When you need an answer to any question in the world, refer to Alice in Wonderland. It informs you that answers are overrated. Like when Mad Hatter asks Alice, ‘Why is the raven like a writing desk?’. The author Lewis Carroll later answered with “because it can produce a few notes… and it is never put with the wrong end in front”. So, when will the Indian economy recover? The Mad Hatter’s guess would be as good as ours.

What we do know is that the economy is growing sluggishly — gross domestic product (GDP) has shrunk for six successive quarters till September 2019 — employment is at a four-decade low and investment interest is weak. It does not make for a pleasant, tea-time chat but the pain is for real.

So, as part of our annual sentiment gauging survey, our reporters went to seven industrial clusters — Aurangabad, Surat, Ludhiana, Mandi Gobindgarh, Moradabad, Coimbatore and Tiruchirappalli — to ask SMEs about their performance in FY20 and what do they expect from FY21? Their answers mostly pointed to an economy in a churn, from which only the large and medium enterprises will emerge unscathed, maybe even stronger. The small and micro establishments will need to reinvent themselves urgently, even to survive.

So, as part of our annual sentiment gauging survey, our reporters went to seven industrial clusters — Aurangabad, Surat, Ludhiana, Mandi Gobindgarh, Moradabad, Coimbatore and Tiruchirappalli — to ask SMEs about their performance in FY20 and what do they expect from FY21? Their answers mostly pointed to an economy in a churn, from which only the large and medium enterprises will emerge unscathed, maybe even stronger. The small and micro establishments will need to reinvent themselves urgently, even to survive.

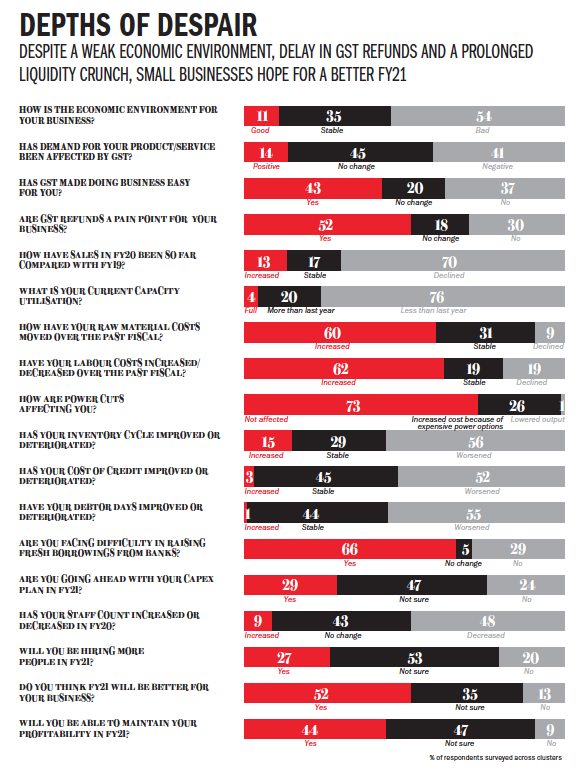

Of FY20, a large share of the respondents — 76% — said that capacity utilisation has been lower than FY19 and 70% said that sales have slowed down. Layoffs have become common; 48% have decreased their staff strength and only 9% raised it. Even historical advantage didn’t seem to be holding anymore, such as seen in Aurangabad and Tiruchirapalli.

In the past, any industrial town that has grown on the back of one large company or industry has managed to insulate itself from a slowdown. But, this time, all are equal in their misery. Aurangabad has grown on the back of Bajaj Auto and Videocon. With the consumer electronics major now in bankruptcy court, its vendors are livid and frantically trying to salvage whatever they can. For example, an entrepreneur with Rs.50 million in turnover is struggling to get back Rs.1.5 million that the company owes him. In the South, Tiruchirapalli’s fortunes have always been linked to state-owned Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited (BHEL) and, about six years ago, the situation started going downhill. Medium, small and micro enterprises (MSMEs) that have been dependent on the PSU — for passing on its extra orders or placing orders for its inputs, or were dependent on the PSU’s sub-contractors — saw that they were no longer relevant and needed. BHEL began getting fewer government power plant contracts, after it lost is preferential status in 2010 and it hadn’t upgraded its products such as power boilers. The smaller, dependent units are now not able to manage their working capital in this crunch.

It should come as no surprise that capex will not be easy to incur, and that’s not just in Tiruchirapalli or Aurangabad. Overall, 49% said that cost of credit has worsened in FY20 and 31% said that banks aren’t too keen on lending to them. Only a shocking 1% said that their debtor days have improved this year. So there are few who are willing to lend to the MSMEs but many clients who need credit.

