Kiki Challenge lost to dabbing lost to flossing. These dancing trends didn’t necessarily die out in that order, but if they had corpses, they would have piled one on top of the other. The head spins thinking how quickly things are becoming irrelevant. In this accelerated digital world, should you even try, if you are a brick-and-mortar anything?

This is the story of a brand that tried and is winning. Settle in, it is as comforting as a cup of hot chocolate on a winter evening.

Enter Croma. Well, it really entered the retail scene more than a decade ago. It opened its first store in 2006, as a retail chain run by Tata Group’s subsidiary Infiniti Retail. This was the beginning of modern retail in consumer electronics in India. Till then, we bought our televisions and washing machines from the neighbourhood store or the few multi-city chains such as Viveks and Vijay Sales.

There was no brand that went national like Croma did. “We were at the forefront of the migration of desktops to laptops, CRT (cathode-ray tube) to LCD (liquid crystal dis-play) and then LED (light-emitting diode) TVs, and phones to smart-phones,” says Ritesh Ghosal, CMO at Infiniti Retail (Croma).

E-commerce came to India in 2007 but it got aggressive only in 2012. Its sales went from $6.3 billion in 2011 to $14 billion in 2012, on the back of discounts and offers. This was also the year Croma was hoping for a turnaround. “By 2011-12, we had 100 odd stores and were on the verge of becoming profitable in spite of the emergence of numerous competitors in the offline space. Traditional electronics retailers had re-invented their showrooms and new competitors were opening shops; everyone managed to create showrooms that looked like ours, but none were able to match our selling process,” claims Ghosal. The retailer was riding a high just when online sellers entered the race.

“In 2012-13, the e-commerce marketplace turned its attention to our categories, especially smartphones. This created havoc for Croma,” he says. The websites solved the problem of price discovery at scale and did a decent job of comparing products spec-by-spec. “Yes, we did suffer a temporary loss of relevance when the e-commerce players first emerged on the scene with a larger assortment than a physical store could carry,” adds Avijit Mitra, CEO and ED, Croma. Sales from stores began to drop and losses began to mount year-on-year and Croma believes these new players affected their sales more than any other offline retailer. “By offering products at heavily discounted prices, often below cost, the e-commerce sites used investor funds to scale up their reach. Our pricing started appearing more expensive. Our strength became our Achilles’ heel in just a matter of months,” explains Ghosal (Outlook Business contacted leading e-commerce players in India, but none of them agreed to participate in the story).

“In 2012-13, the e-commerce marketplace turned its attention to our categories, especially smartphones. This created havoc for Croma,” he says. The websites solved the problem of price discovery at scale and did a decent job of comparing products spec-by-spec. “Yes, we did suffer a temporary loss of relevance when the e-commerce players first emerged on the scene with a larger assortment than a physical store could carry,” adds Avijit Mitra, CEO and ED, Croma. Sales from stores began to drop and losses began to mount year-on-year and Croma believes these new players affected their sales more than any other offline retailer. “By offering products at heavily discounted prices, often below cost, the e-commerce sites used investor funds to scale up their reach. Our pricing started appearing more expensive. Our strength became our Achilles’ heel in just a matter of months,” explains Ghosal (Outlook Business contacted leading e-commerce players in India, but none of them agreed to participate in the story).

