Dressed in a dapper Nehru jacket, Kishore Biyani took the centre stage at a jam-packed Ballroom at the Grand Hyatt Hotel in Mumbai on a Tuesday evening. The occasion was the unveiling of Biyani’s grand vision, titled Retail 3.0 — a 30-year roadmap on how he expects the Future group’s second innings in retail to pan out. In his opening remarks, Biyani sounded his usual self: blatantly ambitious. “It’s been 30 years since we started out and when we said what 2047 would look like, there was clearly an opportunity for us to be Asia’s largest integrated consumer business. I am being little arrogant in saying the word ‘largest’ but I will try to prove that,” quipped Biyani.

As the slides swept through the massive screen on stage, it was amply getting clear that Biyani was not giving up on his vision of being numero uno in retail despite having paid the price for his gargantuan appetite in his earlier attempt.

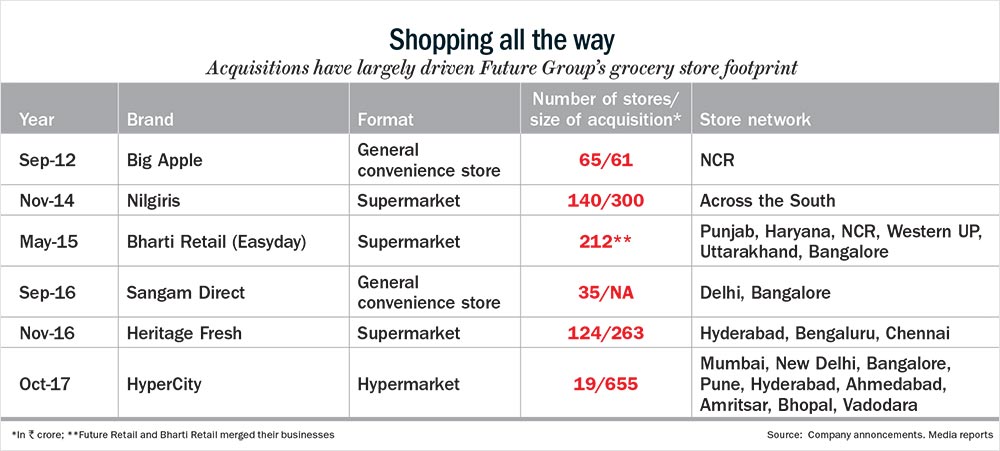

After making its presence felt in large format stores, Future group is now making a bid for dominance over the neighbourhood grocery store format, leveraging its existing network of 700 stores across various retail brands such as Easyday, Nilgiris, Heritage Foods’ retail business, Big Apple and most recently HyperCity, and opening at least 10,000 member-only relatively smaller stores across the country by 2022. As a first step, Biyani is looking to expand the Easyday network from 700 stores to 1,100 stores by the end of the current fiscal. That means, around 9,000 new stores would come up over the next five years at the rate of close to five stores every single day — though it’s not clear whether it would be organic or inorganic.

By any yardstick, these are ambitious targets, especially given that Biyani had burnt his fingers in the past by venturing into every opportunity that came his way — be it e-commerce, small stores or financial services. So, why is Biyani priming up for yet another ambitious odyssey, and what makes him so confident that it will work this time around?

Food for thought

To Biyani’s mind, his group is about much more than retail now — it is a consumer goods conglomerate, with brands across product categories such as home furnishing, apparels, fashion and food. “We can choose the format since we own our supply chain, distribution, retail network and consumer data,” he says. For Future group, then, retail is the conduit that supports the group’s consumer products, rather than the other way around. At present, Biyani has a portfolio of 27 brands under 64 categories — driven by group company Future Consumer — which includes private labels such as Kosh, Desi Atta, Karmiq and Golden Harvest, as well as those launched through joint ventures with Bin Ablan for premium bakery products, Hain Celestial for organic products and Mibelle for personal care products and acquisitions (Baker’s Street and Nilgiris).

That’s where the small stores come in. Biyani believes there is scope for over 10,000 “Dubeyji ki dukaan” — how he refers to the neighbourhood grocery, or kirana, by 2022. Over the past five years, Future group, through the acquisitions of Easyday, Heritage Foods, Nilgiris and Big Apple, built its network of 700 stores in the 2,000-2,500 sq ft range (See: Shopping all the way). Each of the acquisitions has a strategic locational advantage. Heritage and Nilgiris have most of the South covered, while Big Apple is strong in Delhi and Easyday brings in Punjab and a little from the rest of the North. “Easyday is definitely our biggest bet,” says Biyani in an interview with Outlook Business. The Easyday stores will have an enhanced product assortment with an average of 3,500 stock keeping units. “About 70% of what is sold will be our own brands and the other 30% will come from large companies. The investment for each store will be around Rs.15 lakh,” mentions Biyani.

