up?

Even to predict the future you first need to understand the past. When we meet the management we read up on at least five years of annual report to understand what the company is doing. When you are well read, the conversation with the management gives you a picture of where the company is headed. Let’s assume a company has inferior cash flow compared with other players in the industry or compared with the best in the industry; we will ask the management why the cash flow is inferior and what was being done about it?

Just as we project a profit and loss statement, we try and see whether the cash flow can improve further and can it be sustained in the future? Secondly, people get carried away with the momentum in earnings growth. But if that growth is coming at the cost of the balance sheet, the company cannot create wealth on a sustainable basis. Businesses that generate good return on capital are the ones that create wealth over a period of time. We try to avoid companies which can’t generate attractive return on capital employed on a sustained basis. We look for companies which are in a position to grow their return on equity or can sustain return on capital employed over a period of time.

How about a business which is going through a change but is plagued with low RoE, low cash flow and high debt?

The starting point for us to evaluate any company is that it should be generating return on equity of least 14-15% and if we see there is a scope for higher return on equity and cash flow, we get serious about investing. Let me give you an example. We bought India’s leading cable company in FY12 when it was facing issues owing to derivative losses. We met the management after a couple of years when they were actually coming out of the problem. We knew they had a strong brand and the industry had tailwind in its favour. When we met the management they said their first priority was to make the balance sheet debt free and gradually improve the company's cash flow and return ratios. The stock was then available at 8-9x one-year forward earnings. Over a period of time, the management delivered on its promise. As a result, the stock today trades at 20x one-year forward earnings. We made a 12x return on the stock in five years.

Today we have new businesses such as TeamLease, Thyrocare, Quess Corp and many others getting listed. But not all companies thrive, so how does one assess the quality of management?

Apart from the return on capital and attractiveness of the business, one very important aspect we need to understand is whether the people running the business are sharpening their competitive edge to deal with competition. To put it in perspective, look at the leader in the paints industry where people running the business have created a strong competitive edge. To test the durability of a management we look at how a company has behaved across different cycles. Has the company vanished after a bad cycle or has it emerged stronger? That is enough to give you a sense of a management’s bandwidth. If a company is able to weather a crisis or a downturn very well, it gives you an understanding of how the company is poised to do in different cycles. Companies such as Whirlpool, Bajaj Finance are few examples where we have analysed cycles in detail.

More than half of the so-called great companies of the past turned into mediocre businesses because they were not able to sustain their competitive edge or strengthen their moat. For instance, look at what happened to one of the leading FMCG noodle manufacturers after the crisis. The brand was so strong that they were able to come out of the crisis. You need to test the durability of a business which can be attributed to its brand, management and other factors that make it stay ahead of the curve. You need to ask if there are any emerging threats to the business. Is the management aware of these threats and what is it doing to deal with the same? But some companies are never able to come back and eventually vanish. Take the case of a leading telecom PSU. Till 2003, it was among the top 15 companies by market capitalisation. Today, it is steep in the red. The cash-rich company is now a cash-less company.

Given us an instance of spotting early a strong management running a sustainable business?

Given us an instance of spotting early a strong management running a sustainable business?

Let me give you an example of one of the largest retail oriented NBFC. About five years back, no one was talking about it. We used to meet the management of the company and were impressed when they used to talk about their MIS numbers. Even the product head or a regional head was aware of the RoA each product, each region or each branch was clocking. The level of precision was so high that it was evident that the retail business was not build on a shaky foundation. The stock went up 13x in five years. We saw a terrific management, potential for huge future growth and significant improvement in return ratios.

How do you manage to spot multi-baggers early?

You do not have to look for a multi-bagger. If your stock selection is right, you will end up buying multibaggers automatically. If you look at my funds and the stocks that I have invested, it’s amply evident that I am a bottom-up stock picker.

Can you give us an example of your bottom-up approach?

In 2013, when the US Federal Reserve hinted at a rate hike for the first time, the rupee started to depreciate, the market had crashed and people were talking about India’s vulnerability on account of external factors etc. Just about everyone was anxious. Around that time, we bought into one of the world’s largest home appliance company which has great brand equity and an equally strong presence in India’s growing market. The stock was trading at about Rs.170-180. The entire company, which makes close to 30% return on equity, was available at a market capitalisation of Rs.2,000 crore. Obviously the immediate earnings visibility was not there, but the company’s cash generation in the years prior to that was higher than the profit. That gave me the confidence that I am buying the Indian subsidiary of the world’s largest home appliance company for just Rs.2,000 crore. While others were fretting over visibility of earnings growth, my approach was that even if earnings did not come back materially, the cash generated by the company was so high that the investment made would automatically get rewarded over the next five years. We almost made 7x return on the stock in three years. It’s not without reason that consumer discretionary continues to be one of the biggest themes to play in India.

But buying cheap comes with its own set of problems. For example, IDFC has not really worked out for you?

IDFC was demerging its banking business into a separately listed company. Before the split we thought that the sum of the two businesses listed separately would be greater than the pre-split value. That did not work out that way as market did not give the anticipated valuation to the newly listed banking arm.

You appear to be overweight on cement and industrials

We are positive on the cement sector as it will be the key beneficiary of a capex revival. Companies have huge spare capacity as utilisation levels have fallen to around 65%. With no major capacity addition expected over the next three-four years, the sector is in a sweet spot. It will reap the benefits of higher operating leverage, better realisation and fewer supply constraints. If the capex cycle recovers, industrials will also do well. But within this theme, we are only playing early cycle companies engaged in bearings and ancillary products as they stand to benefit in the first leg of a demand recovery.

Earnings growth for the past four years has gone nowhere. What is your take?

In FY15, 78% of the Nifty companies saw earnings growth of 15%, but the remaining 22% (metals, PSU banks, some pharma names) proved to be drag. As a result, growth fell 1%. Similarly in FY16, 75% of the Nifty companies saw earnings growth of 15.5%, but 25% (PSU and private banks, telecom) kept the growth flat. In FY17, it’s the same story. The only difference is that only a handful of Nifty companies are proving to be a drag. Hence, the headline earnings growth should be around 8-10%. In the third quarter of the current fiscal, earnings grew by 10.3%, but if you exclude three stocks — Tata Motors, Bharti and Axis Bank — the number looks robust at 20.5%. So it’s only a matter of time before the laggard sectors start contributing to overall earnings growth. We expect a strong 15-18% earnings growth over the next two years. Sectors that are yet to see a revival in earnings will benefit as operating and financial leverage improves. Currently, Corporate India’s profit, as a percent of the GDP, is one of the lowest at 4-5%. Over the next two years, we will see a rapid improvement in bottomline growth. Once demand picks up, companies, which are now operating at 65-69% capacity, will automatically see a positive impact on their profitability.

What will trigger this recovery?

Before the demonetisation announcement, we were growing at decent pace with both corporate and consumer sentiment at a high. To start with, we had a good monsoon last year, followed by the implementation of the 7th Pay Commission recommendation. Once the impact of demonetisation wears off, demand revival in rural markets and impact of government spending will be evident. Today, interest rates are at their lowest, which is again a big positive for corporates to come forward and invest.

A good part of the discounting cycle is already behind us, so how are you viewing the market?

The market is a slave of earnings. In the interim, the direction of the market may not seem clear. But if earnings grow at a faster pace over the next two years, equities will react positively. Today, valuations may not be cheap but once the earnings cycle kicks in, valuations will start drifting higher, thus, giving a fillip to the market.