Common concern

The hasty implementation of Goods and Services Tax (GST) has not helped cash-strapped companies either. “Lousy”. That’s how Shailendra Aggarwal, secretary, Indian Industries Association in Moradabad, described the implementation of the GST. He says this handicraft cluster’s revenue fell from Rs.80 billion a year ago to Rs.60 billion, thanks to this. His is a common sentiment. As many as 35% of respondents said that the GST has not made doing business easier. Only 13% found that demand for their product or services has improved after the tax rollout, while a much higher 39% said that demand has fallen. The transformation has been painful, they say. The new taxing system’s victims could be found in Ludhiana, Mandi Gobindgarh and Moradabad, where over 90% of the respondents said that they were not sure when their GST refunds will come through.

Say GST and Coimbatore would be the first to see red. Foundries here have had enough with the paperwork that has come with the new taxation policy. Senthil Kumar, founder of BlueMount Castings, says, “I am a mechanical engineer but operate like a chartered accountant. I’m constantly wondering which returns I have to file on which day, and in the process, get little time to help my company innovate.” This southern city has a culture of engineering genius. They did come up with the GI-tagged wet grinder after all. But, if they are being forced to work overtime (sometimes even Sundays, as one entrepreneur said) only to make sure all the dotted lines have been signed, then even inspiration withers. At the end of the day, there are higher tax bills to be paid even while the foundries’ debtor days are lengthening.

If the southern city is growing impatient with its recent troubles, it has company in Mandi Gobindgarh. This secondary steel cluster has been dealing with indifferent policymaking for long. Since the early 1990s, to be precise. That was when the government decided to encourage steel production and, for that, it made financing of enterprises easier and gave licences more freely. This landlocked cluster soon lost out to clusters nearer to ports. Overtime, it has had to deal with higher power tariffs and import duties on raw materials, and it has trudged on. Latest hurdle in its line of progress is the GST rollout. As Rajiv Sood, the president of Small Scale Steel Re-rollers Association, says, “It is a crime to own a business here. Micro and small industries are dying a slow death.”

Credit crunch

In the midst of this severe liquidity crisis, businesses are being forced to transform their processes. MSMEs have to invest in technology and in skilled labour that can use the technology. Unsurprisingly, units devoid of scale are finding it the hardest to make this leap. In Moradabad’s handicraft units, workers earlier only had to cut and weld. Today, casting skills are necessary as well but workers are not taught these at vocational training schools. Raghav Gupta, who runs the largest handicraft exporter in the cluster, called CL Gupta Exports, says, “Manufacturers have to train their employees, who then leave, and we have to start the whole process all over again.”

It’s the same story in Surat’s diamond manufacturing units. Smaller enterprises can afford to pay their staff only Rs.15,000 to Rs.20,000 a month. They lose their trained staff to the bigger facilities who pay double of that and even Rs.150,000 to a select few. In this cluster, there is also the influx of auto-polishing machines. Nikunj Shankar, director, Shivam Jewels, says, “Earlier, it used to take five days to get a diamond polished. With the machine, that has come down to two.” It is an impossible situation for someone like Rutul Moradia who runs a micro unit with about 30 workers. “Maybe we need to invest in technology, but where is the money to do it?” he asks despairingly. He has seen no business to speak of in the past three years.

The US-China trade war has not helped. Our giant panda neighbour imports 35% of Surat’s diamonds, which is then sent over to the US as finished jewellery. But until of late, the two were trying to stare each other down. So China has no need for that many diamonds and that means Surat’s Christmas sales was down 15%. This textile city is praying really hard for the trade war to completely cool down. Moradabad will beg to differ though. It competes with China in handicrafts sales, and the less for China is more for Moradabad. Neighbourly love can take a walk. Joginder Gandhi, who owns Dewan and Sons in the UP city, says that units in China that ran several shifts a day now only run till lunch time. Does he sound gleeful? He should. He “snatched” (his words, not ours) a deal from China seven years ago to make a batch of copper firepits. That order is still going strong.

Ludhiana would love to be in Moradabad’s shoes right now. It has to compete with the dragon too, in the global cycle market. India has 12% share of the market and Ludhiana makes 80% of India’s bicycle parts. Sounds like a good deal. Except, India comes a far second as an exporter when compared to China, which has 70% share of the global cycle market. Also, what hurts is that our neighbour easily dominates the high-margin segment of medium and high-end cycles. MSMEs in Ludhiana say that they could do well in these segments too, only if they had the right technology and materials.

No respite in sight

The general sentiment across clusters has been of struggle, and there is little optimism about FY21. Only 29% are going ahead with their capex next year, while 24% aren’t and 47% are undecided (which generally means “no”). Only 27% are planning to hire more people next fiscal, 20% aren’t and a good 53% are undecided (and you know what that means). More than half of the respondents are sure that the next fiscal will be good for the business, then again 13% aren’t and the other 35% are unsure (which reflects the same sentiment as undecided). Though 50% believe sales growth will be good, only 44% believe that they will be able to maintain profitability. For the SMEs, every day looks a bit more like the Red Queen’s race in the Carroll classic. As she explains to Alice, it will take all the running you can do to stay in the same place. To get ahead, you must run twice as fast. Nonsense, except when there is truth in it.