The members-only stores will have a maximum of 2,000 members. Each member would be charged Rs.999 in annual fee which would entail them to a 10% discount on all purchases. “It will give us assured business and there will be no need to spend on advertising, which will reduce our operating costs as well,” explains Biyani. Under the membership programme, product assortment will be decided by the members. “This will be a unique model where they will decide our product offerings. A lot of business will be driven by data, with our brands delivering higher margins,” he says.

Biyani says the current average spend of members of Easyday is around is Rs.40,000-50,000 per annum and expects at least 50% of the members, which is around 10 million, to have an average spend of Rs.100,000 per annum by 2022. While rising income levels is expected to result in higher consumer spend, much of this increase will also be driven by inflation.

While the opportunity is large, the business is one that is tough to execute. No one knows it better than Biyani himself. Future Retail was a loss-making entity until restructuring in 2015 got it out of the woods. Post restructuring, all the retail infrastructure has been moved to group company Future Enterprise. It will also house the supply chain business, insurance business, cross holdings in listed group companies and Future Consumer, leaving Future Retail only with the retail operating business and a presence across multiple formats.

Post its acquisition of Easyday, Future Retail’s focus has been on cost reduction and closure of loss-making stores but the turnaround of Easyday is still underway. While the company has figured out the larger format stores with Big Bazaar, trying to crack the small store format has been harder.

This isn’t Biyani’s first foray into smaller stores either. In 2007, he started KB’s Fairprice, 400-550 sq ft non-airconditioned stores that sold basic provisions such as grains, onions, potatoes and the group’s private labels such as Tasty Treat. At the peak, there were some 200 Fairprice stores across Delhi, Mumbai and Bengaluru, but the experiment was not a success — Biyani couldn’t spend much time on the business since all his efforts went towards managing the burgeoning debt burden and all stores have since been reinvented as Easyday outlets.

Dippankar Halder, former CEO of Wadhawan Retail, which owned Spinach, Sab Ka Bazar and Sangam Direct, says the two most important factors that are critical for success in the small store format is having an efficient supply chain and managing store level operations. “If that is done, volumes will kick in and margins will be taken care of. Opening a store is the easiest part, but it is difficult to keep it open and even tougher to make money,” he explains. Traditional retailers have struggled because high real estate costs eat significantly into the viability of the business. In fact, high real estate costs have hampered most of the expansion plan of retailers. Future Retail is also likely to find it equally challenging to reach its target of 10,000 stores because finding that kind of real estate inventory at a viable cost will be difficult. The small format stores operate on wafer thin margins. The thumb rule for the small box format is to have a gross margin of 18-19% with store expenses taking away 12%; effectively, at the store level, a 7% margin is required to remain afloat, which comes down to a meagre 1.5% at post-tax level leaving almost no room for error.

What do competitors think of the neighbourhood store format? Says Neville Noronha, CEO, Avenue Supermarts, the parent company of DMart, “The kirana model is nimble and focused on convenience. We do not have the core competency to run a small format store to compete with the kirana model; our model focuses more on value. It is challenging to deliver value in the small format business.”

Also, pushing private labels, too, may be easier said than done. “The private label approach works in segments such as rice and dal where there is limited number of brands; and it will surely offer high margins here. But in categories such as dairy, where consumers are more familiar with brands, it will be hard for private labels to make a mark,” says Halder. That’s a view echoed by Abneesh Roy, senior vice president, Edelweiss Securities. “Fashion generally offers higher margins and that explains why private labels have worked well for many players,” he says.

In FMCG, however, the risk of failure is much higher simply because brand loyalty still exists. “Brands are more important in FMCG than fashion,” he says. At the same time, Roy explains why private labels are such an attractive proposition: globally, brands bring in the footfalls, while private labels offer the margins. “The latter has very little advertising and manageable distribution costs. If well managed, which is the challenge, margins can be twice as much as what brands offer.”

But this time around, Biyani is banking on technology to get things right. For one, the new stores will be opened with help from Google which will identify store locations by mapping consumer density. Future has also tied up with Facebook to drive social engagement with its consumers. The brick and mortar store will allow consumers to order on Facebook messenger, WhatsApp or through its voice app. Future has partnered with some start-ups in the areas of chatbots, machine learning and voice recognition. Future Retail is betting on data analytics to provide insights into consumer behaviour and buying patterns which will help them manage inventory better and replenish stocks ahead of time. According to Biyani, under Retail 3.0 where a technology layer is added to the brick and mortar stores, the cost of operations would be the lowest at 7-10%. The technology integration has already been tested in 350 Easyday stores in Punjab and NCR with 500,000 members.

