The world has transformed beyond imagination over the past few decades. Man has achieved unthinkable feats — from self-driving cars and 3D printing a two-storeyed building to gene editing and augmented reality. But despite much progress, we are still defeated by our very own bodies. Particularly, uncontrollably and abnormally multiplying cells, what we call cancer. In 2018 alone, breast cancer — the second most common variant — claimed over 87,000 lives.

Geetha Manjunath, a computer scientist from IISc, Bengaluru, suffered the loss of a close cousin to breast cancer in 2013. The shock of it led her to hunting for solutions and eventually founding Niramai, short for Non-Invasive Risk Assessment with Machine Intelligence — a company that has developed tech to detect breast cancer. There are detection technologies already, such as mammograms, but those radars were not catching every blip.

Young tech

Manjunath tells us that over 50% of the women diagnosed with breast cancer are below the age of 50, but mammography, or simply put, an x-ray scan of a breast, gives accurate results only for women above 40-45 years of age. That’s where the trouble starts.

In younger patients, the tissue density in the breast is high, and the fibroglands are more densely packed. Dense tissue shows up as white sections in a mammogram and cancerous tissue is difficult to spot through that. Manjunath’s cousin wasn’t even 40 years old when she succumbed to the disease. Hence, she was determined to figure out a solution, and she roped in Nidhi Mathur, an IIM-B alumnus and her former colleague at HP. In July 2016, they opened Niramai.

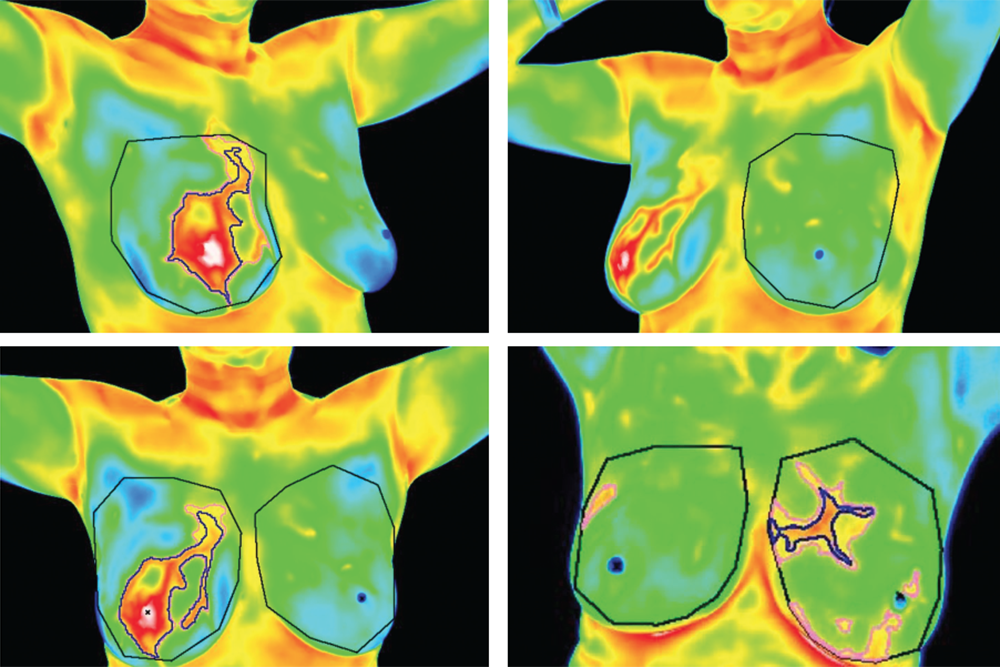

“We wanted to do something that doesn’t involve x-rays,” says Manjunath when she explains why they decided to test thermography. This method maps a patient’s body based on the amount of heat emanating from different parts. Now, cancer cells are expected to have a higher temperature than regular tissue since they consume more energy. And as your body tries to fight the inflammation-like condition that these cells create, the blood flow surrounding those tissues also increases. As a result, a cancerous region lights up in a thermal scan, right from the time a tumour invisible from the outside begins to form inside the body.