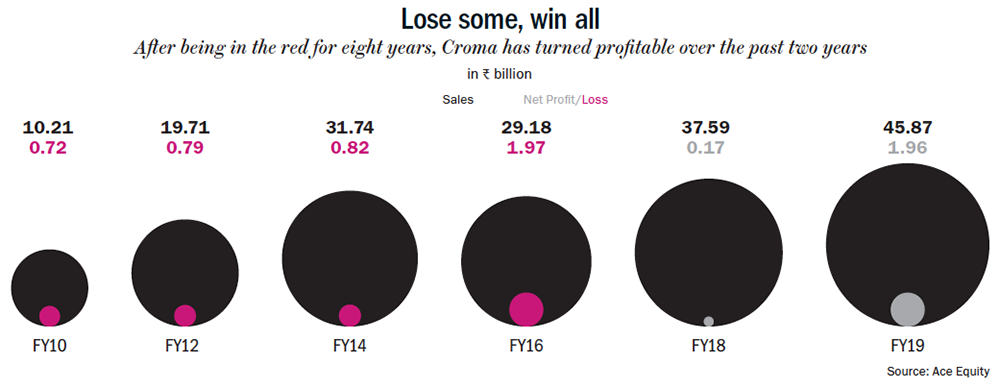

It would have taken out the best of us. To make a difficult climb and, just as we are to summit, have a landslide take us down. But the offline retailer decided to regroup and scale again. It has been a challenging task but Croma cracked it. Its footfall has grown by 3-5% in the past four years in stores that had seen a deceleration post-2012. The retail chain has managed to better its first-ever profit of Rs.160 million (FY18) to an impressive Rs.1.96 billion in FY19 (See: Lose some, win all). The topline has jumped 22% from Rs.38 billion to Rs.46 billion in FY19. “It’s an absolutely razor-thin margin (2-4%) business, where you’re constantly looking at how to keep the stickiness of your consumers alive,” says Ankur Bisen, senior VP (retail & consumer products), Technopak. “Many of their categories are browser-based (for which people research extensively online, such as smartphones and laptops), and there’s not much they can do beyond bundling of offers, better presentation and sales support,” he adds.

Ear to ground

Croma’s management started by watching customer behaviour in stores closely, and the research threw up interesting insights. “People were still visiting our stores to check out the product and verify what they wanted to buy before purchasing online — sometimes while standing in our store! We were helping people buy, just not from us,” says Ghosal. The edge offline retailers had over e-commerce websites, particularly in electronics and home appliances sales, was the need for physical validation before the actual purchase. That, for them, was the defining moment. The first step for Croma, therefore, was to empower staff on the shop floor. They had to know the ‘enemy’ well — they had to keep a track of the prices that online stores were offering, and their hidden costs and conditions. Based on this, the staff would then be able to make a good pitch to the customer explaining the cost difference. For example, if an air-conditioner is available at Rs.25,000 online and Rs.28,000 in Croma, it could be because e-retailers aren’t including good-quality wiring during installation or not offering installation at all. “The online seller may dilute the proposition and lower the price,” says Ghosal, adding, “in which case, the staff at our store explains to the customer why we have a different number on the tag.”

If there is a big pricing gap, say above Rs.3,000, then Croma renegotiates its price. It also gives out discounts on display items or last year’s models, and extends offers particularly to repeat customers. Mitra believes focusing on the customer was one of the most important strategies for their turnaround. Hence, price was not treated as gospel and made more flexible in line with e-tailers’ listings.“We got into trouble because we took our eyes off the customer and the way he was shopping. We regained our competitiveness by putting in place a rigorous ‘customer listening programme’,” he says.

Besides these, services that online stores struggled to offer — such as exchange offers, lifetime service and e-waste management assistance — were made available. Technopak’s Bisen acknowledges Croma’s move of playing to their strength. “Customers are not married to any single channel. They want convenience and the best value,” he says, adding that mom-and-pop stores still account for 65% of all electronics sales.

The shopping experience is another ace in their hand. Nilesh Gupta, MD, Vijay Sales, an electronic retail chain with 102 stores saw success with this. Two years ago, Vijay Sales launched TV commercials showing store managers serving customers with their expertise and warmth — something which e-commerce cannot do. “It is a continuous process of improvement,” he says.

Croma, too, began incentivising its staff based on their conduct and how they sell (such as treating the customers well, explaining the product features and not badgering them to make a sale), than on quantum of sales. “In any other retail company, four-fifths of the sales staff’s pay would be dependent on the number of sales. In Croma, 70% of their pay was decided by how they sell,” says Ghosal. To help the salesforce, brand specialists were brought in to explain the benefits of their latest launches.

Once the staff was equipped, Croma next invested in the look and ambience of their outlets. Fresh lighting was fitted in and the branding was done more prominently on the façade, enough to invite passersby inside, even if only to look. They stopped renting out the façade to brands after realising how it was blocking the entry of buyers or even window shoppers. To increase the stores’ footfall, the retailer also lowered well-thought out hooks — such as expanding their smartphone section. The store fixtures were redesigned and 40% more space was committed to the category.

To a cynical reader, all of this may simply look like salad dressing. What is so impressive about a polite salesperson and a fresh coat of paint, he or she may ask? But these came from a deeper shift in marketing strategy. Ghosal has a background in marketing and quoting Philip Kotler, the guru of the practice, he says, “Customers go through the journey of Awareness-Interest-Desire-Action in the adoption of a new behaviour or the purchase of a new product.” Product brands have to have marketing campaigns that drive the whole cycle, but retailers only have to be there for the last bit — the ‘action’ part. It essentially means a retailer like Croma does not have to convince people to buy anything, only be there when they want to and make the whole process enjoyable. This shrinks e-commerce’s menacing shadow multi-fold, and lets the retailer focus on the essential — customer experience.