Biyani also speaks of the “uberisation of the small-store business”, where his group can be the aggregator for others. Easyday will cater to every need of the consumer. For instance, if a consumer asks for five items and the store has only three, Easyday will use technology to see where the other products are available. That will be delivered to the consumer, either at his home or at the store.

That said, the contours of the small box business have changed significantly. Most large cities such as Hyderabad, Chennai, Ahmedabad and Bengaluru have their own retail chains with 15-20 stores at key locations. Local chains such as Ratnadeep in Hyderabad or M K Ahmed in Bengaluru will prove extremely feisty competitors, even as DMart opens large stores covering a large catchment area — it is already present in 41 cities. There’s also increasing competition from online shopping. While Amazon and Big Basket are gunning for a chunk of the standard grocery business, even players such as DMart have jumped into the fray — the chain offers online shopping, where consumers can choose between home delivery or picking up their purchases from designated locations near their homes. But Biyani isn’t too worried just yet and believes that his latest offering has the best of both worlds making it a winning combination.

Halder, recalls meeting Biyani at The India Retail Forum event in the end of 2005. At the time, Spinach, a neighbourhood store format, was close to opening its first few stores. “During our conversation, he said, ‘Chhota wala dukan nahin chalega (Small kirana stores won’t work). We, on the other hand, believed it was here to stay only because people would not want to travel,” says Halder. Narrating that incident today, Halder, who later moved to Easyday before becoming an entrepreneur, believes Biyani has demonstrated a certain flexibility today to take a fresh look at the small box format, which he was not convinced about earlier. But then, retail is an industry where the goalposts are constantly shifting and players who are too rigid about strategy inevitably lose. In the decade since Biyani and Halder had their conversation, the industry has seen the demise of the 1,600-store strong Subhiksha chain, biggies such as the Aditya Birla group reduce focus on More and Mukesh Ambani switching to clothes after Reliance Fresh found the going difficult. Next on the block was HyperCity Retail, a subsidiary of Shoppers Stop that operates large format stores. Future Retail snapped it up for Rs.655 crore in a stock and cash deal and has also taken on Rs.256 crore in debt on HyperCity’s books. This is the fifth acquisition for Future Retail. As a first step, Future Retail plans to increase the contribution of fashion sales across HyperCity’s 19-store network from existing 17% to 35% in the next one year. By reducing back-end and sales and distribution costs, Future Retail expects to improve gross margin by 3.4% to 27%.

The current consolidation scenario, led by Future, has left a limited number of players in the organised retail business. “A larger presence will give Future the advantage of economies of scale and help in deriving greater pricing power like what DMart has successfully managed. It is clear that the thinking is in that direction,” says Roy.

Changing tracks

The man on the street may recognise him instantly as the founder of Big Bazaar, India’s best-known hypermarket chain, but Biyani has always had an eye on fashion, right from the 1980s when he started off with apparel brand Pantaloons. In 2012, Future sold the Pantaloons retail chain to Aditya Birla Nuvo for Rs.1,600 crore, in a bid to reduce its Rs.8,000-crore debt. Selling his flagship business hasn’t lessened Biyani’s interest in fashion, though. Five years later, Biyani is back with renewed vigour and even greater ambition for the apparel business. “Today, we speak of wanting to be clothiers to the nation,” he says expansively.

There’s no doubt that the Pantaloons sale was the tipping point. “There was a feeling of having lost something after Pantaloons and that made us look for new opportunities,” he reflects. Now, Biyani is seeking those opportunities in volume, not just in food but also in fashion The plan, going forward, is to rapidly expand Future group’s fashion portfolio at FBB (short for Fashion at Big Bazaar), Brand Factory and Central, by not only opening smaller and more stores but also by simply selling more clothes.

Looking back now, Biyani says the Pantaloons sale was “a blessing” because it compelled the group to look closely at its other businesses. “I know what not to do as compared to the past. Today, there is a lot of focus on IRR (internal rate of return), which we never looked at earlier. If any project comes with an IRR of less than 35%, we do not go ahead,” he says. At the time, FBB was almost an afterthought: FBB was restricted to about 15-20% of the space at the 150 Big Bazaar stores and had just eight or 10 standalone stores.