Unlike a mammogram, thermal imaging works particularly well with younger women since higher density breast tissue is better at conducting heat from a cancerous region. While thermal imaging is not unique to Niramai, Manjunath’s expertise with tech and IoT from her earlier experience at HP and Xerox gives her company an edge. The start-up uses AI to map colder regions of the body, which is useful in detecting tumours embedded deeper in the body.

This method puts to rest another concern many patients and doctors may have — radiation. Since mammography uses radiation to detect cancerous tissue, the process itself can be cancer causing. The higher the frequency of the x-rays, the higher is the probability of developing the condition. Therefore, the medical community enforces a two-year gap between consecutive tests. Meanwhile, thermal imaging does not emit any radiation.

Third, one of the biggest benefits of Niramai’s tech is affordability. At Rs.3,500 per test, mammography isn’t cheap — the machine itself costs Rs.10 million, and cannot be used for running any other scans. As a result, unless it’s a cancer-specialty hospital such as HealthCare Global (HCG) in Bengaluru, not many medical facilities want to invest in it. It’s especially hard to find one in diagnostic clinics. Meanwhile, thermal imaging costs only around Rs.1,500 per test at a city hospital. The equipment itself costs just Rs.800,000.

Next, what Niramai offers its users is simplicity and accessibility. All they need is a thermal imaging camera, a camera tripod and a computer running Niramai’s AI-based programme into which the scans are fed. A patient has to enter a room or a makeshift booth, stand bare-chested in front of the camera and change positions as instructed by the technician processing images outside on a screen. It’s completely non-invasive, whereas a mammography involves the breast being compressed between two plates, which is also painful.

Manjunath describes Niramai’s scanning process as similar to the changing room experience in a mall. “There’s no one watching or touching you because it’s a closed-door process. That way, women are comfortable during the scans,” she says. The AI algorithm processes the scans and within 20 minutes, the patient can walk out of the clinic with the report.

Heat of the moment

It may sound like the perfect diagnostics solution, but Manjunath herself admits that the method has its shortcomings. A hot-spot (red flag for a tumour) can show up on the scan because of tight clothes, hormonal changes, or even menstrual cycles. In other words, chances of a false-positive are high. But Niramai through its in-house software Thermalytix is trying to rectify that as much as possible. It takes data from thermal scans and looks for patterns and signs of breast cancer, which include rapid change in temperature gradients from one body part to the other, and asymmetric heat signatures from the body. To avoid missing a tumour seated deeper in the chest, the software even runs a warm-spot analysis. This way, cancerous tissue can be detected even if it isn’t within the breast. So far, Niramai has completed 27,000 screenings, refining the algorithm with each screening.

Another challenge the company faces is acceptance in the Indian medical industry. “In India, there is a mindset that we need approval from the US before accepting new technology,” says Manjunath. The company presents all its studies only in international publications.

Despite their efforts, there are sceptics such as Dr Anthony Pais, oncoplastic breast surgeon, co-founder and clinical director, Cytecare, Bengaluru. He goes as far to say that thermography-based screening technology is a money-making scam and adds, “It’s ideal for commercial hospitals and a gateway to bring patients to take up a mammography test.”

His distrust comes from the high percentage of false positives he saw when he tested another thermography-based service, iBreast. He adds that it is not an approved technique in the US. To counter this perception block, Niramai has filed for approvals from the USFDA.

According to one of Niramai’s clients, Dr Ajai Kumar, oncologist, chairman and CEO, HCG, “The FDA approval is among the last hurdles for Niramai, and is a matter of time.” He adds that the start-up’s tech has seen positive response at his hospital in its pilot phase, and the two parties are currently negotiating pricing to make the service commercial.