Perfecting the parts

Buyers may flock to the store but a brand needs more than that. If not, what is stopping any seller from offering blinding discounts? A brand also needs to consider profitability of outlets and expansion. Croma has become ruthless with this. Ghosal indicates that the chain tracks store-level profitability on a monthly basis and actively identifies outlets that are unprofitable and are unlikely to turn profitable. “In the last four years, we have shut down numerous stores (4,000-5,000 sq ft) and replaced them with larger stores (9,000-10,000 sq ft) in the same catchment. In our assessment, Croma has always identified great catchments but not always found the right store sizes to serve those catchments,” he says.

The retailer has kept a few small format stores of 1,000-2,000 sq ft, called Croma Zip, in airports and stocks largely high-volume products such as smartphones, accessories and bags. These sell 1,000 SKUs a month. “We have had great success with the Zip format in airports but, with neighbourhood stores, we are still trying to find the right model,” Ghosal says. “Small stores are a tricky proposition in India. Given the imperfections in the real-estate market, rentals in neighbourhood markets tend to be unviable for our category,” he adds.

Croma is now also experimenting with the franchise model. For 12 years, the brand has been run as a centrally-owned and managed chain. But recently, it opened its first franchisee-owned store in Vapi, Gujarat. Bisen of Technopak says it is a sensible step. “Since 65% of the electronic retail is still happening through traditional retail, franchising allows you to tap into the psyche of a consumer who is still going to some mom-and-pop store to buy, where the pre- and post-sales support may be broken. You can improve that by giving the Croma promise,” he says. Ghosal agrees that this model incorporates much-needed local insight. It gets you good real estate and helps you expand into smaller towns, which is what Croma is planning for. “We are currently on an aggressive expansion drive,” says Mitra, adding, “This is the life-blood of all retailers and we intend to cover as many catchments as quickly as possible.”

But what about the shopper experience that Croma has invested so much in and so painfully rebuilt? He says they have a safeguard in place. “Our franchise model will be franchise owned-company operated, that is, the staff in the store will continue to be ours,” he shares. The revenue will be shared between the brand and the franchisee. Although Croma is yet to start prospecting for franchisees actively, it is already seeing interest from landlords who have partnered with the Tatas for brands such as Westside and Tata Motors.

Besides the quasi-franchise model that Croma has integrated, another buzzing model in the sector is ‘omni-channel’ retailing. Still finding its feet, it is a hybrid store format where an offline store also sells online, and vice versa. Among its many avatars, omni-channel also appears as ‘endless aisles’. If you are picturing a Matrix-style, horizonless reality — you’ve got the idea right. But its implementation is far clunkier. For this to work well, the retailer or brand must have the ability to deliver merchandise across its stores to anywhere the customer is located, and the ability to show all the merchandise on its website. The first is not always possible and the second is usually poorly executed.

While Croma, too, has an endless aisle, which accounts for over 10% of the stores’ business in home appliances, Ghosal admits that Croma’s online experience is still inelegant and not what a digitally-savvy shopper would appreciate. For his brand, he says, “retail magic” still happens in physical stores, where one would find added opportunities of upselling, offering EMIs and so on. But, it is critical for them to be present online because that is where window-shopping takes place (See: Omni-channelling).

Despite its best efforts, Croma won’t have it easy, says Rajat Wahi, partner at Deloitte India. Many categories are going to continue to grow online, he says, especially electronics, apparel, household products, books and others that do not have a wide offline distribution. Electronics, including smartphones, already account for 45-49% of the total e-commerce market. “Some categories that have wide offline distribution, such as food and FMCG, will continue to have a stronger offline footprint,” he says.

Gupta of Vijay Sales likes to see the good that the online sellers have brought, even if unintentionally. “Frankly, with a massive amount of marketing, e-retailers have also helped the market grow, specifically in the category of LED TVs. The replacement period was eight years earlier, now it is four,” he says. Gupta says he has learnt to co-exist with e-players through clever means. He noticed that re- tail websites did not give discounts on everything every day. Therefore, Vijay Sales decided to offer discounts on particular products on days when it wasn’t being offered online. It is not much of a plan, but it can keep the wolf away from the door for a while.

Mitra, too, relies on Croma’s ability to adapt, but for the long term. “We follow an omni-channel, lean working-capital and service-oriented business model that is designed to enable agility,” he says. Ghosal does not vehemently defend the brand’s resilience, but thinks it sufficient to simply quote its achievements so far as proof. “Our retail conversion (proportion of footfall at a store to those who make a purchase) has grown every year, resulting in the reversal of a Rs.2 billion loss to a Rs.2 billion profit in four years. I will leave you to compare this performance with that of the e-commerce marketplace over the same period,” he says. If that does not have the ring of confidence, we don’t know what has.