The other two fashion brands, Brand Factory and Central, were housed under Future Retail but occupied opposite ends of the spectrum. Where Brand Factory was a discount store with less than 10 outlets, Central was an upmarket, multibrand department store format, competing with the likes of Shoppers Stop. “To us, it was clear that Zara and H&M could not clothe all of India. It had to be an Indian company playing that game,” says Biyani. The numbers also backed up Biyani’s decision to revamp the fashion portfolio. Five years ago, half of Big Bazaar’s came from food, home care and personal products, but gross margin was just 18%. In contrast, fashion accounted for 35% of revenue and had a much healthier 40% gross margin.

In 2013, the Future Group transferred its fashion business from its two listed entities, Future Consumer (housed the brands business which including Lee Cooper, John Miller, aLL, BARE and Indigo Nation, among others), and Future Retail (which housed Central and Brand Factory) into Future Lifestyle Fashions. Post restructuring, Future Lifestyles has grown to become one of the largest apparel retailers with a focus on brands as well as retail channels. With a total retail space of 5.5 mn sq ft across 90 cities, it has a diversified portfolio of over 40 brands across segments (men, women and kids) and price points.

Value conscious

Value fashion was the logical way forward from a business point of view, says Biyani. Now, FBB is the group’s vehicle for fast fashion, a concept used to describe low cost clothing in response to current fashion trend. FBB has an average MRP of Rs.375. “This price range is where India resides and for a young population, clothing is a very important part of their lives,” explains Biyani. The management decided that Brand Factory would shed the discount retailer tag and reach for a share of the aspirational middle class wallet, while Central’s positioning and value proposition would remain unchanged.

Once the strategic line was firmed up internally, the focus on FBB and Brand Factory began in full earnest. FBB soon occupied a much larger 40-45% of the area at each Big Bazaar outlet, with prominent signages indicating apparel’s new position on the ground floor, rather than one floor above. Brand Factory took the cluster approach, setting up four or five stores in a city before moving on to the next one. As volumes took off, and given Central’s prime positioning, the group could negotiate better deals with large brand owners and slowly lift the store above being a discounter.

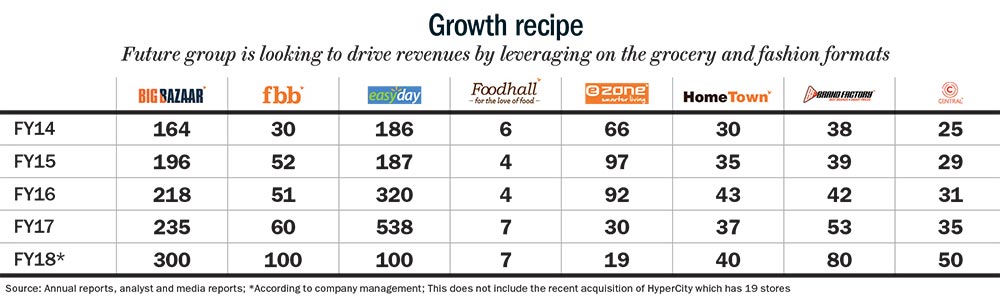

Currently, Brand Factory has 57 stores across 21 cities, bringing in Rs.1,000 crore as turnover. By the end of this fiscal, it would have grown to 80-85 stores, and to 200 stores by 2020. “It is now a store selling aspirational brands at a great price and not a liquidation channel any longer,” points out Biyani. FBB now has 60 standalone stores and will grow to 100 by March 2018; it currently has a presence in 250 Big Bazaar outlets, and will cross 310 stores by March 2018. Today, FBB, which forms 35% of Big Bazaar’s revenue, is a Rs.4,500 crore business of the total Rs.17,980 crore of Future Retail, the company that houses FBB.

The target is to have 1,000 FBB stores (standalone and shop-in-shop) in the next four to five years. Central, meanwhile, will add another 13 stores this year to reach 50 stores by March. In FY17, Central clocked a revenue of Rs.2,400 crore and it is expected to earn another Rs.3,000 crore-Rs.3,500 crore this fiscal. Almost 3 million sq ft will be added across formats in FY18. The overall investment for Future Retail and Future Lifestyle, which will cover all the formats, will be Rs.250 crore for the current fiscal. This will be funded through internal accruals.

But what took Biyani so long to look at the business through the lens of volumes? “I think we were conservative with respect to both these formats and that’s because we had too many things on our plate. Today, they are as important as Big Bazaar and Central,” says Biyani. In terms of structure, Big Bazaar and FBB are a part of Future Retail, which also houses Easyday, Foodhall, Ezone and HomeTown. Ezone will become a part of Big Bazaar, while HomeTown is in the process of being demerged and listed as a separate company. According to Biyani, the overall revenue for Future Retail and Future Lifestyle will be Rs.26,000 crore-27,000 crore for FY18, compared with Rs.22,000 crore for FY17.