Dr Sudhakar Sampangi, radiologist at HCG explains the two sides of the coin. “A false positive is the main weakness in the case of thermography, but in the case of mammography, it’s false negatives,” he says and elaborates with an example. A 42-year-old woman came to HCG for a mammography test, which returned a negative. Niramai’s thermal imaging scan showed that she was a borderline case. Later, the ultrasound confirmed that by detecting she had early-stage breast cancer. Sampangi says that mammography is 60-70% accurate at detecting lesions, thermal imaging up to 85%, and ultrasound 85-90%, but points out that thermal imaging is poor at detecting tumours around the ribcage.

The big C

Hospitals such as HCG and other diagnostic centres contribute to Niramai’s primary revenue model. Here, the start-up provides an end-to-end solution and all that the hospital needs to provide is a room. The hardware, installation and connection with Niramai’s cloud-servers, and staff-training are handled by Manjunath’s team. It’s a one-day, plug-and-play process and for this, they have built a subscription-plus-revenue-share model. There is also an upfront cost since the hardware is imported and not manufactured by Niramai. Currently, this is the sole source of the start-up’s revenue.

The secondary model mostly functions as a CSR operation. In this, in-house trained technicians go to corporate houses, villages and apartment complexes to conduct screenings. In 2019, Niramai conducted its screening tests at all government hospitals in Bengaluru. Such projects are volume drivers and help train the start-up’s AI algorithm, but such screening is manpower intensive. Hence, the team controls the frequency of such projects. But Manjunath is hoping to work with several state governments and hospitals to make this model successful. In fact, Bengaluru-based Sakra World Hospital even has a bus called the ‘Pink Express’, in which they have installed Niramai’s tech to spread awareness about breast cancer.

Reenita Das, partner, Frost & Sullivan, believes that Niramai is forming the right partnerships to increase scalability. That said, she adds, “The challenge now will be to improve scalability and enter global markets.” The other major draw for these tests is the price-point; group tests cost about Rs.500/patient and almost nothing when it comes to charging patients in villages. “Niramai provides patients convenience, accessibility and hopefully, affordability in the long term,” adds Das. The company is working on corporate sponsorships to support this model, but has been mostly absorbing the cost of these tests for now, thanks to the $7 million fundraising from Axilor Ventures, pi Ventures, Binny Bansal, and Dream Incubator — the Japan-based VC. Manjunath believes the initial funding is likely to sustain the firm for another two years, which is around the time she also expects the business to break even.

Niramai got its start at Axilor’s 2017 accelerator programme and has been among the more successful ventures in its portfolio. Prachi Sinha, head of healthcare investments, Axilor Ventures, says, “Healthcare has been one of our focus areas and Kris Gopalakrishnan (chairman) has supported ventures that have a strong background in research and academia.” Naturally, Niramai made an interesting investing opportunity for Axilor. “The company came to us when we were on the lookout for start-ups with a strong biotech angle,” she says, adding that Niramai has the potential to create a 50-100x impact in terms of cost and accessibility to breast cancer diagnosis.

Since the venture involved both healthcare and AI, Sinha and team knew that uptake would be slow and making key opinion leaders aware of the technology would be crucial. That’s why they roped in Biocon’s Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw on to its board, who plays mentor to the team. Connecting Niramai to HCG and Bengaluru’s Narayana Hrudayalaya also helped Manjunath build base for clinical trials.

Another investor, Manish Singhal, founding partner, pi Ventures is betting big on Niramai because “it addresses a large supply and demand gap”. He says, “AI can mimic trained human health professionals. If the machine can be made to learn from high-quality sources (doctors), services such as Niramai can provide access to diagnostic services to a large target audience. There isn’t even the need for a trained nurse here.”

Going forward, Manjunath and team plan to focus on thermalytics. “Ours is a unique proposition and it’s an area we have managed to crack. We’ll try to consolidate and capitalise on our expertise for now,” she says. Regarding the role of technology in cancer treatment, she considers the world’s population as part of a continuum. Niramai’s AI will improve over time, thanks to the data from all the scans and from breast cancer survivors. It could finally change the odds in favour of human life.