The volume story

Future Lifestyle has been posting strong same store sales growth (SSSG) (average of 17.6% over the past five quarters) outperforming its peers led by better inventory management, better store layout, inventory liquidation and strong brands. A key component in Future group’s increasing fashion volumes has been about getting it right on supply chain and gaining relevant consumer insights from analytics. Rakesh Biyani, joint MD, Future Retail and the founder’s first cousin, says FBB was selling 60 million garments in FY13, seeing a modest 5-6% increase each year. A three-year horizon was then outlined, which involved more integration with existing vendors and having better ways to plan relevant assortment at the stores. The target was to increase the number of garments sold by 3x in 3-4 years. That year, a decision was also taken to do away with multiple warehouses and centralise all inventory at a single establishment, in Nagpur, Central India. This is in stark contrast to other apparel retailers such as Reliance Trends, which has three warehouses, and Max, which has eight. It has an area of 3.75 lakh sq ft. Earlier, Future had 18 warehouses spread across India. Nagpur was chosen because of its location. The approach is to reach “direct to store” from Nagpur and help comes from group company, Future Supply Chain. Biyani admits that there is a cost component but there are upsides — products reaching on time and logistics completely in control, that extracts greater levels of efficiency. “We now decided to replenish ahead of time and not wait for orders to come from the store,” says Rakesh. It is estimated that for every two pieces of garments that competitors have in their stores, Future’s stores have between eight and 10. The idea was to ensure there are no stock outs and reduce the number of trips.

Consumer feedback and research are also being given top priority. Using consumer insights on styles and the group’s new strategy of flooding stores with stock is working to FBB’s advantage. Rakesh points to men’s shorts as an example. Till last summer, FBB sold about 400,000-500,000 pieces of men’s shorts. The consumer insights team believed there was a larger market opportunity since empirical evidence pointed to more men wearing shorts frequently during travel and even on flights. “We probed a little more and based on our own information from consumer buying patterns, we realised we could sell at least 2 million pieces. We filled the stores and eventually managed to sell 2.8 million pieces this summer,” he says with a wide grin. Currently, FBB sells 200 million garments a year and Rakesh thinks that can increase three-fold in four years.

Those in the value fashion business agree on the growth potential. Vasanth Kumar, executive director, Max Retail, and one of the earliest players in the sector, says the penetration of organised retail for apparels was 15% in 2005, the year his company came in. “Per capita consumption then was three garments a year. Today, both the proportion of organised retail and consumption have doubled,” he explains.

According to him, the big change has been in the availability of better quality retail space, especially malls and a more aspirational consumer because of more awareness. “There is a very good chance that penetration levels will be at 50% in five years with consumption going up to eight garments per year. The opportunity will be a combination of clothing more Indians and clothing Indians more number of times,” thinks Kumar. FBB, Max and Trends together have a current turnover of over Rs.12,000 crore and other organised players such as Globus and Pantaloon bringing in another Rs.8,000 crore, taking the total size to Rs.20,000 crore. Kumar estimates this will double to Rs.40,000 crore in five years. Of the expected revenue of Rs.11,000 crore from the fashion business, Central is expected bring in Rs.3,500 crore, Brand Factory would bring in Rs.2,000 crore while FBB would make up for the balance. As one of the few companies in India which has a brand portfolio that straddles across price points, segments and distribution channels, analysts expect FLF to continue outperforming its peers both on the SSSG front and profitability.

Next on the list

Is Biyani being too ambitious with his grand plans for fashion and food? “There is nothing wrong about being ambitious. I just don’t want to be adventurous,” he says with a smile. Right now, he’s got a lot on his plate. Even if he using the acquisition route that has worked well for the Future Retail so far, getting to those predicted numbers will be a challenge. To even get to the target of 1,000 Easyday stores by end of FY18 in the next four four months will be a tall ask. Biyani insists things will start to look even more “interesting” once the small box story gains momentum. He strongly believes that this format will drive the next round of growth for the Future group. Meanwhile, he’s focusing on doing what he does best — understanding the mind of the consumer The underlying thought is to be always relevant and Biyani is betting on technology to ensure that. “If I am not relevant, the organisation is not relevant,” he says. There is no doubt that he will be banking on consumer insights like never before in the time to come. That could just end up making the difference between being ambitious and being adventurous.